‘The Wild Men’, ‘The Men of 1924’ and ‘A Century of Labour’ review

On the centenary of Britain’s first Labour government, three recent histories cast a sympathetic eye over Ramsay MacDonald’s nine months in Number 10.

Ahead of a possible Labour victory in Britain’s next general election, three new histories published on the centenary of the party’s first government provide a useful opportunity for reflection and perspective. Peter Clark’s brisk and personable The Men of 1924 devotes roughly half its length to Labour’s early years, as the party transformed itself ‘from pressure group to government in waiting’. Formed in 1900 from the trade union movement and a patchwork of small and frequently fractious socialist parties, societies and groups with origins in the late 19th century, the party’s initial electoral successes were limited to the local level but had wide-ranging reach. In its early strongholds in the Welsh valleys and poorer London boroughs such as Poplar, Labour councillors focused on improving working conditions and on health, housing and education, often building in microcosm the mechanisms of welfare that would be introduced nationally under Labour governments of greater success and stability than that of 1924.

The election of December 1923, in which a shock electoral advance by Labour led to an unprecedented three-way split in the Commons, saw the party enter government a month later for the first time. At a century’s distance, this nine-month-long minority administration – a venture cautioned against at the time by some of its own members – tends to be treated as an embarrassing failure or false start at best. Both Clark and David Torrance, in his more tightly focused The Wild Men, offer more even-handed assessments of the 1924 government. Both authors also paint largely forgiving portraits of its leader Ramsay MacDonald – although his political achievements and his personal snobbery, prickliness and social climbing have been judged so harshly by the majority of Labour’s historians that the bar for sympathy is somewhat low. Clark’s series of biographical sketches, and Torrance’s more smoothly integrated study, bring in the personalities beyond MacDonald that shaped Labour’s brief time in power: Lancashire autodidacts Thomas Shaw and J.R. Clynes; Fabian intellectuals such as Sidney Webb; the avuncular Arthur Henderson and the brash and bibulous Jimmy Thomas.

Other than Margaret Bondfield, the former shop assistant and trade union activist who would later became Britain’s first female cabinet minister in the second Labour government of 1929-31, this story reflects the domination of 1920s British politics by what Clark, pre-empting the obvious observation, acknowledges as ‘white men in dark suits’. Both books do, however, draw on some of the many female voices behind the scenes, including Beatrice Webb, Dolly Ponsonby and journalist Mary Agnes Hamilton. The 1924 Housing Act, enabling the subsidised building of public housing, was driven by health secretary John Wheatley’s experience of rent strikes in Glasgow – collective actions which were largely led by women. Labour’s electoral success reflected the rising influence of newly enfranchised demographics – both women and working-class men – and, in terms of class, was unarguably groundbreaking. MacDonald himself was the illegitimate son of a housemaid and a farmhand, and his cabinet replaced Old Etonians with former miners, railwaymen and millworkers.

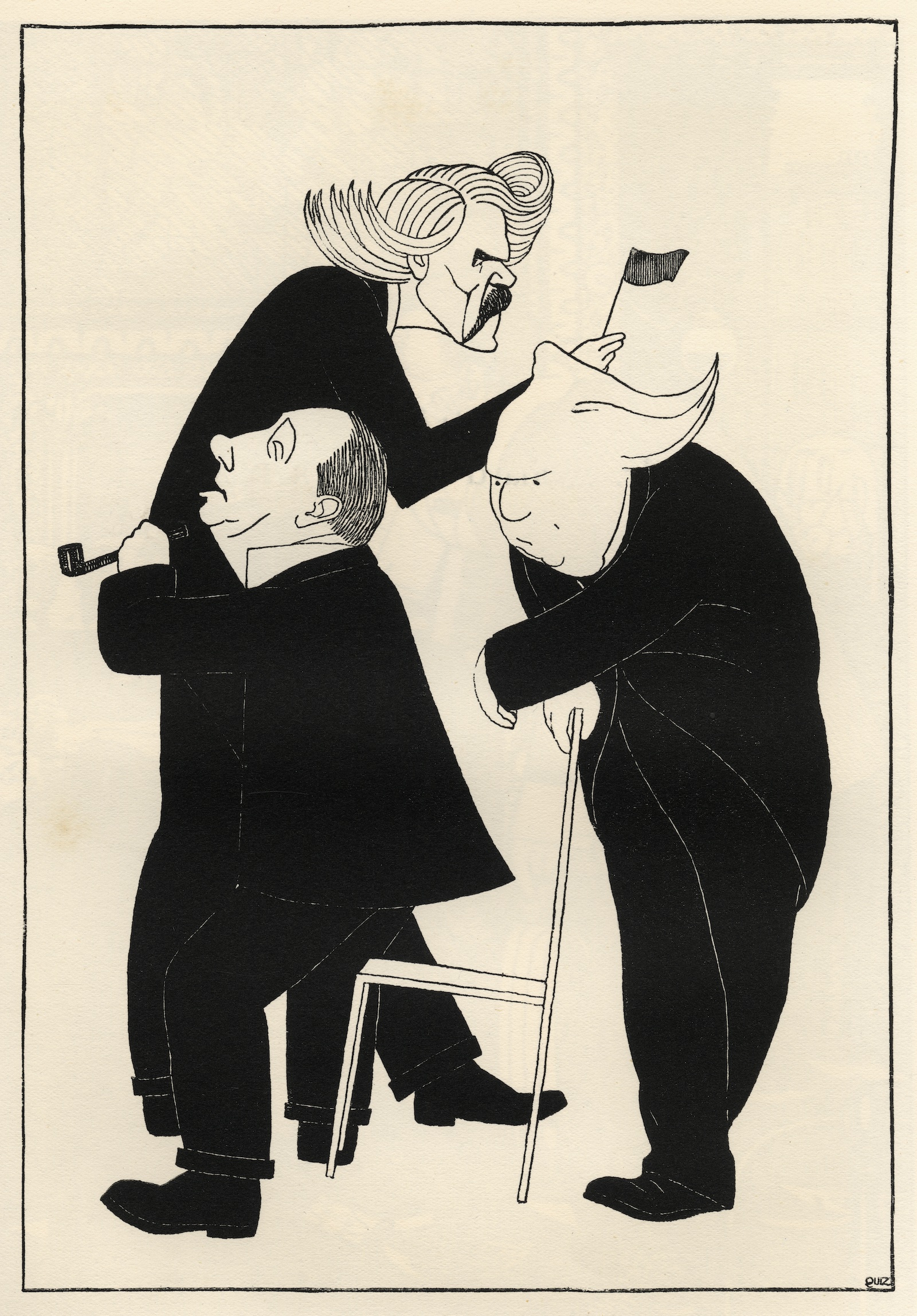

These sweeping changes to the kind of country Britain was, and who held power in it, were in turn reflected in the reactions of the country’s establishment. The Men of 1924 emphasises the entrenched social and political privilege that the Labour government disrupted, the context of a socialist surge in Europe that it was variously feared and hoped to form part of, and the anxiety and furore this generated as opponents in both Parliament and the press railed against the imminent ‘horrors of Socialism and Confiscation’. In this atmosphere of political and cultural upset apparently minor matters took on major importance. Both Clark and Torrance note the intriguing politics of clothing, with some new Labour MPs seeking to show their fitness to govern by adopting Parliament’s traditional trappings – including frock-coats, white tails and opera hats – while others, contemptuous of such concessions, entered Parliament defiantly dressed in their ten-year-old lounge suits.

In what would come to be a regularly repeating pattern, the administration was preoccupied with proving its fitness to govern in both style and substance, even if this meant disheartening or antagonising its own supporters. The minority government faced what Torrance identifies as a strikingly modern litany of difficulties: instability and exhaustion caused by incessant changes of political leadership, financial crisis, industrial action and clashes with the civil service. Those difficulties also included media manipulation of fears over Russian intrusion into British politics, as demonstrated by the still-murky intervention of the ‘Zinoviev letter’ – a fabricated missive from the head of the Communist International to the Communist Party of Great Britain welcoming the prospect of a Labour government, published by the Daily Mail just before the general election in October 1924. On taking office MacDonald sought to reassure a rattled country through ministerial appointments that included former Liberals and even Conservatives, along with trade unionists and socialist intellectuals. He shied away from his party’s proposals for nationalisation of industry and a one-off wealth tax or ‘capital levy’, even though the 1919 Liberal-commissioned Sankey Report on coalmining had recommended the former, and the ‘war socialism’ of rationing meant that state intervention was neither practically nor philosophically beyond imagining. With the exception of the Housing Act, this impasse and hesitancy to sanction more radical measures left the government able to offer little more than palliatives. Read alongside Torrance’s in-depth study, Clark’s final chapter on Labour in office seems almost an afterthought, but gives a useful chronology of its chaotic nine months, beset by internal tensions and external hostility that culminated, after a vote of censure, in MacDonald’s request to the king to dissolve Parliament in preparation for yet another election.

In 1924 MacDonald wrote: ‘The difficulties of the Party are within more than without.’ In Jon Cruddas’ thoughtful retrospective A Century of Labour, the party remains dogged by the difficulties of sustaining – much less reconciling – its volatile mixture of factions, tendencies and sectional interests. Cruddas, longstanding MP for Dagenham & Rainham, gives succinct mappings of Labour’s origins and history that bookend a detailed thematic exploration of its fortunes from 1900 to today, a journey in which landmark victories under Clement Attlee in 1945, Harold Wilson in 1966 and Tony Blair in 1997 arise from an otherwise unpromising morass of ‘waste’, ‘strife’ and ‘wilderness’.

Rather than the strains of social democracy versus socialism, Cruddas frames Labour’s intellectual history around competing theories of justice. These ideas stem variously from traditions of utilitarianism, radical democracy and ethical socialism, drawn from progressive movements both predating and beyond Labour as well as asserted to varying degrees within the party. This approach allows A Century of Labour to productively transcend more familiar analyses of the party’s defining conflicts. Nonetheless, its narrative also sees the pressures that Clark and Torrance pinpoint in 1924 continue, with cautious, pragmatic gradualism in government – even when based on a belief in socialism’s inevitability – too often becoming conservatism or paralysis, while many of its members and supporters view anything short of instant revolution as a disappointing anticlimax if not active betrayal.

What Cruddas terms ‘the death question’, on the party’s capacity to ‘adapt or die’ in the face of socioeconomic changes impacting its traditional voting blocs, has been a recurrent one. He recounts how the industrial working class which had thrown its weight behind Labour’s forward march in the early 20th century then underwent its own changes in status and identity – due, partly, to the social mobility enabled by Labour’s own achievements in office, including rising wages, job security and the settlement of the welfare state. After the party’s defeat to Winston Churchill’s Conservatives in 1951, this debate fed into more libertarian forms of socialism and the emergence of the New Left, and was renewed under Neil Kinnock’s battles with wider liberation movements and the party’s left as Thatcherism enacted its own targeted assault on both working-class identity and its industrial base. New Labour’s ‘modernisation’ of the party – in fact a partial return to early 20th-century LibLabism – took place as ‘end of history’ triumphalism after the end of the Cold War suggested that a socialist alternative to the status quo was no longer either valid or necessary. As the ensuing decades of crisis, unrest and instability have gone on to thoroughly debunk this suggestion, so the persistent question of Labour’s purpose – as a vehicle for ameliorated capitalism or for a wholesale transformation of it – has again become a site of struggle.

Cruddas is conscious throughout A Century of Labour of not only the importance of history to the party, but also that same history’s susceptibility to weaponisation informed by sentiment and mythologising. The party achieves most, he argues, when it channels its past traditions into active engagement with the challenges of the present. Against Labour’s historical tapestry of doctrinal clashes and larger- than-life personalities, Cruddas assesses the current leadership of Keir Starmer as oddly insubstantial when not ruthlessly self-serving, and the wisdom of its limply managerialist approach yet to be proven.

Can Labour sustain itself for another hundred years? It is worth considering this question within the larger debate on whether any party rooted in the 20th century can fully face the challenges of a world that seems to be moving increasingly further from both liberal democracy and parliamentary authority, and what new forms of representation and expression – for good or ill – this turbulence might give rise to.

-

The Wild Men: The Remarkable Story of Britain’s First Labour Government

David Torrance

Bloomsbury, 336pp, £20

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link) -

The Men of 1924: Britain’s First Labour Government

Peter Clark

Haus, 296pp, £20

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link) -

A Century of Labour

Jon Cruddas

Polity, 288pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Rhian E. Jones writes on history and politics. Her latest book, with Matthew Brown, is Paint Your Town Red: How Preston Took Back Control and Your Town Can Too (Repeater, 2021).