Arthur Conan Doyle and the Adventure of the Boer War

Eight years after giving up medicine for writing, the internationally famous creator of Sherlock Holmes became Dr Doyle once more, on the front line of the Boer War.

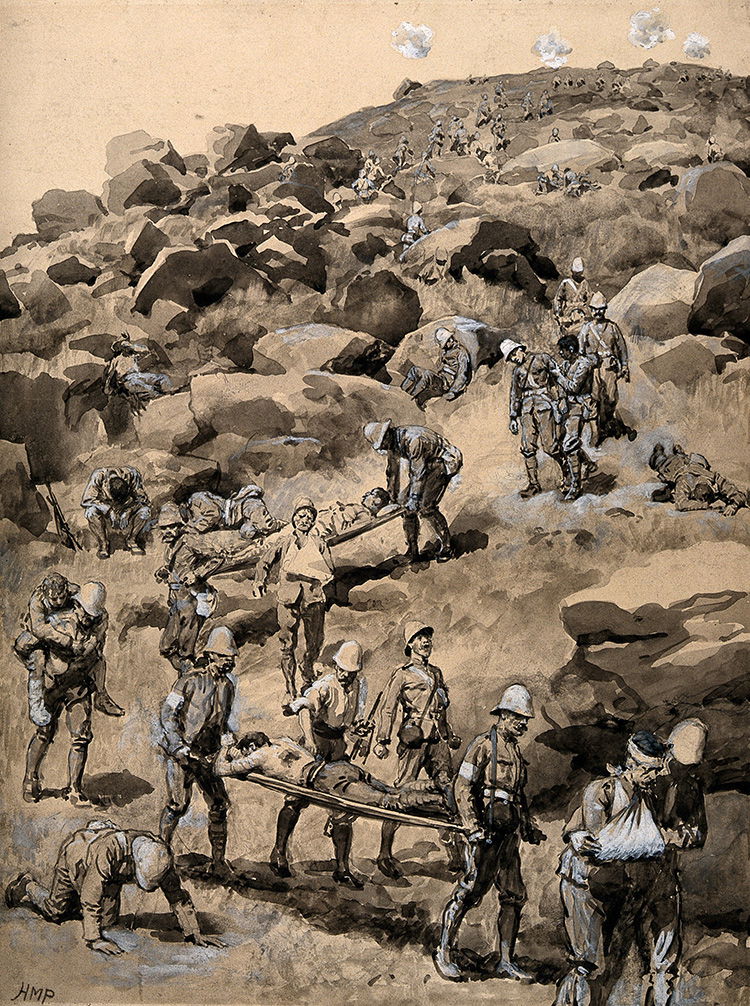

Treating and looking for the wounded at the battlefield during the Boer War, print after F. Craig, c.1900.

In May 1899, five months before war was declared between Britain and the two Boer Republics of South Africa, Arthur Conan Doyle turned 40. He was a big man, six feet tall and tipping the scales at 16 stone, with fair hair and a long upper lip on which he cultivated a luxuriant moustache that he combed to either side in what was known as the ‘English’ style. The epitome of the sporting type, he played cricket in the summer, football in the autumn and, in the spring, holidayed in Switzerland, where he was one of the first British tourists to strap on a pair of wooden Norwegian skis. Doyle had trained and practised as a doctor until the success of his Sherlock Holmes stories allowed him to give up medicine and become a full-time writer. He was a great admirer of Sir Walter Scott’s historical novels and he hoped that his own historical novels would form the basis of his literary reputation, along with his histories of the Boer War and the First World War.

The outbreak of war between Britain and the Boer Republics on 13 October 1899 was the culmination of a long campaign of warmongering in Cape Town by Cecil Rhodes – former prime minister of Cape Colony – and the British High Commissioner Sir Alfred Milner. Their motives were commercial – control of the gold mines in the Transvaal – and also political. Rhodes especially nurtured a grand imperialist vision that embraced the whole of Africa. However, the excuse they used for promoting war against the Boers was the position of the uitlanders – foreigners drawn to the Transvaal by the gold deposits on the Witwatersrand – who were denied the vote by the Boer government. Back in Britain, the Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain offered a sympathetic ear to the arguments put forward by Milner and Rhodes.

Conan Doyle believed passionately that in this quarrel with the Boers the uitlanders – many of them Englishmen or Scots – were the underdogs. Not everyone in Britain agreed with his analysis: his own mother Mary Doyle was far from alone in seeing the outbreak of war as an act of aggression by a greedy imperial power against two much smaller nations.

Both Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling (soon also to leave for South Africa and the arena of war) were keen for Britain to call on volunteers, to match the colonial troops from Australia, Canada and New Zealand that both men greatly admired. Doyle wrote to the Times: ‘Great Britain is full of men who can ride and shoot … it only needs a brave man and a modern rifle to make a soldier.’ He volunteered for the Imperial Yeomanry, but was turned down, possibly because of his age, possibly because of his size, most likely a combination of the two. Having volunteered, as he was ‘honour-bound’ to do after his letter to the Times, and having had his offer turned down, he was worried that walking along the street he would bump into this or that person who would greet him with a surprised, ‘Hello, Doyle, I thought you were at the front.’

If the British army refused to accept him as a soldier, however, they could hardly refuse him as a medical man: by December it was clear that the recently formed Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) was struggling to cope with the huge number of casualties. Hearing that a friend of his, John Langman, was staffing and equipping a private field hospital to be rushed out to South Africa, Doyle volunteered his services. Thus, eight years after he had given up medicine for writing, Arthur Conan Doyle, internationally famous creator of Sherlock Holmes, became once more Dr Doyle, physician to Langman’s Field Hospital.

On 28 February 1900 the 50 hospital staff gathered in the pouring rain on the Royal Albert Dock at Woolwich to board a converted P&O freighter, the SS Oriental. Once they were out at sea Doyle was one of the first to put himself forward for the newly developed inoculation against typhoid (commonly known as enteric fever). The correct dose was yet to be determined. The inoculation made Doyle feel ‘mighty sorry’ for himself, but he recovered sooner than many of the others and by the time the Oriental reached the Cape Verde Islands he was fit enough to play in the ship’s cricket team. He was also spending time writing the opening chapters of his history The Great Boer War. He was sanguine he could get it out in time for the end of the war, which he believed – as did most of the British public – would be within a matter of months.

On 28 March they disembarked at the port of East London and travelled for Bloemfontein, the capital of the Boer Republic of the Orange Free State, which had fallen to British forces under Commander-in-Chief Lord Roberts only ten days earlier. Bloemfontein lay 350 miles to the north, a journey that took four days and nights on a single-track railway line. They arrived just in time to deal with the catastrophic consequences of the Battle of Sanna’s Post, when two groups of Boer commandos had ambushed a large British column, stealing a number of the heavy guns and leaving hundreds of casualties. More significantly, the Boers had seized control of the waterworks that provided the town with clean water. Desperately thirsty men were now drinking contaminated water from old abandoned wells and from the River Modder.

Within days the Langman hospital tents, erected on the cricket pitch of the Ramblers Club in the centre of Bloemfontein, were filling with cases of typhoid. ‘The outbreak was a terrible one’, wrote Conan Doyle, ‘we lived in the midst of death – and death in its vilest and filthiest form.’ At the beginning of the third week in April violent thunderstorms broke over the town. The tents stood in a swamp of mud and faeces. Doyle and his colleagues gave out their address as Café Enterique, Boulevard des Microbes. In Kipling’s poem ‘The Parting of the Columns’ the Tommies refer to the town as ‘Bloeming-typhoidtein’.

By the end of the war, when the Treaty of Vereeniging was signed in May 1902, 22,000 British and colonial troops had lost their lives. Over half of those died of disease, mainly typhoid. Conan Doyle had left South Africa in July 1900, when the front moved from Bloemfontein to Johannesburg and then Pretoria. The fall of Pretoria, the capital of the Boer Republic of the Transvaal, led to increased guerrilla activity on the part of the Boer commandos. The British responded with a ‘scorched earth’ policy, ordered by Lord Roberts and implemented by Lord Kitchener of Khartoum: they burned the Boer farms, killed the livestock, destroyed the crops and gathered up the women and children into concentration camps. Over 22,000 Boer children died in the camps, of starvation, typhoid and measles. There is no accurate figure for the mortality rate in the camps where the black population was concentrated: the 14,000 recorded deaths are considered a gross underestimation. There, too, starvation and typhoid were the killers.

Conan Doyle thought that in South Africa his own life had probably been saved by his anti-typhoid inoculation. On his return he campaigned for mandatory inoculation for all the armed forces, along with other preventive health measures such as the boiling of drinking water; he campaigned for rubber life belts for sailors in the Royal Navy (most of whom couldn’t swim) and for inflatable lifeboats for the ships they sailed in.

But he remained stubborn against any imputation that the British in South Africa had ever behaved less than honourably, a position he shared, again, with Rudyard Kipling. As details of the horrors of the concentration camps were brought back to Britain by campaigners such as Emily Hobhouse (loathed by Kitchener, vilified in the press), so public questioning grew. Journalist W.T. Stead, Doyle’s one-time friend (they shared an interest in spiritualism) but now bitter political opponent, published The War in South Africa: Methods of Barbarism, which detailed British atrocities. Doyle’s The Great Boer War, a lively but partisan and necessarily interim military account, had already been published. Now, incensed by what he perceived as scurrilous anti-patriotic propaganda, Doyle published his own The War in South Africa: Its Cause and Conduct, which refuted the claims of Hobhouse and Stead. Just as he had taken on the cause of the uitlanders, so now he took on the cause of the traduced British soldier in South Africa. Burning farms? What burning farms? Looting and rape? What looting and rape? He wanted to show the world the British Tommy as he had known him – briefly – in Langman’s Field Hospital in Bloemfontein: stoical in the face of fever, disease and death.

Over the years other causes and other underdogs would catch Conan Doyle’s imagination. One was the case of George Edalji, son of an English mother and Indian father, who had been found guilty on no evidence of a series of attacks on horses in the area of Staffordshire where the family lived. Edalji was sentenced to a long period of imprisonment with hard labour. Doyle wrote thousands if not hundreds of thousands of words on his behalf and eventually proved Edalji’s innocence. He came to the conclusion that the young man was a victim of what we would now call institutional racism, writing: ‘The sad fact is that officialdom in England stands solid together.’ Two years later, in 1909, he put his considerable literary skills at the service of E. D. Morel’s Congo Reform Association, drawing on evidence provided by ex-diplomat Roger Casement of the atrocities being perpetrated by the regime of King Leopold of Belgium against the people of the Congo. His The Crime of the Congo was influential in alerting not just the public but also parliamentarians to the slave state that was the Congo. (Mark Twain was another writer to take up the cause with his satirical King Leopold’s Soliloquy: A Defense of His Congo Rule.)

In 1914, 15 years older and a stone or two heavier than he had been at the outbreak of the South African War, Conan Doyle (now Sir Arthur) volunteered once again and was accepted as a private with the Crowborough Company of the Sixth Royal Volunteer Regiment. His duties included supervising the work of German POWs on local farms. But he soon managed to get himself sent as a Foreign Office observer to the various front lines in Europe, where he gathered information for yet another history of an ongoing war. The British Campaign in France and Flanders was published in six volumes; it was as partisan as his history of the Boer War but lacked its liveliness. He later reflected sadly that it ‘has never come into its own’. Doyle is not now remembered for his military histories, nor for his historical novels (delightful though some of them are), nor for his important campaigns for the modernisation of disease prevention, but rather for an achievement he never rated very highly: the creation of Sherlock Holmes.

Sarah LeFanu is the author of Something of Themselves: Kipling, Kingsley, Conan Doyle and the Anglo-Boer War (Hurst, 2020).