Britain and America’s Theatrical War

In the 19th century, American theatres provided the stage for a war between high and low culture, the elite and ‘Know-Nothings’ – and Britain and the US. In 1849, events turned bloody.

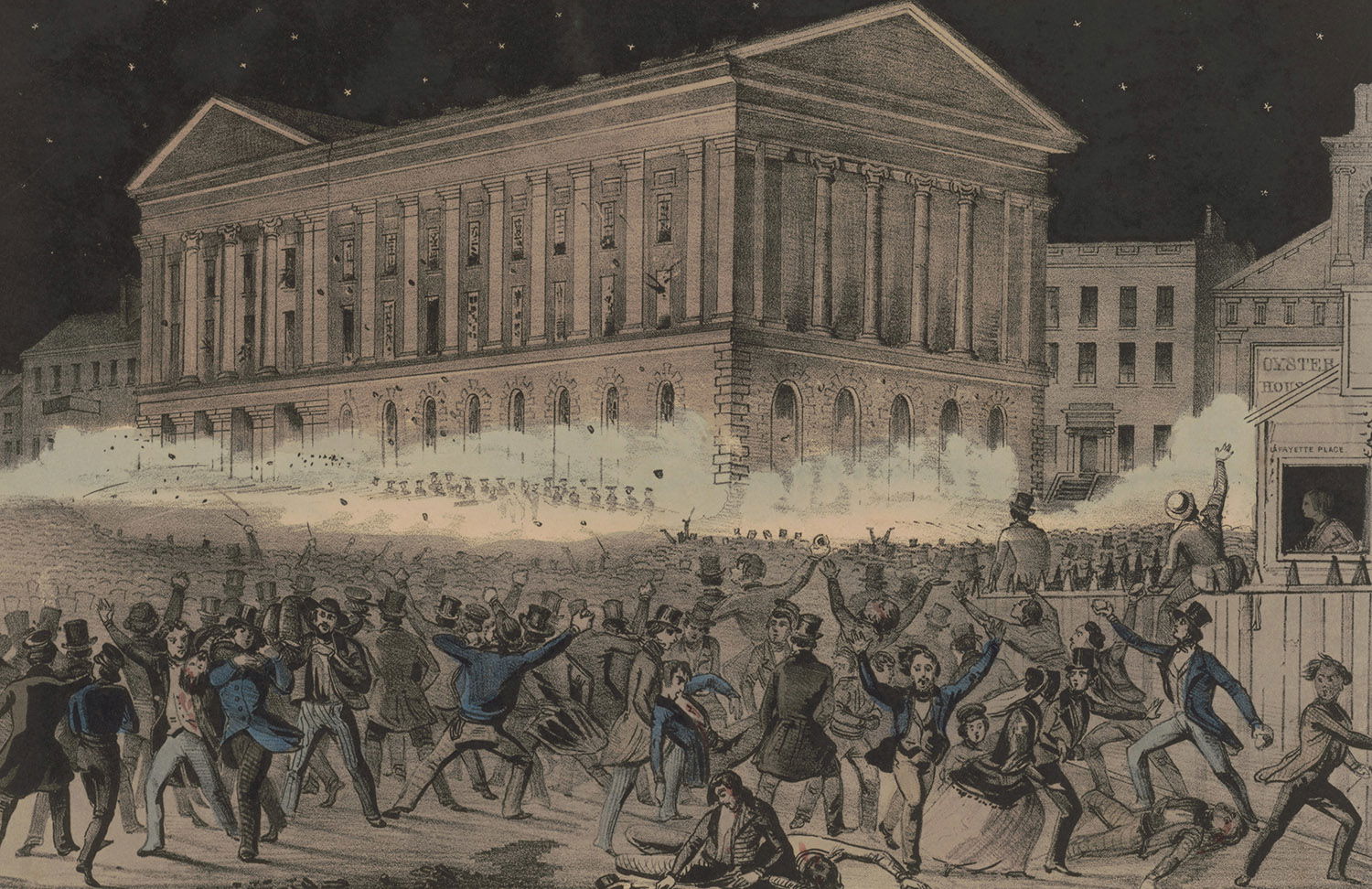

Great riot at the Astor Place Opera House, New York, on Thursday evening, May 10th 1849.

In the years before managers could dim auditorium lights and keep audiences in darkness during a performance, culture and politics met head-on in 19th century American theatres. Endowed with a conviction in their ‘natural right’ of self-expression, audiences would attack bad acting, poor plays and, more commonly, English actors. In 1821, Bostonians ended a performance by the tragedian Edmund Kean because he had refused to play Richard III for a small audience. In 1831 and 1832 rioters in New York attacked the actor Joshua Anderson, who had reportedly made anti-American remarks en route to the United States. Two years later, when New York stage manager William Farren was overheard cursing the ‘Damn Yankees’, audiences disrupted performances at his theatre until he came on stage bearing an American flag and apologised.

In each of these cases, the rioters eventually settled down, their demands satisfied. This was not the case on 10 May 1849, when the eminent British actor William Macready defied protest and took the stage at the Astor Place Opera House in New York to play Macbeth. Disturbances inside and outside the theatre grew so violent that troops fired into a crowd of rioters, killing 22 and wounding more than 100. After six months, a small number of people had been jailed. But such a calamity had been a long time coming. Unlike earlier disturbances, the ‘Astor Place Riots’, as they came to be called, almost set off a revolution.

Theatre-going in the United States in the mid-19th century more closely resembled Elizabethan than Victorian London. All classes of people attended the same theatres, co-existing in a shaky peace. The readiness to riot empowered the rough-and-tumble, self-styled ‘common man’ to rule the theatre. When an actor or manager did something to elicit their displeasure, criticism might include harsh words and chants as well as various missiles like eggs, vegetables and, on occasion, animal carcasses or furniture.

While the middle and upper classes occupied the pit and semi-private boxes, rowdy theatregoers ruled from the galleries. Typically known as ‘Bowery B’hoys’ or ‘Soaplocks’ for the copious amounts of grease they used to groom their hair, they unleashed their ire on other audience members. Writing under a pseudonym, Washington Irving, author of ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ and ‘Rip van Winkle,’ observed that, if rankled, these ‘gallery gods’ typically ‘commenced a discharge of apples, nuts & ginger-bread, on the heads of the honest folks in the pit’. His advice to theatregoers was to ‘sit down quietly and bend your back to it’.

In this raucous environment, the city’s cultural elite sought solace away from chaos. The Astor Place Opera House was built in 1847 above the crowded quarters of the city at Astor Place. Away from the centre of town in a refined neighbourhood, they hoped to create a space for European opera and English drama. Audiences who identified with the B’hoys fumed at the city’s ‘Upper Ten’ per cent who engineered the move, especially once the Opera House took the unprecedented step of excluding them by introducing a dress code. To the democratic masses, this smacked of un-American, aristocratic privilege.

.jpg)

Yet while many Americans perceived British culture as snobbish and elitist, the country embraced Shakespeare as one of their own. In the decades before 1850, Shakespeare was the most performed playwright in the United States. James Fennimore Cooper, author of Last of the Mohicans, wrote – without irony – that Shakespeare was ‘the great author of America’. The French writer Alexis de Tocqueville marvelled in his travelogue Democracy in America (1835) that no matter where he was, ‘there is hardly a pioneer’s hut which does not contain a few odd volumes of Shakespeare’.

One individual who embodied this cultural contradiction was Shakespearean actor Junius Brutus Booth, father of Abraham Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth. Booth was born and raised in London; however, because he paid homage to American audiences, praising and pandering to their patriotic fervour, they lauded him as one of their own. On Evacuation Day in 1832 – a local holiday commemorating British troops’ withdrawal from New York in 1793 – audiences at the working-class Bowery Theatre took to the stage during the final scenes of Richard III to make sure that Booth’s Richard and had a ‘fair fight’ with Richmond that lasted almost 30 minutes.

By contrast, Macready held such audiences in contempt. Writing in his diary, he referred to American actors as ‘barbarians’, whose acting would make a ‘dog vomit’. When he performed Macbeth in 1849 for an elite audience in Astor Place, popular opinion in the city was that the show was a theft of ‘American’ culture.

While Macready appealed to cultured New Yorkers who wanted to escape garish behaviour, his American rival, Edwin Forrest, was a champion of patriotic, working-class B’hoys. Where Macready was gentlemanly and cultured, Forrest was coarse and raw. Macready was known for his refined technique, Forrest for his robust athleticism. The first American-born star, Forrest was an ever-present thorn in Macready’s side.

The feud began in 1846 when Forrest saw Macready perform Hamlet in Edinburgh. Macready’s performance included a signature manoeuvre. Delivering the lines ‘They are coming to the play: I must be idle’, he executed a pirouette and flicked his handkerchief in a flourish. Forrest, who found this bit of staging effeminate, did the unimaginable: he hissed. While in London there was shock that the great Macready had been publicly insulted, Forrest published a letter in The Times admitting to the attack. He railed against the ‘fancy dance’ that he said was a ‘desecration of the scene’ and concluded by attesting to his God-given right to express disapproval, much like typical American audiences of the time. Back home in New York, Forrest lost no time in casting Macready and his allies as conspirators out to ruin his career.

The pair’s rivalry gripped American audiences. When Macready arrived for a tour in 1848, Forrest and his fans dogged the Englishman’s every step. During a performance of Macready’s Hamlet in Cincinnati, audience members hurled half a sheep carcass on stage. Macready described Forrest as a ‘thick-headed, thick-legged brute’ in his diary. While Macready was engaged in Philadelphia in November and December, Forrest played at nearby theatres for 17 nights, matching his roles in a game of one-upmanship.

During this Anglo-American feud, nationalistic politics were taking hold in the US. The white, Protestant, nationalist Know-Nothing party had emerged from small groups like the Order of the Star Spangled Banner and the American Party to gain influence at local and national levels. The Know-Nothings supposedly earned their name from their stock response if caught by the police for one of the many quasi-illegal activities they engaged in: ‘I know nothing’. Know-Nothings were anti-Catholic, anti-Irish, anti-suffrage isolationists who believed that temperance, mandatory religious education in schools and severe immigration policies would generate economic prosperity.

There was significant cross-over between Know-Nothings, the city’s gangs and the patriotic B’hoys in theatre audiences, all of whom saw Forrest as their champion. His masculine, patriotic, tough-guy roles of rebels and revengers reflected their ideology and sense of heroic virtue. It is no surprise that many of his supporters, prejudiced against the city’s elite, would take to the streets when a British actor who was seen to hold open disdain for Americans appeared in New York.

Some of the major players in New York nativist politics saw the Forrest/Macready divide as a way to lash out at the establishment. Among them was Ned Buntline, real name Edward Zane Carroll Judson, a best-selling novelist, polemicist and agitator. Between books like The Mysteries and Miseries of New York City (1847) and the self-published weekly Ned Buntline’s Own, he railed against corrupt or immoral public figures from a nativist point of view. Buntline and his compatriots took advantage of the moment to create chaos by playing on the prejudices of New Yorkers.

When Macready opened his run at Astor Place a few days before the deadly riot, protestors packed the house and booed the Englishman off the stage. Swearing never to return, Macready prepared to leave for England, but was halted by an unprecedented show of unity by the city’s leaders. A long list of lawyers, merchants, business owners, as well as the city’s premiere authors, including Washington Irving and Herman Melville, published a petition begging Macready to stay. Likewise, the mayor agreed to call up troops to guard the theatre in order to ensure his safety.

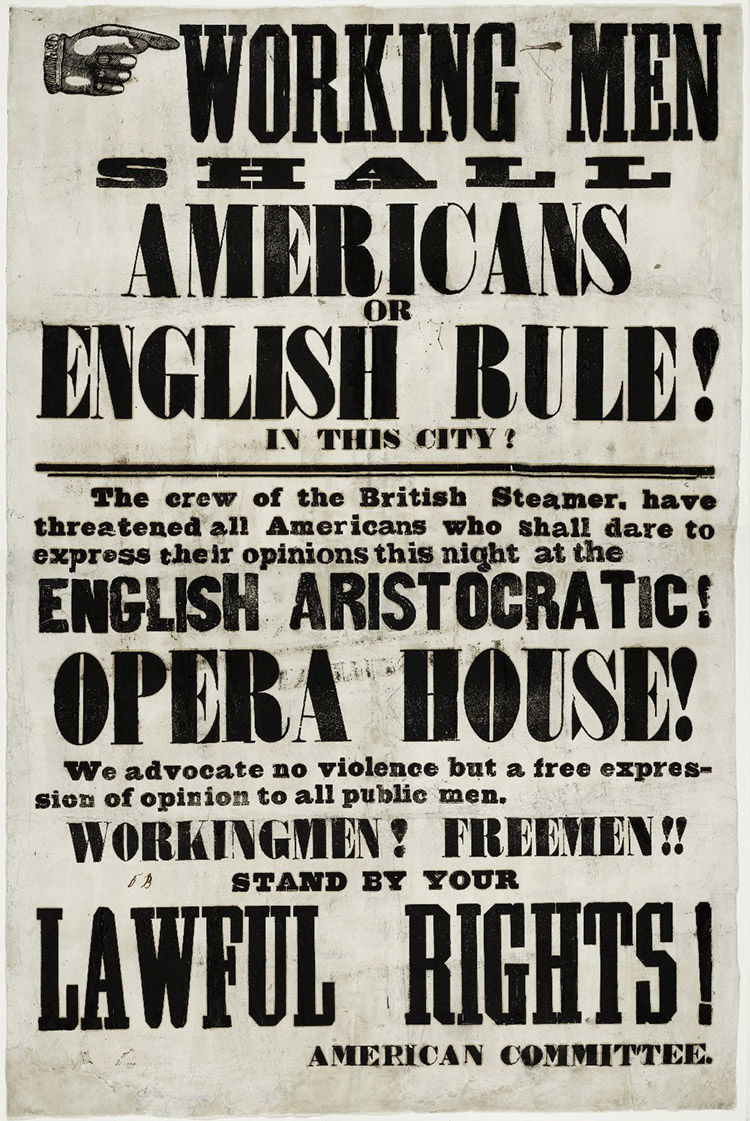

All of this seems to have mollified Macready, who announced his return in Macbeth for 10 May 1849. In response, Forrest announced he would play Macbeth at the Broadway Theatre a few blocks downtown. Sensing the possibility of publicity, Thomas Hamblin, actor and manager of the Bowery Theatre, did the same thing. Meanwhile, nativists – encouraged by Buntline and his ilk – posted bills over the city spreading a conspiracy theory that British sailors were preparing to attack the city that night. New Yorkers were urged to report to Astor Place to defend America. By evening, a crowd of thousands were gathered in the square to protest against Macready, the Opera House and the English.

When some audience members erupted at Macready’s entrance as the Scottish thane, the situation grew severe enough that local police called in militia regiments for support. The large crowd outside grew restless, hurling stones at the troops and theatre, causing significant damage. Eventually, the militia fired three volleys, dispersing the crowd, leaving 22 people dead and the city on the verge of mass revolt.

Inaugurated just a few days earlier, the Mayor of New York, Caleb Woodhull, issued a proclamation urging citizens to stay at home, but on the following day a crowd of thousands gathered at City Hall Park. Prominent Know-Nothing figures gave inflammatory speeches and the crowd vowed to destroy the opera house. Some 5,000 people marched uptown to Astor Place, shouting chants like ‘Burn the den of the aristocracy!’ This time, they were met by an organised, well-armed militia, which included foot soldiers, cavalry and artillery. After a few hours, the crowd trickled away, leaving the city in uncharted territory and poised for a literal class war. For several days, shipping was curtailed, with troops stationed around the city in anticipation of further unrest.

When no further conflict materialised, New York slowly returned to normal and an inquest into the riots was organised. The troops were found to be justified in firing and a few Know-Nothing ringleaders were sent to jail. Despite claiming that he was only at the riot to try to stop it, Buntline was sentenced to a year of hard labour. On his release he was met by a marching band and celebrations. While Forrest took a share of blame, few saw him as the cause. Macready, who had been planning to retire in America, returned instead to England to retire with his family in Dorset. The ‘Dis-Astor Place’ Opera House became a local joke and only remained open for a couple more years. Despite the violent memories, elite New Yorkers had briefly succeeded in creating their own theatre and had defended it with force. After 1849, American audiences grew increasingly divided as political debate grew more polarised in the decade before civil war threw the nation into bloody chaos.

Robert Davis has a PhD in the history of theatre and is author of the interactive novel Broadway: 1849. He is a contributing editor at Lady Science.