‘The Extraordinary Journey of David Ingram’ by Dean Snow review

Great cities more than a mile long, ‘banquette houses’, elephants, and birds with heads ‘as big as a man’s: the journey of David Ingram.

In August 1582 an English sailor, David Ingram, sat before a panel of gentlemen who were very interested in what he had to say. The men included Queen Elizabeth I’s principal secretary, Sir Francis Walsingham, and the wealthy Catholic investor Sir George Peckham. Both were gathering information on whether colonisation of the ‘New World’ could be successful; Ingram, unlike the rest of the room, had actually been to North America.

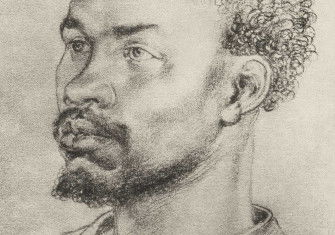

He also had an incredible story to tell, retold in Dean Snow’s new book. Ingram had joined Sir John Hawkins’ third slaving expedition, which left Plymouth on 2 October 1567. They spent two months on the Guinean coast and departed from what is now Freetown in Sierra Leone on 3 February 1568. After a few months in the Caribbean Sea, stopping at various islands and coastal towns in what is now Venezuela and Colombia, they made their way between the Yucatán Peninsula and Cuba in order to pass out of the Gulf of Mexico and through the Strait of Florida back into the Atlantic.

They did not make it. In September, a fierce hurricane forced the fleet to take harbour at the hostile Spanish port of San Juan de Ulua at Veracruz on the Mexican coast. A deadly battle ensued, and half of Hawkins’ fleet were killed or captured. Once they were out of immediate danger, Hawkins told the remaining men that they had a difficult choice to make: they only had the provisions to keep half the crew alive for their journey across the Atlantic.

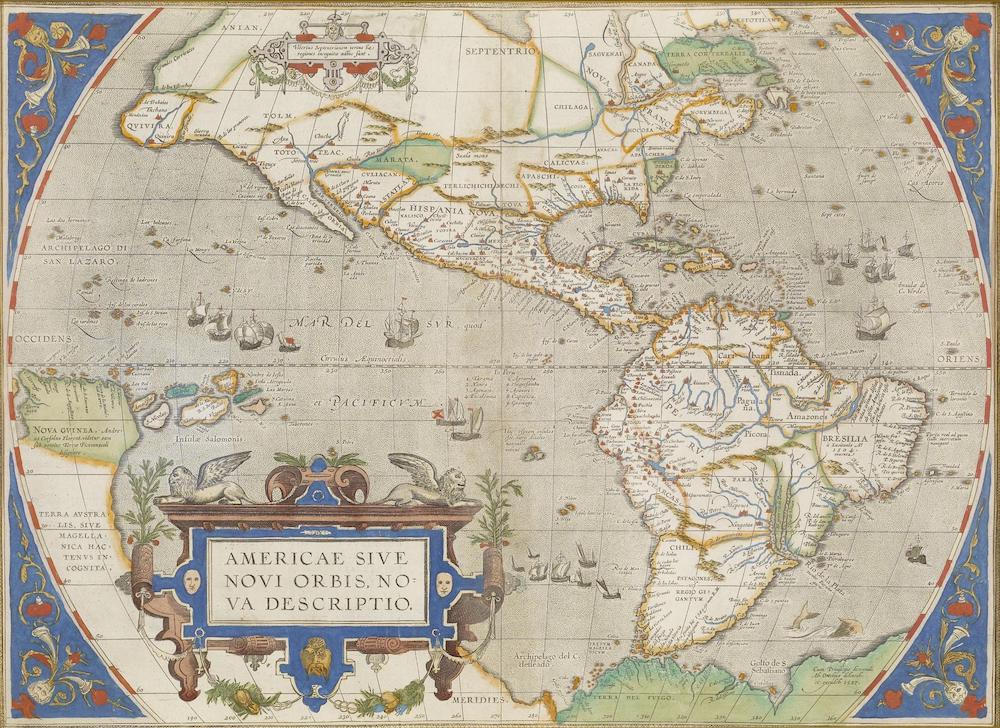

In October 1568, David Ingram was one of 112 men left on the shore of Tampico, Mexico, then the coastal territory of the Huastecs. Eleven months later, Ingram and two other survivors, Richard Browne and Richard Twide, were rescued, thousands of miles away, at the mouth of the Saint John River on the Bay of Fundy in Canada. The only record of their experiences are Ingram’s responses to the questions from his 1582 interrogation.

A version of what he said was printed by Richard Hakluyt in his Principall Navigations of 1589 where ‘the Relation of David Ingram’ described the people, lands, flora and fauna that he had encountered. The ‘relation’ claimed that Ingram had seen great cities more than a mile long, ‘banquette houses’, exotic plants, elephants, and enormous birds with heads and thighs ‘as big as a man’s’. Ingram’s relation was left out of Hakluyt’s much expanded second edition of 1598-1600, and Samuel Purchas explained this omission in 1625 as the result of ‘some incredibilities of his reports’. Ingram’s fate as a notorious liar was sealed. The majority of subsequent commentators (Snow included) dismissed Ingram as having concocted an imaginary fairyland out of his experiences in America. And yet, to quote Snow: ‘Scholars should admit their mistakes, especially when they are repeated.’

Snow has returned to the original manuscripts and reconsidered Ingram’s account. Utilising his expertise in the anthropology and archaeology of North America, Snow has meticulously reconstructed Ingram’s 3,600-mile journey along known 16th-century indigenous trails, and has also proved that everything Ingram said to his interrogators was true to the best of his knowledge and ability. Anything in his testimony that appears erroneous or fantastical was a result of being questioned by men who were totally ignorant of America and who did not realise that Ingram was commenting on his entire voyage, which included time in Africa (hence the elephants) and the Caribbean (where he would have seen the man-sized harpy eagle, entirely unknown in 1582). Ingram was poorly recorded by the scribes and unfairly edited by Hakluyt.

The challenges of writing this book were monumental, restricted by the questions Ingram was asked. Snow stretches the limits of this material in ways that are at times speculative, but compelling. He also uncovers new evidence about indigenous North America. For example, Ingram visited a well-established northern Iroquoian town, Balma, in spring 1569, some six years earlier than the current estimate for the first known Susquehannock community in southern Pennsylvania. It was here that Ingram saw the longhouses complete with long interior benches that prompted him to refer to them as ‘banquette’ houses.

This fascinating book will frustrate some readers. The manuscript is scattered with typos from the second line of the preface, and is occasionally repetitive (we read twice the postscript that supposedly offered inspiration for Shakespeare’s Tempest, despite it only appearing in the unreliable Hakluyt version of Ingram’s story). Much of what is frustrating, however, is beyond Snow’s control. We will never have a sense of Ingram’s own emotional state on his journey, or of the bonds he must have made with his two surviving companions. Snow makes the persuasive case that they may have learnt native American sign language to trade with the peoples they met, but we cannot know for sure. We only get the tiniest glimpse into Ingram’s personality when he explains that he enjoyed the scent of the aromatic peat he encountered in West Africa so much that he made a ‘ball for its delicate smell, and tied it to his hair, hanging down over his nose’.

What kind of reception Ingram received on his return is also disappointingly mysterious. He seems to have carried on with life as normal. Snow has tracked him down, finding him on Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s final colonising mission which departed from Plymouth for Newfoundland on 11 June 1583, and in which Gilbert (half-brother of Sir Walter Ralegh) had tried, and failed, to claim the island in the queen’s name. Ingram was possibly one of the last people to see Gilbert alive, the prevailing theory being that, after assaulting a cabin boy, Gilbert was cast adrift on a ship without provisions and left to die. But this, and so much else, remains uncertain.

The Extraordinary Journey of David Ingram: An Elizabethan Sailor in Native North America

Dean Snow

Oxford University Press, 336pp, £19.99

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Emilie Murphy is Lecturer in Early Modern History at the University of York.