‘Backbone of the Nation’ by Robert Gildea review

Backbone of the Nation: Mining Communities and the Great Strike of 1984-85 by Robert Gildea is shaped more by heartbreak than heroism.

In the UK, May and June 2022 were officially a ‘hot strike summer’, in which the context of the country’s cost of living crisis generated popular support for workers’ action and admiration for plain-speaking union leaders such as the RMT’s Mick Lynch. The whole thing seemed underpinned by a certain nostalgia, not least bringing to mind that other ‘hot strike summer’ of 1984.

In his introduction, Robert Gildea notes the resonance of Lynch’s rhetoric as a reason to pay the strike renewed attention. He also acknowledges the breadth of scholarship on the strike, both contemporary reportage and memoirs and more recent explorations: Seumas Milne (1994) on the involvement of state intelligence services, Diarmaid Kelliher (2021) on the cultural links developed between London and the coalfields, and Huw Beynon and Ray Hudson (2021) on the strike’s bleak legacy. All of which might cause us to ask not whether we should now pay attention to the Miners’ Strike, but whether we have paid enough already.

What Backbone of the Nation offers, however, is the first comprehensive oral history of the strike based on new interviews supplemented with archived testimony from across Wales, England and Scotland. It has a cast of ordinary characters (some, like MP and scholar Hywel Francis and activist Anne Scargill, are better known than others) and its objective overview extends to the miners of Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire as well as the rock-solid strongholds of Yorkshire and south Wales.

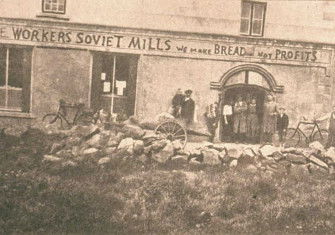

The book’s title is reflected in the opening outline of coal mining’s development in Britain. From our post-industrial perspective, the story is overshadowed by the knowledge of impending disaster, but mining communities at the time of the strike had also glimpsed what was coming. Siân James, whose journey from miner’s wife and activist to MP formed part of the 2014 film Pride, recalls that 1984 had ‘the inevitability of a train wreck’.

Gildea is clear that, although demand for coal had been in decline for decades before Thatcher, the 1984-85 strike was a deliberate act. The intricacies of internal ballots, picketing strategies and tactical divisions across different regions of the coalfield – keenly debated here by contributors – were secondary to the overall desire for a titanic clash of people and state. In preparation, the government stockpiled coal, appointed the hawkish Ian MacGregor as National Coal Board chairman, and drew up a list of colliery closures that would decimate the industry. On the other side, Gildea records an uncompromising generation of young miners, often Marx-reading students of industrial relations, economics and politics, intent on shaking up their union’s staid bureaucracy.

The book’s sober narrative doesn’t avoid this sense of high-stakes combat, as contributors recount defending their jobs and communities against a backdrop of invasion, occupation and state violence: the guerilla tactics of flying pickets, mounted police charges through mining villages, the pitched battle at Orgreave, and the arrests and show-trials of strikers on trumped-up charges. Doncaster miner, activist and author Dave Douglass draws comparisons with Northern Ireland, while Lyn Harper of Blaenant states bluntly: ‘We were at war.’

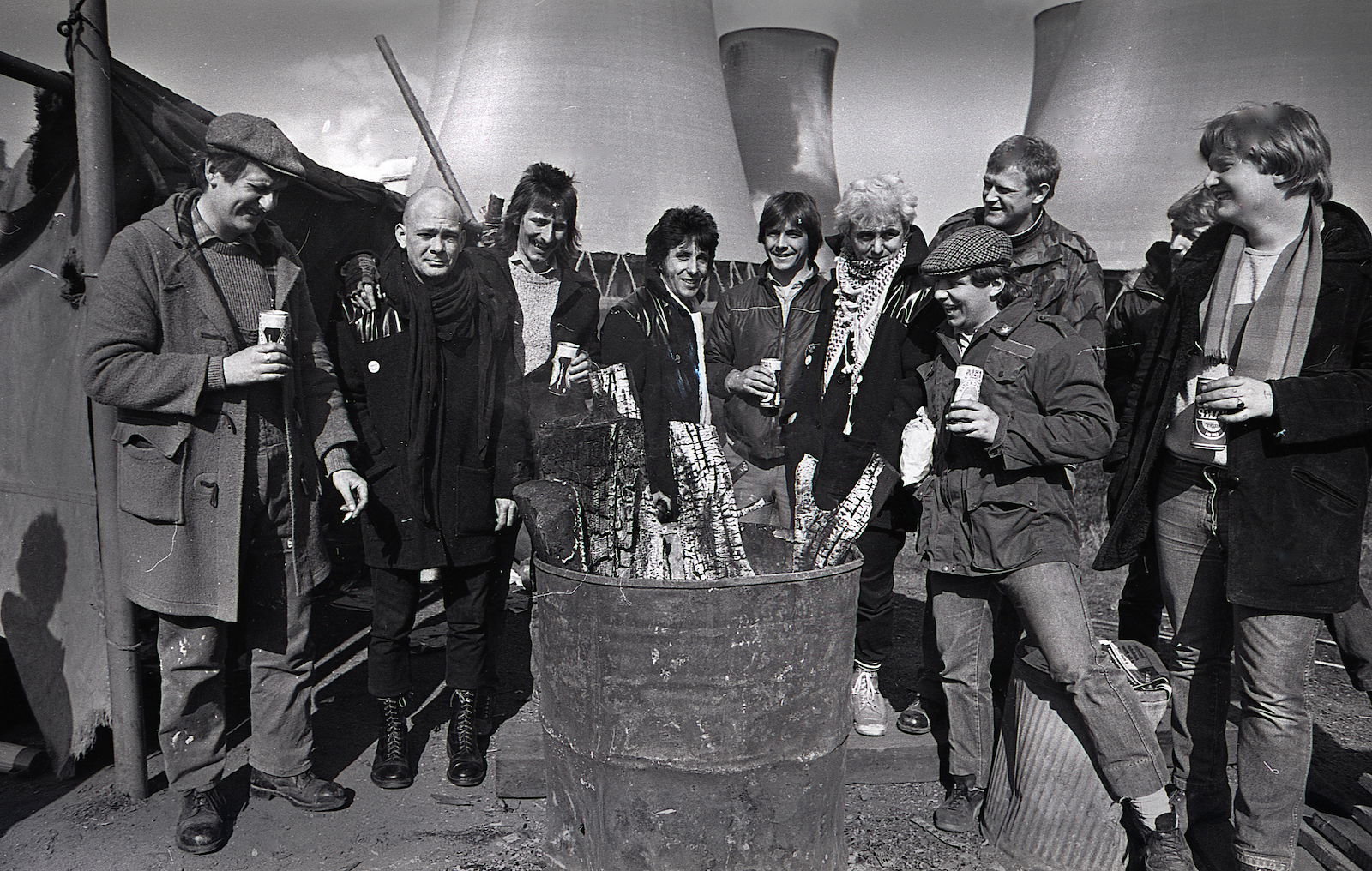

While there are nods to high-level political machinations, and to the wider neoliberal project that Thatcherism represented, the book’s focus is on the personal experience of those on the frontline. Men and women offer picaresque accounts of picketing, evading or clashing with police and, later, as the harsh conditions of life on strike set in, of setting up and running soup kitchens, support groups and fundraising tours across Britain and beyond. The interviews usefully bring out the often submerged interpersonal and political tensions among the various solidarity groups, the National Union of Mineworkers’ executive bodies and its rank and file, as well as between mining communities and their middle-class supporters. Allyship from other workers was less complex and more strategic – some, like Fleet Street’s printworkers, saw clearly that a defeat of the miners would mean their jobs would be next. For many, the strike became an education in politics and the power of the state.

The book’s wealth of anecdotes, with exhaustive accounts of struggle and sacrifice, give an immersive effect. Contributors switch between resigned fatalism, ironic or bitter amusement, and an enduring disbelief at the violence, injustice and lies levelled against them. By the start of 1985, with the strike in its 11th month, miners had starved through Christmas and been reduced to scavenging coal from local slag heaps, but the NUM, coalfield communities and even families remained split over whether to extend or end the strike. At its eventual conclusion two months later, the epic scale of both the event and the emotions involved is captured by Yorkshire miner’s wife Dianne Hogg, who likens the return to work to ‘a movie where the heroine dies and all you want to do is sit and cry’.

After these closing credits, the story continued: returning strikers were victimised, sacked or blacklisted, former scabs were ostracised, while the government turned its guns on other unionised industries. Like other places where identity was built on labour, mining communities fractured as established industries were replaced – if at all – with insecure, low-skilled and low-wage jobs. But many continued on the path of political activism the strike had opened up, or opted for a new start in education, local heritage, social work or community care – where they often dealt with the onslaught of poverty, drug and alcohol use and depression that swept the coalfields in the strike’s aftermath. A final chapter examines how the strike’s economic and emotional repercussions still affect younger generations, but also how its legacy is not just one of defeat but of lasting connections and ongoing solidarity with justice campaigns from Hillsborough to Grenfell Tower.

Shaped more by heartbreak than heroism, Backbone of the Nation is a rich and valuable record, if an unavoidably painful read.

Backbone of the Nation: Mining Communities and the Great Strike of 1984-85

Robert Gildea

Yale University Press, 496pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Rhian E. Jones writes on history and politics.