‘The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover’ by Lerone A. Martin review

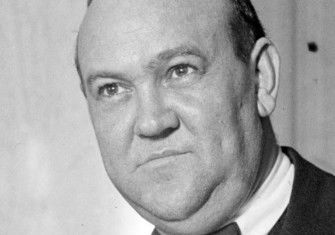

J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI from 1924 to 1972, thought the Bureau’s mission was to defeat the godless forces of liberalism, feminism and civil rights.

J. Edgar Hoover believed the United States was God’s chosen nation. Hoover, who was director of the FBI from 1924 to 1972, thought the Bureau’s mission was to defeat the godless forces of liberalism, feminism and civil rights. In Hoover’s view, to overcome these foes America had to yield to his preferred brand of Christianity – a Christianity unerringly conservative, patriotic and white.

The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover demonstrates how the FBI director infamous for persecuting Martin Luther King worked systematically to champion his own religion. Using thousands of newly declassified FBI documents, Martin describes how Hoover bent the culture of the FBI, and collaborated with famous evangelicals and Catholics to try to establish his Christian America. Together they fomented the political rise of white Christian nationalism, with vast implications for electoral politics, the concept of national security, and the role of race and religion in US identity.

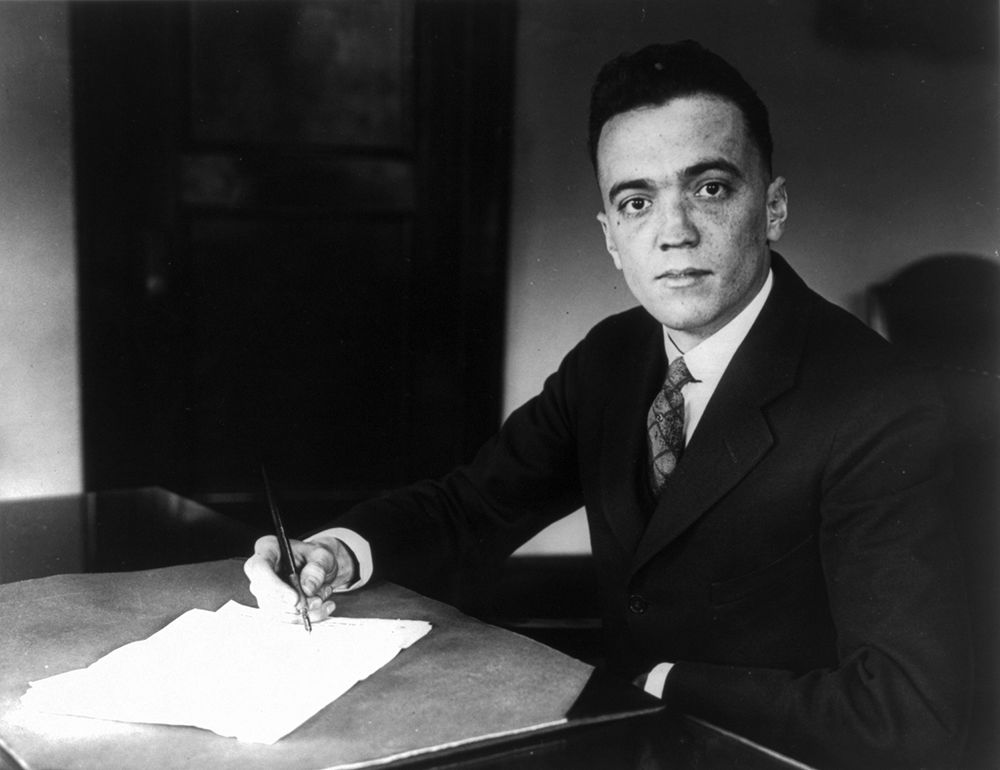

Hoover had been devout since boyhood. Born in Washington, D.C. in 1895, he volunteered as a Sunday School teacher and prided himself on his knowledge of Scripture. Before his father fell ill, and it became necessary for him to choose higher-paying employment, the young Hoover had intended on becoming a Christian minister. Instead he studied law, worked in the Department of Justice and, aged just 29, was appointed to lead the FBI.

As ‘America’s top cop’, Hoover turned the FBI into a blend of a Sunday School, a private-members club, and a white supremacist clique. He demoted all non-white special agents, as well as most of their Jewish counterparts, and made Christianity part of FBI training and social events. In contrast to the fiercely anti-Catholic sentiment in much of US society, Hoover respected orthodox Catholicism for its moral and theological rigour. He welcomed Catholicism into the Bureau, instigating an annual FBI Mass and an annual Jesuit spiritual retreat for all agents, regardless of their religion.

Outside the Bureau, Hoover launched a public relations campaign. Most significant were his essays in the conservative magazine Christianity Today, which were wildly popular and led parishioners to write to the director with their moral, theological and patriotic concerns. The pre-eminent Catholic televangelist Fulton Sheen praised the FBI, and the evangelical preacher Billy Graham regularly quoted Hoover in his sermons. Other clergy simply stood at the pulpit and read essays he had written.

Throughout, Hoover sought to maintain his reputation as an upstanding member of the establishment. He collaborated with the ‘respectable’ congregations in Washington and arranged for Methodists to host the FBI at several segregated churches. In gratitude for doing God’s work, the United Methodists built a church on Hoover’s birth site and consecrated a 33-ft stained glass named ‘THE J. EDGAR HOOVER WINDOW’.

Hoover’s actions were regularly unconstitutional. Lerone Martin tells us that from 1956 to 1971 Hoover sanctioned ‘at least two thousand illegal direct actions targeting domestic civic organizations – clergy, students, advocates of civil rights, proponents of women’s rights, and anti-war protestors’. Some of his religious operations were both unconstitutional and bizarre, such as when he launched an investigation into a new translation of the Bible. The Revised Standard Version (1952) correctly rendered a word from Isaiah that Christians believe refers to Mary, mother of Jesus, as a young woman rather than virgin. Hoover, however, saw the translation as part of a communist plot to undermine America’s Christian values, and included mention of the ‘Red Bible’ in a training manual for Air Force reservists, where it was labelled as a book to be eliminated.

From Hoover’s petty squabbling over biblical disputes to his flagrant abuse of the separation of church and state, the details in Martin’s book are astonishing. Some episodes, however, are bloated by too much signposting or ancillary information. We don’t need to know what the FBI ate for breakfast after their annual Mass – what is much more interesting is that in a constitutionally secular country, the meal was subsidised by the state.

Still, The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover is a fine work of scholarship that displays a diligent use of archives and a relentless pursuit of the truth. The FBI were unsympathetic to Martin’s project, and he had to sue the Bureau for not responding to a Freedom of Information request. Even then, Martin writes, ‘the Bureau did not concede breaking the law’ and ‘would not disclose or even acknowledge the existence of any records concerning Billy Graham and his relationship to law enforcement or national security’.

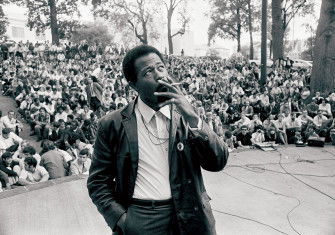

Martin points out that the FBI remains cast in Hoover’s mould. The Bureau has been too slow to combat the security threat posed by white Christian nationalists – a nativist community implicated in violent, terrorist attacks, including the insurrection of 6 January 2021. Both white Christian nationalism and the FBI’s inertia are part of Hoover’s legacy – the legacy of a man who believed himself, and his religion, to be above the law.

The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover: How the FBI Aided and Abetted the Rise of White Christian Nationalism

Lerone A. Martin

Princeton University Press, 352pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Daniel Rey is a writer and critic based in New York.