The Changing Face of the Republican Party

The contrast between Abraham Lincoln and presidential candidate Donald Trump could hardly be more striking. Yet both men can be placed within the continually evolving politics of the Grand Old Party, argues Tim Stanley.

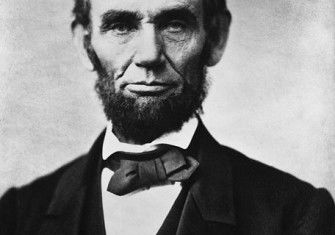

It was an unexpected sight. On September 3rd 2016, Donald Trump addressed an African-American church in Detroit and told them that he wanted to help write the next chapter in civil rights history. Trump said: ‘Becoming the nominee of the party of Abraham Lincoln – a lot of people don’t realise that Abraham Lincoln, the great Abraham Lincoln, was a Republican – has been the greatest honour of my life. It is on his legacy that I hope to build the future of the party.’

While most people do know that Lincoln was a Republican, very few regard Trump as a fellow traveller of the president who ‘freed the slaves’. One poll showed Trump getting just one per cent of the black vote in the coming presidential election.

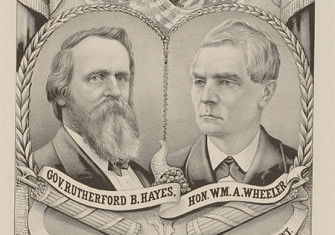

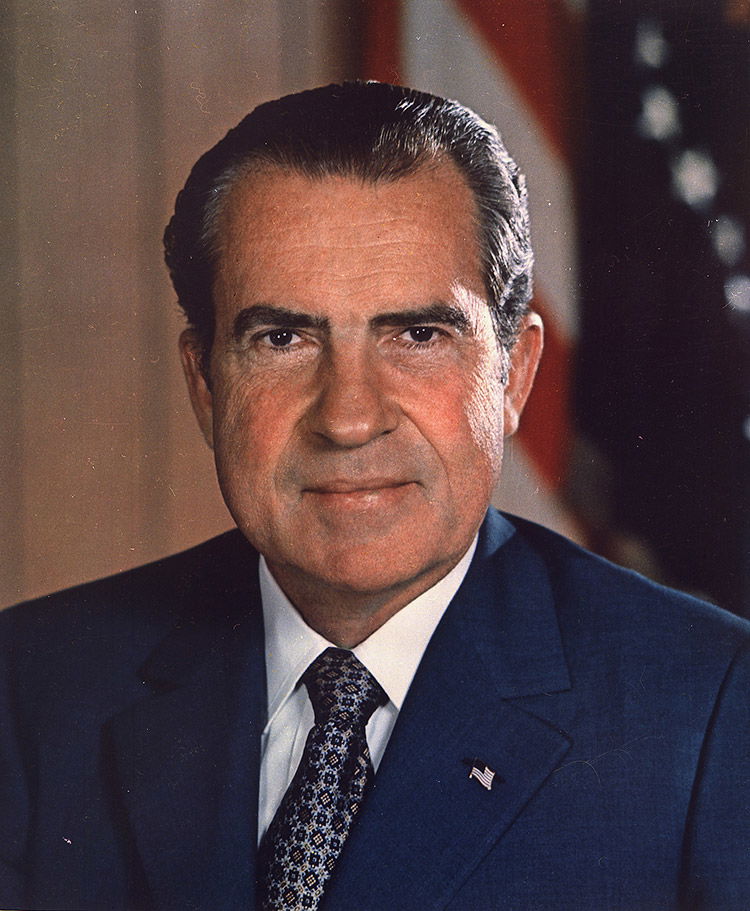

How do we explain the Republican Party’s journey from Lincoln to Trump? Some conservatives insist that it is not that great a distance, that Republicans have always been committed to equality before the law and individualism. But changes in voting patterns suggest profound evolution over time. From the mid-19th century to the early 1930s, the Grand Old Party (GOP) was a largely northern phenomenon, which could count on the significant support of African-Americans thanks to its association with Lincoln. It was a home to social reformers, notably Theodore Roose- velt, who used federal machinery in the early 1900s to regulate society along more progressive lives. As late as the 1970s, President Richard Nixon, a descendant of anti-slavery Quakers, introduced affirmative action into federal employment contracts and quietly desegregated the nation’s schools.

Nixon in the 1970s and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s won landslides that swept the country. Yet the scope of their victories disguised the emergence of new regional biases. As the Democrats took a more leftward turn from the mid-20th century, so the Republicans shifted to the right and the electoral map flipped. The GOP is now a nearly all-white party with a political base in the South and West, while the Democrats have taken over the 19th-century Republican strongholds of the North.

There is a consensus that voting patterns have changed because the parties’ ideologies have changed. It is hard to dispute this. The contemporary Republican Party is broadly opposed to big government and perceived as willing to court racist sentiment. Its criticism of civil rights reforms in the 1960s is a historical stain that many minority voters and liberals refuse to forgive.

There are, however, grounds upon which to challenge this smooth narrative arc from Lincoln’s progressivism to Trump’s reactionary conservatism. One is that the party has changed several times during its century and a half of existence, veering from left to right according to political necessity and the personalities in charge. In some ways, Trump is actually more concomitant with earlier forms of Republicanism than Reagan or George W. Bush were.

Second, even with all these policy revisions there is evidence of continuity. If you see political history as shaped entirely by intellectual argument, then the dots are hard to connect. If you see it as less a competition between ideas than as a competition between life experiences and interests, then it is possible to argue that the GOP represents a certain ethic, which is Protestant capitalism. Its ongoing mission is to expand the self-reliance of the individual.

The Republicans gathered in Philadelphia in 1856 to nominate their first ever candidate for the White House. They settled on an eccentric celebrity explorer called John C. Frémont of California. Abraham Lincoln, a lawyer from Illinois, received a few votes for vice president, but the slot eventually went to William L. Dayton. The party’s unifying issue was opposition to the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which opened up the two new territories to slavery. The Republicans, while not abolitionists per se, saw this as an aggressive attempt to advance slave-holding and an affront to the principles of the Declaration of Independence. On the stump, Lincoln summed up his party’s views: ‘The Republicans inculcate … that the Negro is a man, that his bondage is cruelly wrong, and that the field of his oppression ought not to be enlarged.’ Frémont and Dayton did rather well in the election, taking a third of the national vote. Four years later, Lincoln would win the presidency, triggering the South’s secession from the Union and a terrible civil war.

The Republicans’ 1856 platform did not only talk about slavery. It also dreamed of giving free land to farmers in the west – ‘free soil’ – and a larger role for banks and industry in the developing economy. The party made a curious connection between slavery and Mormon polygamy, calling them the ‘twin relics of barbarism’ in the US territories. The Republicans saw themselves as a force for modernity.

The new party tapped into an old debate about American identity. The revolutionary founders of the United States prized individual liberty and sought to maximise it: liberty from Britain, from banks, from the state. Liberty was broadly understood to be racialised. Black people were often regarded as incapable of freedom; a white man’s freedom was both a birthright and proof of biological superiority. So a white people’s government had to have a touch so light as to be non-existent. That was the view of the Democratic party, which won election after election pledging to keep the state small and the public unchained.

But how does a nation with no government defend itself and uphold the law and thus remain free? Some Americans concluded that it could not. While remaining committed to liberty and constitutionalism, a Whig coalition, often comprising upscale business interests in the industrial north east, argued that there was a limited role for government to play in finance and industry. They also addressed another contradiction that bothered highly religious Americans: how could they respect limited state interference while also maintaining public morality? If the republic was socially unregulated, they argued, then it would descend into decadence. Men and women would be enslaved to alcohol and sex, the republic would rot from within. For these Americans, the link between slavery and polygamy was obvious – both were sins that threatened everybody’s freedom.

These people were largely pietists: European émigré Protestants who believed the faithful should lead vigorously Christian lives. They hated booze, they hated Catholicism. What was the point of winning independence from Britain if it was to be replaced by rule from Rome? A new electoral dynamic emerged. Catholics and non-pietists gravitated towards the Democrats. Pietist Protestants favoured the Republicans – and the GOP remained fairly consistent in the years to come in its argument that private mores have to be open to state sanction, if liberty is going to escape the bondage of human desire.

Every coalition contains contradictions: Lincoln’s faith was difficult to nail down and an ugly rumour said Frémont might have been a Catholic. The way that the Republicans evaded disagreement was to focus overwhelmingly on opposition to the spread of slavery, a message heavily coded with moralism. Visiting the South, William H. Seward, a prominent Republican, wrote that he discovered: ‘An exhausted soil, old and decaying towns, wretchedly-neglected roads, and, in every respect, an absence of enterprise and improvement.’ Slaves did not give their labour willingly, so it was of low quality. Slave masters did not have to physically work for a living, so they became lazy and sinful. The historian Eric Foner argues that the Republicans were Yankee cultural imperialists spreading an ideology of ‘free soil, free labor, free men’, the belief that capitalism, like the Holy Spirit, could liberate and redeem. Little did they know that terror of this philosophy among southerners would spark civil war.

Fighting broke out in 1861 and by the end of the Civil War in 1865 the role of the federal government had been transformed way beyond what the Republicans imagined or even desired. They found themselves in charge of something much closer to a unitary state. Lincoln’s assassination deprived the GOP of leadership; in the fight to come, a radical bloc in Congress took control and effected a major reconstruction of Dixie. Railroads and schools were constructed; whites flooded south to serve as teachers, missionaries and investors. There was a serious attempt to impose a free labour economy by force of arms. This was perhaps the high water mark of Republican governmental activism. It was also a failure. Recession dried up the money; the North’s will to reform the South receded in the wake of violence and corruption and the troops were withdrawn, allowing racists to retake control of the South and institute segregation.

As would so often be the case, Republicanism defined itself by what it would choose not to do when given power. Its ranks contained liberals, but they were constrained by dislike of excessive government and a preference for capitalism as a motor of change.

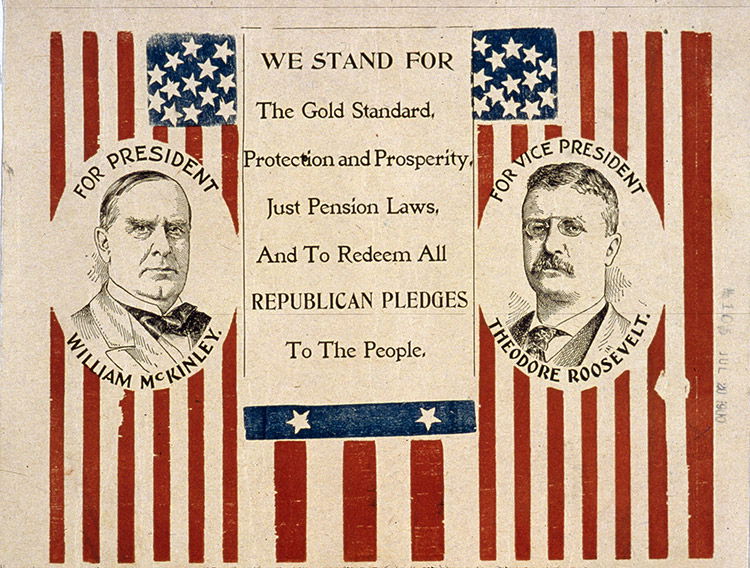

It is hard to read the early Republican party through the lens of today’s ideological partisanship. At times it might appear reactionary, at others enlightened. Throughout most of the postwar period it favoured pro-business protectionism and was associated with the conspicuous consumption of the Gilded Age, with a degree of splendour that would put the gold-coloured Trump empire to shame. But in the early 1900s, the party embraced progressivism. Theodore Roosevelt, president from 1901 to 1909, tried to curb the power of big corporations through anti-trust suits, regulated the provision of clean food and drugs and was a keen conservationist. In 1916, Republicans elected the first woman to Congress (Jeanette Rankin), the first Jewish senator from outside the former Confederacy (Joseph Simon in 1898) and the first Hispanic senator (Octaviano Ambrosio Larrazolo in 1928). The Democrats, by contrast, were settled as the party of big cities in the North, small farmers out in the West and the South’s racist white rulers.

Again, however, there was continuity between progressive and anti-slavery campaigns. Both were the manifestation of a Protestant middle class trying to square its understanding of America’s founding ideals with sudden and alarming social change. For instance, in 1833 Chicago contained just 360 people. By 1900 its population was 1,698,575. That meant disease, poverty, disorder. It also meant the emergence of unions and big city political machines across the North dominated by immigrants that, in the view of many Republicans, threatened to put power in the hands of the mob.

In 1894 the American Railway Union in Illinois went on strike against the Pullman Company. George Pullman fancied himself as an enlightened Yankee: he built a model company town that offered healthy living free from smog and alcohol and even hired black workers. But during a downturn he was forced to lay people off and cut wages. Some 250,000 Pullman employees walked out in a strike so devastating to the region’s economy that federal troops were sent in to crush it. Around 30 were killed in riots and sabotage.

It was clear that the GOP’s strategy of growing domestic industry through a tariff on imports was no longer enough to avert revolution. Progressive social reform was thus an act of self-preservation. It also tapped into a deep well of lingering pietism. Theodore Roosevelt’s America was a place heaving with Christian ambition, where John Harvey Kellogg, a Michigan doctor, invented corn flakes in the hope that a plain diet would somehow stop people masturbating and Carrie Nation, the temperance advocate, stormed into saloons with her hatchet crying ‘Smash ladies, smash!’

Roosevelt, likewise, saw redemption for America in work, self-discipline and even violence. In 1899 he said:

When men fear work or fear righteous war, when women fear motherhood, they tremble on the brink of doom; and well it is that they should vanish from the earth, where they are fit subjects for the scorn of all men and women who are themselves strong and brave and high-minded.

Roosevelt’s progressivism sought to shape a healthy, vigorous populace. The alternative was a new form of slavery: slavery to indolence and pacifism. It is thus impossible to separate the Republican campaign against poverty with its campaign against liquor, which culminated in the introduction of prohibition in 1920.

Progressivism went too far for some Republican stalwarts. Roosevelt’s successor, William Howard Taft, proved more conservative in tone and Roosevelt decided to challenge him for the party’s nomination in 1912. The contest was decided at the convention, where black delegates from the South helped put Taft over the top. Roosevelt ran as a progressive independent in the general election and split the Republican vote, putting Democrat Woodrow Wilson in office. After the First World War, the party appeared to adopt a more ideologically conservative line. Government shrunk in size and not only domestic ambitions were affected. The Republican party of the 1920s favoured non-intervention in world affairs.

Yet even during this period, progressive instinct remained. Take Herbert Hoover, president from 1929 to 1933. He believed that poverty could be cured through cooperation between government and business, which he called volunteerism, but he rejected socialism as a solution to free market failure. When the Great Depression hit, his response pushed volunteerism to the limit of how much government a Republican could accept. He signed off on raised tariffs to protect industry and the forced repatriation of hundreds of thousands of Mexican migrants to free up jobs. He even turned on the money tap with the Emergency Relief and Construction Act, financing the variety of programmes that would later be associated with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Democratic New Deal. But Hoover ultimately could not break with the Republican instinct to favour free markets and individual effort as the solution to all ills. His refusal to go further probably contributed to his landslide defeat in the 1932 election.

The New Deal of the 1930s, like reconstruction and progressivism before it, transformed public expectations of federal government. Suddenly it took responsibility for public housing, unemployment insurance, even farm prices, and Republicans had to decide whether to accept these changes or try to roll them back. The debate was rancorous.

On one side stood moderate Republicans, pragmatists such as Dwight D. Eisenhower, who felt that the New Deal should be trimmed and made to work but not generally repealed. Eisenhower’s presidency (1953-61) was dismissed as ‘do nothing’ but now looks surprisingly interventionist. He expanded social security and raised the minimum wage. Federal troops were sent in to desegregate a high school in Little Rock, Arkansas. A new Department of Health, Education and Welfare was created. The Interstate Highway Program transformed transport in the US at enormous cost to the public purse; Eisenhower said that it required enough concrete to build ‘six sidewalks to the moon’. And cheering along these works were a group of northern politicians who were dubbed Rockefeller Republicans in honour of Nelson Rockefeller, the charismatic and vigorously progressive governor of New York from 1959 to 1973.

As Eisenhower’s second term came to an end, his vice president, Richard Nixon, yearned to replace him and needed a united GOP to do so. In July 1960 he met Rockefeller at the latter’s sumptuous Manhattan apartment to agree a statement on the direction of party policy. Rockefeller set terms. The resulting Treaty of Fifth Avenue called for federal aid to education and the elimination of ‘the last vestiges of segregation or discrimination’, presumably a form of comprehensive civil rights legislation.

Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona described the Treaty as ‘the Munich of the Republican Party’. He represented a body of conservative opinion just beginning to evolve into a cohesive movement. It was diverse; there were religious conservatives who wanted to roll back the tide of moral liberalism; there were racial conservatives who wanted to defend southern segregation; and there were economic conservatives who believed government spending was inflationary and increasingly unconstitutional. Goldwater’s western provenance was significant. Money and political power were now floating away from the big cities and towards the growing suburbs located in the South and West. A new, white collar middle class was emerging that resented paying high taxes to bankroll the poor. Often that grievance had a racial subtext. Far more whites than African-Americans received government dollars, but public perception was that welfare was a black thing.

Goldwater ran for the 1964 Republican nomination and opposed that year’s critical civil rights bill. Rockefeller fought him bitterly for the nomination in a battle that makes contemporary US politics seem tame. Goldwater was tarnished as a crank; Rockefeller was hurt by his divorce and remarriage to a much younger woman. Goldwater’s triumph was hollow and he lost the general election in a landslide. Yet his opposition to the Civil Rights Act earned him the votes of the once-Democratic South, putting them on the road to entering the Republican fold for good. Did Goldwater consciously play the race card in 1964? The general consensus is that this was his strategy; after all he told an audience of Georgians that chasing black votes was a waste of resources and that the GOP should ‘go hunting where the ducks are’.

On the other hand, Goldwater’s biography contains little evidence of personal racism. He had opposed segregation back home in Arizona and had supported the 1957 and 1960 civil rights bills in the Senate. His opposition to the 1964 Act, he insisted, was based on its attempt to compel employers to serve and hire African-Americans, something he regarded as unconstitutional. This view was consistent with Republican criticism of civil rights activism throughout the 1960s. As with Hoover and state action to alleviate poverty, they supported racial progress in principle but said that they favoured volunteerism in approach. This, again, proved useless to those who needed federal support.

The Republicans struck another compromise. Nixon had a second go at the presidency in 1968 and won. His administration played a tough game with leftist radicals such as the Black Power movement but actively pursued desegregation in education and employment through federal agencies. Nixon got away with this double standard by doing what the Republicans had done in the 1850s: he exploited a unifying theme. Theirs had been anti-slavery. For the postwar Republican Party it was anti-communism.

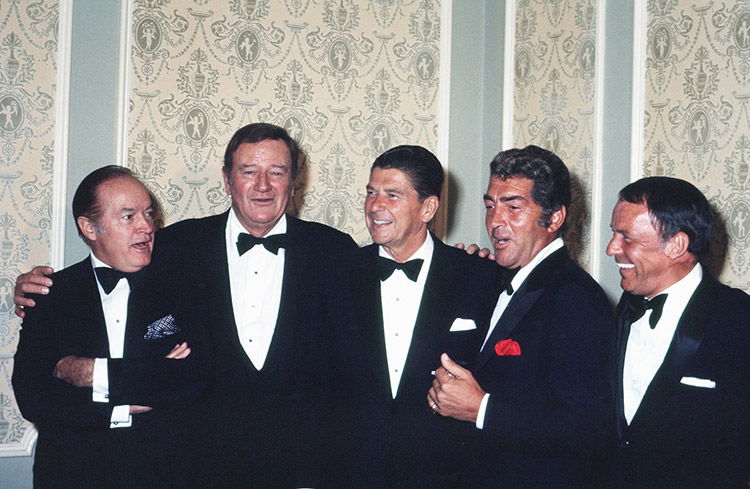

Rockefeller, for instance, might have been soft on domestic policy, but on foreign policy he shared the conservative desire to contain, even confront, the Soviet Union. Hatred of communism bled into support for Vietnam and opposition to growing social disorder associated with the anti-war movement. In fact, anticommunism allowed Republicans to govern and talk in contrary ways. Ronald Reagan made his name as a national politician stumping for Goldwater in 1964 and won the California governorship in 1966 with a little help from Goldwater’s pal, the actor John Wayne, an ideologue who helped endow conservatism with a cowboy mythology. Once elected, however, Reagan managed his state in Rockefeller style: he signed off a massive tax increase and took liberal positions on abortion and divorce. Conservative voters were kept happy by the Republicans throwing Reagan into confrontations with student protestors, but it was largely theatrical.

Reagan went on to serve two hugely popular terms in the White House. By the time he stepped down, in 1989, the Rockefeller Republicans were largely out of office; the states that once supported them drifted towards the Democrats. But even as the GOP appeared to have been ‘hijacked’ by a new ideological conservative movement, old aspects of Republicanism remained.

Reagan’s alliance with Christian conservatives who railed against pornography, abortion and homosexuality was exactly the same as the GOP’s former courtship of pietists opposed to alcohol. His opposition to communism was framed as a second war against slavery, a term that he also applied to welfare dependency. Like the earlier ‘free soil, free labor, free men’ Republicans, Reagan regarded free markets as redemptive. Faith in democratic capitalism made the US exceptional, a world leader. ‘Lincoln understood’, said Reagan in a 1987 lecture to high school students, ‘that the idea of human liberty is bound up in the very nature of our nation. He understood that America cannot be America without standing for the cause of freedom.’

What made invocations of Lincoln appear ridiculous in the 1980s was the GOP’s by now total split from the black rights movement. Civil Rights activists had concluded that economic rights were inseparable from political rights and that the next stage in their historic battle was to demand government intervention in the economy. This was something Reagan could not accept. It is not entirely true that the GOP walked away from civil rights. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that the two movements took different directions in which neither was willing to follow the other.

Reagan’s association with white middle-class populism did his party long-term damage. It alienated non-whites, tying the GOP to a demographic that was large but, in fact, in slow decline. Since 1968, the Republican presidential nominee has won the white vote in every single election, but the white vote is diminishing and the GOP’s failure to see that could turn it permanently into a minority party.

Reagan’s cowboy image also popularised the idea that a successful Republican is one who stands his ground, even though he was often given to compromise. Worse, his electoral success as a conservative gave the impression that ideological conservatism and Republicanism are synonymous when, historically, that has not always been the case. Synchronicity between the conservative movement and the Republican party was unsustainable.

Unity was shattered by the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, served one term in the White House and then faced a significant primary challenge in 1992 from former Nixon speech-writer Pat Buchanan, who demanded that the Republican Party follow the logic of the end of the Cold War, withdraw from foreign entanglements and put America first by protecting jobs with new tariffs. The latter issue found a constituency among Reagan voters whose jobs were being shipped off to China. Buchanan won no primaries in 1992, but his candidacy weakened Bush and contributed to his defeat at the hands of Bill Clinton. The Trump rebellion in the GOP ranks has been brewing since the early Nineties.

One reason why it took until 2016 to fully materialise is because President George W. Bush skilfully held the Republicans together in the early 2000s. This time the Republicans were united by opposition to radical Islamism, which, yet again, was cast as a war on slavery; ridiculous comparisons were made between Bush and Lincoln as wartime leaders. But the disaster in Iraq discredited interventionism, while the credit crunch cast doubt on the wisdom of tax-cutting Reaganomics. Trump surged in 2016 in large part because policies the GOP establishment had backed had failed. His opponents in the primaries offered nothing new. They did, however, parrot conservative talking points that had been around for several decades and their complete, humiliating defeat proved that ideological conservatism is only one constituency of ideas within the Republican party.

As for Trump, he breaks so many rules that he seems like a repudiation of the grand Republican tradition. On the contrary, many of his themes are familiar. He is a Yankee, as Republicans overwhelmingly used to be. He promotes scepticism about foreign engagements, as the party did in the 1920s, and threatens to use mass deportations as an economic tool, just as Hoover did during the Great Depression. His support for limited protectionism is straight out of the GOP’s post-Civil War playbook. He sees the potential in infrastructure spending, as did Eisenhower.

Most importantly, Trump is a propagandist for American capitalism. It is true that he has sometimes eschewed Republican pieties: in the early primaries he said only that he wanted to make people richer, not better, citizens. But his rhetoric has evolved. He has increasingly paid lip service to the idea that religion and cultural conservatism are essential to national well-being, while his desire to be seen singing and dancing in African-American churches gives his candidacy the air of being in the Lincoln tradition. In fact, even if Lincoln’s practical approach to civil rights has not been consistent in Republican history, the desire of Republican nominees to insist that it is generally has been.

Yes, Trump is different from George W. Bush. But the fact that Bush was different from Rockefeller who was different from Hoover who was different from Lincoln reminds us that Republicanism is flexible and responsive to social change. There runs through its history a thin thread of dedication to individualism and free markets. That history is a story of an ongoing negotiation between principle and pragmatism, a negotiation that pragmatism has generally won. What it is not is a story of ideological conservatism triumphant. Trump is not a conservative, but he very much is a Republican.

Tim Stanley is an associate fellow of the UCL Institute of the Americas and the author of The Crusader: The Life and Tumultuous Times of Pat Buchanan (Thomas Dunne, 2012).