Fashion and the Third Reich

Fronted by Magda Goebbels, the Deutsches Modeamt was an attempt by the Nazis to put the fascist into German fashion.

One of the more surprising aspects of Hitler’s arrival in power in 1933 was the foundation of a German Fashion Institute. Known as the Deutsches Modeamt, it was a reflection of Nazi attempts to control every aspect of women’s lives, including what they wore.

Hitler was an unlikely fashionista – despite overseeing the uniform for the Bund Deutsche Mädel, his approach to feminine adornment was generally negative. He hated make-up – often remarking that lipstick was composed of animal waste – and disapproved of hair dye. Perfume disgusted him, though he bowed to Eva Braun’s enthusiasm for it, and smoking was revolting. Trousers were out, too, as unfeminine, and fur was horrific because it involved killing animals. Yet he displayed a typical ambivalence about fashion, proclaiming that ‘Berlin women must become the best dressed in Europe’, and claiming ‘what I like best of all is to dine with a pretty woman.’

In essence the Deutsches Modeamt, established with full governmental support, existed to put the fascist into fashion. Women would wear only clothes made by German designers, with German materials. German, of course, meant Aryan, which knocked out the vast majority of the existing textile trade and high society designers. An organisation called the Association of Aryan Clothing Manufacturers quickly sprung up, with its own label to be sewn into garments, guaranteeing that they had only been touched by Aryan hands. The image promoted by the Institute celebrated tradition, making dirndls, bodices and Tyrolean jackets all the rage. Wearing Tracht, a regional folk costume, came to symbolise Völkish spirit. But more important even than this, was Hitler’s desire to extinguish French influence in the German fashion industry. He hated Paris fashion, firstly because it was French but also because the styles pioneered by designers like Chanel encouraged an unnaturally slender silhouette. A nation of women striving for slim hips and boyish bodies was certainly not ideal if you wanted to encourage prolific child-bearing. ‘No more Paris models,’ he announced in June 1933.

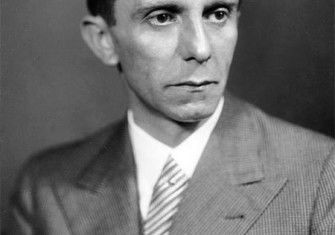

One of the richest ironies of the Reich Fashion Institute, and the one which made it such an irresistible subject for a novelist, was the choice of Magda Goebbels, wife of the Propaganda Minister, as honorary president. Like many other aspects of Third Reich, her participation was rife with contradictions. The chain smoking, Elizabeth Arden-coated Magda adored couture. Her favourite designers, Paul Kuhnen, Richard Goetz and Fritz Grünfeld, were Jewish. She wore hand-made Ferragamo shoes. The other senior Nazi wives, especially Annelies von Ribbentrop and Inge Ley, wife of the Labour leader Robert Ley, had similar tastes. Magda attempted to modify the ‘Gretchen’ image of the Fashion Institute by musing publicly that ‘the German woman of the future should be stylish, beautiful and intelligent’. It may have been this attempt to change the face of Nazi chic which led her husband to sack her from the Deutsches Modeamt later in 1933, but the Institute itself lived on until 1944, an unlikely instance of the perverted politics of fashion.