Colouring The Past

The development of interior painting schemes has a colourful, if hazardous, history.

Patrick Baty has worked as a historic paint specialist on an impressive array of buildings and monuments, from Hampton Court Palace and Tower Bridge to the National Trust’s Uppark House. In The Anatomy of Colour he takes us on an inspirational journey across 300 years of changing paint and colour palettes used in interior decorating from 1650 to 1960, focusing on colour schemes, paint types, colour theory and house-painting practice.

Patrick Baty has worked as a historic paint specialist on an impressive array of buildings and monuments, from Hampton Court Palace and Tower Bridge to the National Trust’s Uppark House. In The Anatomy of Colour he takes us on an inspirational journey across 300 years of changing paint and colour palettes used in interior decorating from 1650 to 1960, focusing on colour schemes, paint types, colour theory and house-painting practice.

The book begins with an exploration of the history and use of the different types of paint and pigments, from ivory black, made from the offcuts of the comb-making industry, to pink, which originally signified a yellow pigment and only became associated with the light red colour we think of today in the early 18th century. We gain insights into the hazardous conditions experienced by barefooted female workers working in white lead manufacture in cities such as Newcastle and Sheffield in the 19th century and the alarming use of the toxic arsenical green in wallpaper-making in England right up to 1880. There was scant regard for health and safety, especially for those workers endeavouring to meet increasing demand for new paints. Cheaper colours used in interior decoration were called common colours, while the use of expensive colours, such as pea green, openly proclaimed the wealth of the owner.

House-painting was initially the preserve of professional painter-stainers, but after the Fire of London in 1666 there was a relaxation of standards amid the huge programme of rebuilding required. Together with the increasing availability of semi-prepared painting materials from the colourman, a new breed of merchant, and of manuals published to advise on the methods and materials required, DIY became the way forward. Over the next 130 years, new materials, colours and systems followed, influencing social taste.

The 19th century heralded the arrival of machine-printed wallpapers, brilliant new pigments such as chrome yellow, emerald green and the synthetic French ultramarine. Baty writes of the importance of durable wipe-clean paint surfaces in Victorian houses lit by soot-producing oil and gas lamps.

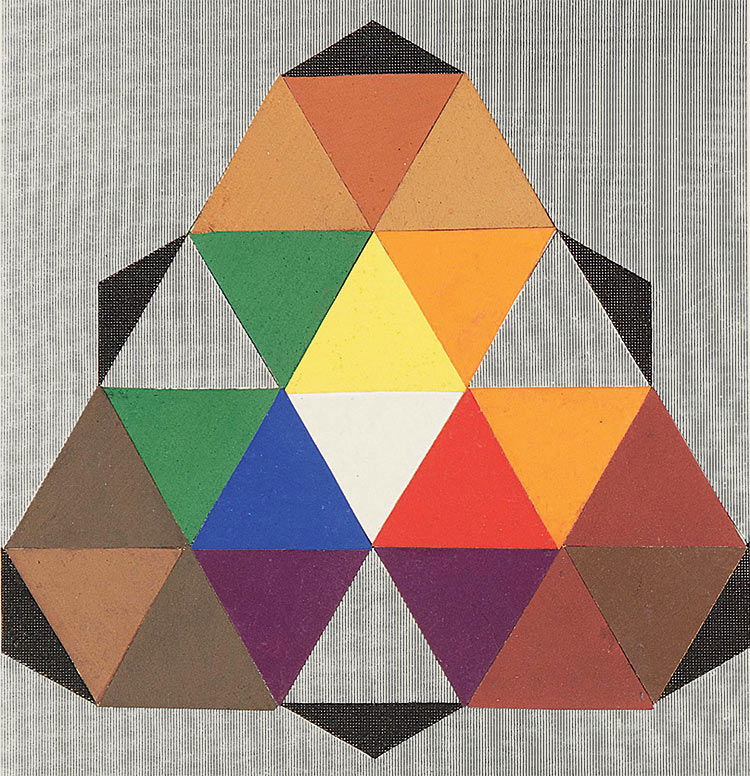

Colour was not only important to house-painters. In an age of discovery and scientific progress, those from backgrounds as diverse as geology, horticulture and ornithology laboured towards the ideal of a universal system for classifying colours. Sailing on the HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin carried a copy of a recent work, which allocated animal, vegetable and mineral equivalents to each of the 110 colours identified by its author.

It was only in the 20th century, with the introduction of British Standards, that a recognised scheme for identifying paint colours was introduced. Postwar Britain’s interiors were transformed by the arrival of emulsion paint, concrete, plastics, open-plan living and the revolutionary Colorizer paint-mixing system.

Baty is keen to point out that his book is not meant to be ‘a history of decoration or to provide a prescription of how to decorate’, but rather to show the colours from different periods and explain how they were used and standardised.

The Anatomy of Colour is lavishly illustrated with stunning photographs of restored decorative schemes in historic houses and contains pages of colour samples and colour charts taken from a wide selection of period manuals, manufacturers’ ranges and colour standards. There is also a useful glossary of technical terms used.

From a practical point of view, the book is not always easy to navigate and at times the print is uncomfortably small. The absence of explanatory footnotes could be a problem for those wishing to use it for academic purposes. However, as a guide to the changing theories, standards and use of colour in interior decorating over the past 300 years, this is a unique and highly informative work, unlikely to be surpassed.

The Anatomy of Colour: The Story of Heritage Paints and Pigments

Patrick Baty

Thames & Hudson 352pp £35

Fiona Mann is an independent art historian, whose doctorate researched 19th-century artists’ pigments, materials and techniques.