Belarus Begins Again

Belarus’ history has been a series of false starts, but the recent uprisings against Alexander Lukashenko suggest a new chapter is imminent.

Victory Square, Minsk, 1981.

Belarus has been an independent state since the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, though largely by default. Unlike other Soviet Republics, there was no grand Declaration of Independence or popular referendum. An earlier sovereignty law was upgraded after the failed Moscow coup against Mikhail Gorbachev in August 1991, followed by a name change in September from the ‘Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic’ to the ‘Republic of Belarus’. Independence Day is celebrated on 3 July, the date of the liberation of Minsk from German occupation in 1944.

Belarus has been run by would-be president for life Alexander Lukashenko since 1994. He has centralised power, marginalised all opposition and ‘won’ rigged elections on no less than four previous occasions. The events of 2020 have caught almost everybody by surprise: a stage-managed election campaign was suddenly gate-crashed in May by a real opposition. Lukashenko ignored it and declared his usual 80 per cent plus victory, provoking the biggest protests in Belarusian history. (A parallel vote count showed that Lukashenko won only 40.5 per cent and the opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya 47.9 per cent). Lukashenko resorted to brutal suppression and asked for Russia’s help. Even if he survives, his power now rests on coercion alone.

Much of what has happened was caused by sudden sparks and by Lukashenko’s mistakes. But there are long-term trends that are dissolving old stereotypes about Belarus. It is often ignored because it is somehow not a ‘real’ country; or diminished because it is pro-Russian; or, to use Friedrich Engels’ meaningless cliché, Belarusians are considered a ‘non-historical people’. But all peoples have a history. Belarus’ problem is that its history has been a series of false starts. Now it is beginning its history again.

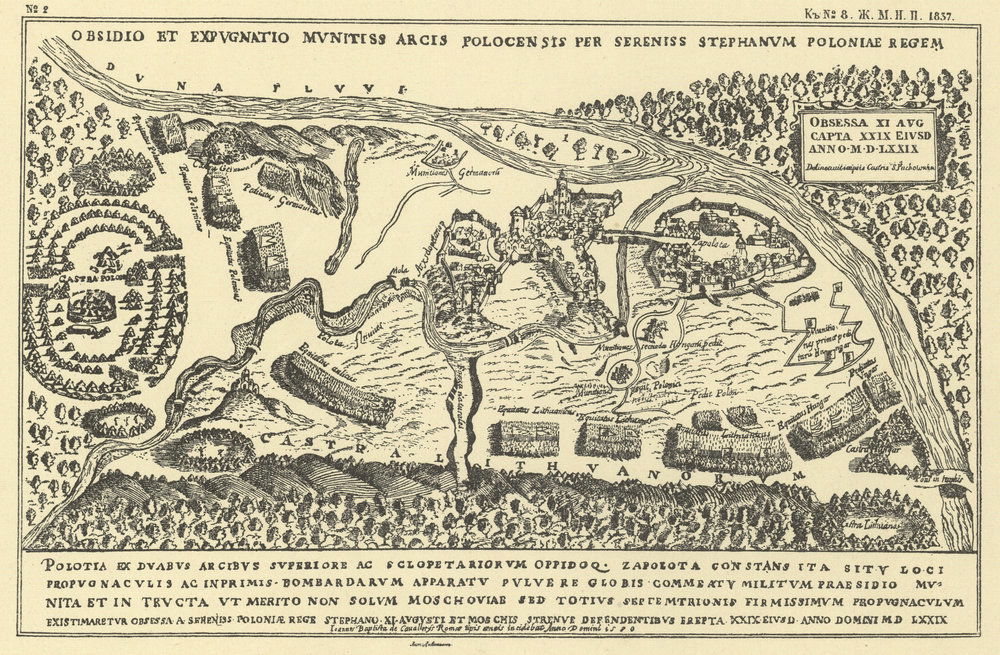

Belarus began life as part of the early medieval state of Rus’, which existed from the ninth to the 13th century. Rus’ was not Russia (the modern name for Russia is Rossiya, a Hellenism introduced in the 17th century). Rus’ was not Ukraine and it was not Belarus. It was what preceded all three. But the three East Slavic peoples once shared a common home. The main Belarusian part was the principality of Polotsk, on the River Dvina (Daugava), which dominated trade with the Baltic via client cities in what is now Latvia. Many Belarusian historians place the origins of a proto-Belarusian identity in this synthesis of Balts and Slavs. Like Northumbria in the seventh and eighth centuries, Polotsk (987-1397) was sometimes semi-detached and sometimes independent of the other principalities and Kyiv, the usual centre of rule. In the 1920s, the historian Vatslaw Lastowski (1883-1938) argued that Belarusians should actually call themselves Kryvichi, the name of the Slavic tribe that founded Polotsk.

Polotsk then helped found Litva. This is an unfamiliar name in English, where we refer to the state as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. During the 15th century Litva grew to become the largest state in Europe, covering land in what is now Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, Ukraine, Poland and Russia. It was a multi-ethnic state of Lithuanians, Belarusians, Poles and Jews. Collectively, they were ‘Litvins’; local Jews called themselves ‘Litvaks’, including the artist Marc Chagall. Belarusians played a prominent role, because the Lithuanians were illiterate pagans until the 1380s. Many still thought of themselves as ‘Litvins’ until 1917. The appeal of this identity has revived in opposition circles under Lukashenko.

The majority of Belarusians belonged to the Greek Catholic Church. This Church was called the ‘peasants’ faith’, but it had a strong Baroque culture, influenced by the Jesuit order and central European notions of Magdeburg law, a legal code derived from Germanic rather than Roman traditions. Cities like Hrodna and even Minsk might look post-Soviet, but they don’t look particularly Russian. Their churches do not have many golden domes; most were originally Catholic before they were Orthodox. Litva was swallowed up by the Russian Empire in the 18th century (normally mislabelled in English as the ‘Partitions of Poland’). The empire viewed Greek Catholics as apostates and suppressed the Church from 1839. The main carrier of a separate local identity was dismantled, just as Belarusians entered the modern era as subjects of the late Imperial and Soviet identity-building projects. Belarusian historians like to tell the story of this era as one of teleological ‘national revival’, but the national movement was tiny before 1918. Belarus was also split between Roman Catholics and Orthodox. Many Catholics supported the Litvin idea and the local patriotism of the Krai (region). Many Orthodox backed ‘West-Rus-ism’, arguing for kinship with the Russians against the Poles.

A ‘Belarusian People’s Republic’ existed for a few weeks in March 1918. A national movement developed briefly in the 1920s, in what was then eastern Poland. But a traumatic 20th century wiped the slate clean again. The Holocaust killed over 800,000 Jews locally and destroyed the multi-ethnic basis of Litvinism. A quarter of the whole population perished. Belarusians have a very Soviet view of the Second World War. Unlike Ukraine or Lithuania, there was no nationalist partisan movement. The partisans were red.

Belarus won the war. Yes, you read that correctly: Belarusian resistance slowed the German advance in 1941 to ensure they failed to take Moscow. The German army in the east was decimated on Belarusian territory in Operation Bagration in the summer of 1944 – at least as big a blow as the Normandy landings. Veterans dominated the postwar leadership of the Communist Party in Belarus. Their prestige and the disappearance of the threat of invasion from the West meant high levels of Russian investment, even up to the 1980s.

Lukashenko won power in 1994 by promising to preserve the best of the Soviet system; its social contract and historical memory, and a return to peace and stability. He was able to marginalise the nationalist movement, which had been unable to displace the communist nomenklatura in 1991-4, and reshape that nomenklatura under his own authority. He was lucky: as his power consolidated in the early 2000s he was able to enjoy huge Russian subsidies of cheap oil and gas in return for his political loyalty. A so-called ‘Union State’ between the two nations has existed since 1999, which is not the meaningless entity sometimes claimed, as it guarantees free movement and employment in both states.

But this union began to break down after the war in Ukraine began in 2014. Belarus sought to protect its sovereignty; Russia demanded more in terms of friendship and was no longer willing or able to pay so many of Belarus’ bills. Lukashenko largely coasted through the 2015 election, as most of the opposition agreed not to rock the boat. But economic problems accumulated. In 2017 there were widespread protests against an ill-judged ‘parasite tax’ on the economically inactive. People began to talk of ‘two Belaruses’: the left-behind, the state economy and the regions versus the new private economy in Minsk, a booming IT sector in particular. Both groups were further alienated by Lukashenko’s minimalist response to Covid-19. Both had candidates in the 2020 election: the populist vlogger Sergei Tikhanovsky for the ‘left-behinds’ and two businessmen Valery Tsepkalo and Viktor Babariko for the new economy. Lukashenko clumsily banned all three from standing, but maladroitly allowed proxies to take their place, led by Tsikhanouski’s wife Svetlana.

As the Ukrainian journalist Nataliya Humenyuk has written, the campaign and the protests have showed the upside of Lukashenko’s neo-Soviet years. There are no divisions of identity politics, language or region: Lukashenko’s rule has homogenised Belarus. The red and white flag of 1918 and 1991-95 (Lukashenko restored a modified version of the Soviet flag) has been used as an anti-Lukashenko symbol, rather as a nationalist one. There is no party-based opposition, but that means protestors see themselves as an amorphous majority and do not have to worry that some self-interested political force will hijack the protests. The repression of parties and NGOs has ‘privatised’ civil society: subterranean networks have knitted together with a new spirit of solidarity, first awakened by the pandemic. Protests are peaceful and even polite. There is as yet no anti-Russian feeling. In Ukraine in 2013-14 people rebelled against both President Viktor Yanukovych and the Russian factor behind him. Lukashenko is not a Russian export: his rise to power in 1994 predates Vladimir Putin’s in 2000. The regime’s appalling violence means that Lukashenko can no longer play the peace and stability card.

Lukashenko wanted to be seen as father of the nation; he now mocks protestors who ‘scattered like rats’ and threatens them with his ‘cruel side’. The people have outgrown their dictator. They will now take separate paths.

Andrew Wilson is Professor of Ukrainian Studies at UCL SSEES. His book Belarus: The Last European Dictatorship will be republished in 2021 to take account of recent events.