To Catch A Lady Burglar

‘Lady burglars’ – as they were primly named by the late-Victorian press – had an almost mythical status. That nocturnal robberies were committed by women was often too much to countenance.

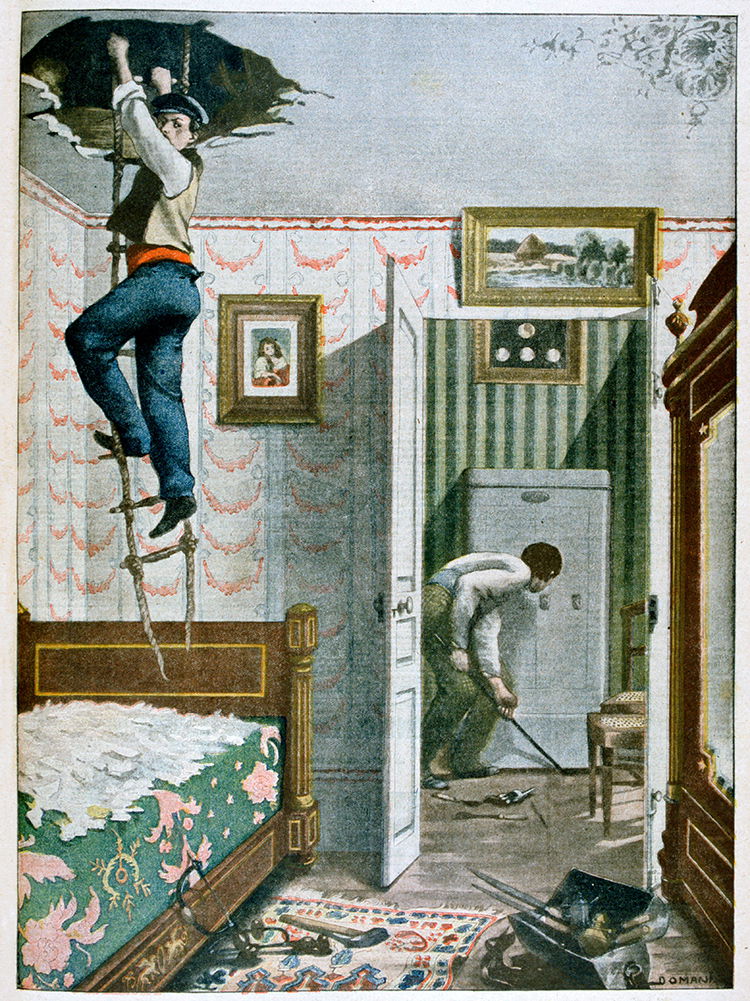

'A New Thing in Burglary', Illustrated Police News, 2 April 1898.

Patrolling past the comfortable suburban houses on Askew Road in Shepherd’s Bush, West London, one wintry early morning in February 1896, Detective Sergeant Knott noticed an ‘unusual light’ in the kitchen window of number 4. Instincts aroused, he called for two other police constables to join him, positioning themselves in neighbouring gardens where they watched, patiently, as Knott rapped on the front door. Gaining admittance, the detective dashed past its bewildered and apparently unsuspecting owner Mrs Hawkins to hunt down the intruder. What he saw gave him a shock. As Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reported,

When captured by Detective-sergeant Knott she was dressed in a stylish brown jacket with puffed sleeves, a black cashmere dress, and was wearing a pair of neat boots, since discovered to be the proceeds of one of the burglaries.

The burglar was Minnie Pheby, aged just 20 years old at the time, whose elegant appearance was, perhaps, a surprise exceeded only by the fact that she was a woman.

Women burglars – or ‘lady burglars’ as they were primly named by the late-Victorian press – held an almost mythical status in the popular and official imagination of the era. Burglary was considered a profoundly masculine crime. According to the Larceny Act of 1860, burglary (unlike its daytime counterpart, housebreaking) took place between the hours of nine pm and six am, i.e., the darkest hours of the night. It required a ‘breaking,’ whether through a door, window, or rooftop, either preceded or followed by theft from a domestic property, wherein residents were likely to be found asleep, vulnerable and unawares, when the criminal lurked nearby. These were the legal criteria for burglary until the Theft Act of 1968 collapsed both day and night-time crimes into one category, but until that time, the specific legal criteria for burglary recognised it as a form of villainy akin to rape. Haunting the homes (and nightmares) of the propertied middle- and upper-classes, its perpetrators were condemned as being as menacing to public safety as they were daring, cunning and dangerous.

Burglars’ disregard for the sanctity of domestic space was supposed to be matched by their athleticism. Journalist John Binny, who helped the social surveyor Henry Mayhew compile a book on London’s criminal ‘underworld’ in 1861, wrote of their skills thus

Breaking into houses, shops, and warehouses is accomplished in various ways, such as picking the locks with skeleton keys; inserting a thin instrument between the sashes and undoing the catch of windows, which enables the thieves to lift up the under sash; getting over the walls at the back, and breaking open a door or window which is out of sight of the street, or other public place; lifting the cellar-flap or area-grating; getting into an empty house next door, or a few doors off, and passing from the roof to that of the house they intend to rob; entering by an attic-window, or trap-door, and if there are neither window nor door on the roof, taking off some of the tiles and entering the house

Pheby amply embodied these skills, despite enduring stereotypes of women as passive and physically weak (increasingly challenged by the emergent women’s suffrage movement). Writing a memoir of his 40-year policing career in 1931, Detective Frederick Porter Wensley of the Criminal Investigation Department at Scotland Yard claimed that ‘Women are seldom master-minds in crime,’ suggesting their primary criminal activities were as accomplices to male burglars, for whom they might secure useful information about household routines. Yet Pheby had not only successfully burgled another house in Shepherd’s Bush owned by a Herbert Fryson prior to arriving at Mrs Hawkins’ home, she also conducted the ‘feat’ of gaining entry to that house by climbing through a window just eight inches across. Confronted by Knott in the kitchen of number 4, Pheby again displayed an athleticism and sang-froid more commonly associated with male criminals, as she resisted arrest by rushing out of the rear door the house with her bundle of stolen goods and jumping over a wall into the next garden, where she was caught by a waiting constable.

Fortunately for Pheby, the judicial system was just as unwilling to countenance the existence and abilities of women burglars as police officers were. Given nine months in prison for both burglaries (to run consecutively) following a trial at the Old Bailey, London’s Central Criminal Court, where she pleaded guilty, Pheby’s sentence was much lighter than those usually pronounced on male offenders and significantly below the maximum for burglary of penal servitude for life. This treatment was typical of the 1,184 women tried for burglaries across England and Wales during the period 1860-1939. The rare exception was Lydia Lloyd, who in 1879, having been convicted of burglary four times in the previous decade, was sentenced to over ten years imprisonment.

Otherwise, women burglars were canny about using the assumption that they had been ‘seduced’ into the crime by immoral men to their advantage in court. Sarah Hooper, tried for burglary at a house in Leyton, East London, alongside her husband in 1882, pleaded with the judge that: ‘All that I have done has been under my husband’s instructions.’ Sarah was given six months’ hard labour; her husband Charles was sentenced to five years. Such gendered sentencing patterns show us how broader fears about women’s changing social, political and cultural power bled into attempts to minimise their ‘success’ at joining the ‘aristocracy’ of thieves. Society recoiled from lady burglars’ disregard for the notion that ‘the Englishman’s home is his castle’, as they packed their jemmies and skeleton keys and strode off into the night.

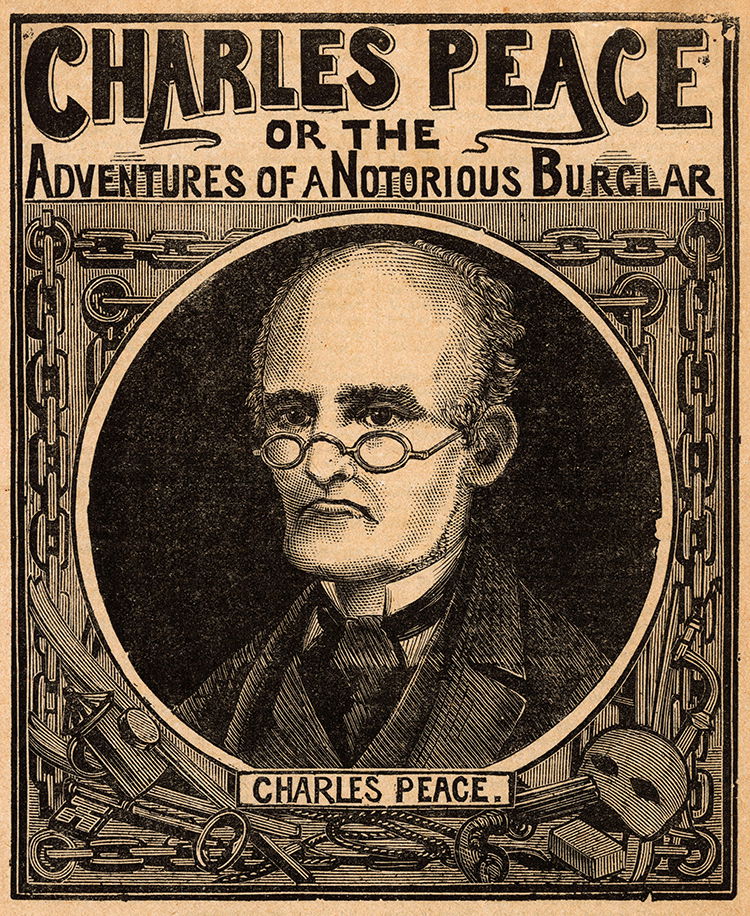

Certainly, there had been no earlier indications that Pheby would join the ranks of these burglars before her capture. A ‘quiet’ young woman described as ‘hard-working’ by her employers, Pheby was as adept at disguising her criminal intentions as other notorious Victorian burglars such as Charles Peace (executed 1879), who enjoyed a double-life as a violin dealer in Peckham while committing dozens of burglaries (as well as one murder) in a career spanning more than a decade. Peace’s exploits became the stuff of legend, retold in Penny Dreadfuls, theatre and films throughout the fin-de-siècle. Immortalised in wax at Madame Tussaud’s, ‘he’ was destroyed by fire in 1925. So beloved was Peace by visitors, however, that his waxwork was recreated and installed in 1928, where he sat, according to the exhibition catalogue, wearing ‘one of his numerous clever disguises’.

The retelling of Peace’s life recast the burglar as a romantic hero bent on the pursuit of pleasure, born into poverty but living the life of a gentleman through his criminal genius. Sustaining a pleasure culture of crime around burglary as an ‘art’ practised by handsome young men who would steal the jewels of wealthy women before seducing their owners, these stories coexisted with the warnings about burglary issued by police and insurance companies well into the mid-20th century. Indeed, the heroisation of burglars accounts for the commercial success of A.J. Raffles, ‘gentleman’ thief, a fictional burglar created by E.W. Hornung, brother-in-law of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, as a counterpart to Sherlock Holmes, who featured in 11 films (the last starring David Niven in 1939) from 1907. Notably gaining box-office success during periods of economic depression, the figure of the glamorous, sexy burglar suggests just how malleable attitudes towards crime have been in the past.

What became of Minnie Pheby? Undeterred by her first sentence in 1896, just six weeks after being released from prison in 1897 she was again found stealing clothes and jewellery from a dressmaker in Shepherd’s Bush, and recaptured by Detective Sergeant Knott, who it seems had chosen to keep a close eye on her. Feted once again by the press as an ‘unusual’ and ‘rare’ woman burglar, Pheby’s 12 months in prison marked only a short respite from her life of crime. In 1900, she ventured once again into theft, this time breaking into two houses in the area during the day, though in court an exasperated Knott highlighted that ‘recently no fewer than 15 houses had been broken into in the neighbourhood of Shepherd’s Bush and Hammersmith, and all had been carried out in the same way and in the peculiar style adopted by Pheby’. Still, apparently, disbelieving the woman’s ability, the judge sentenced her to 18 months’ hard labour, illustrating the sheer power of the imagined association between women and domesticity that prevailed into the 20th century. For Pheby, the beneficiary of this stereotype, the judgement provoked contempt. Turning to the court, she reportedly asked: ‘Is that all?’

Eloise Moss is the author of Night Raiders: Burglary and the Making of Modern Urban Life in London, 1860-1968 (Oxford, 2019).