A History of Opium

Opium has been known and used for more than 7,000 years. A brilliantly researched and wide-ranging study brings its history up to date.

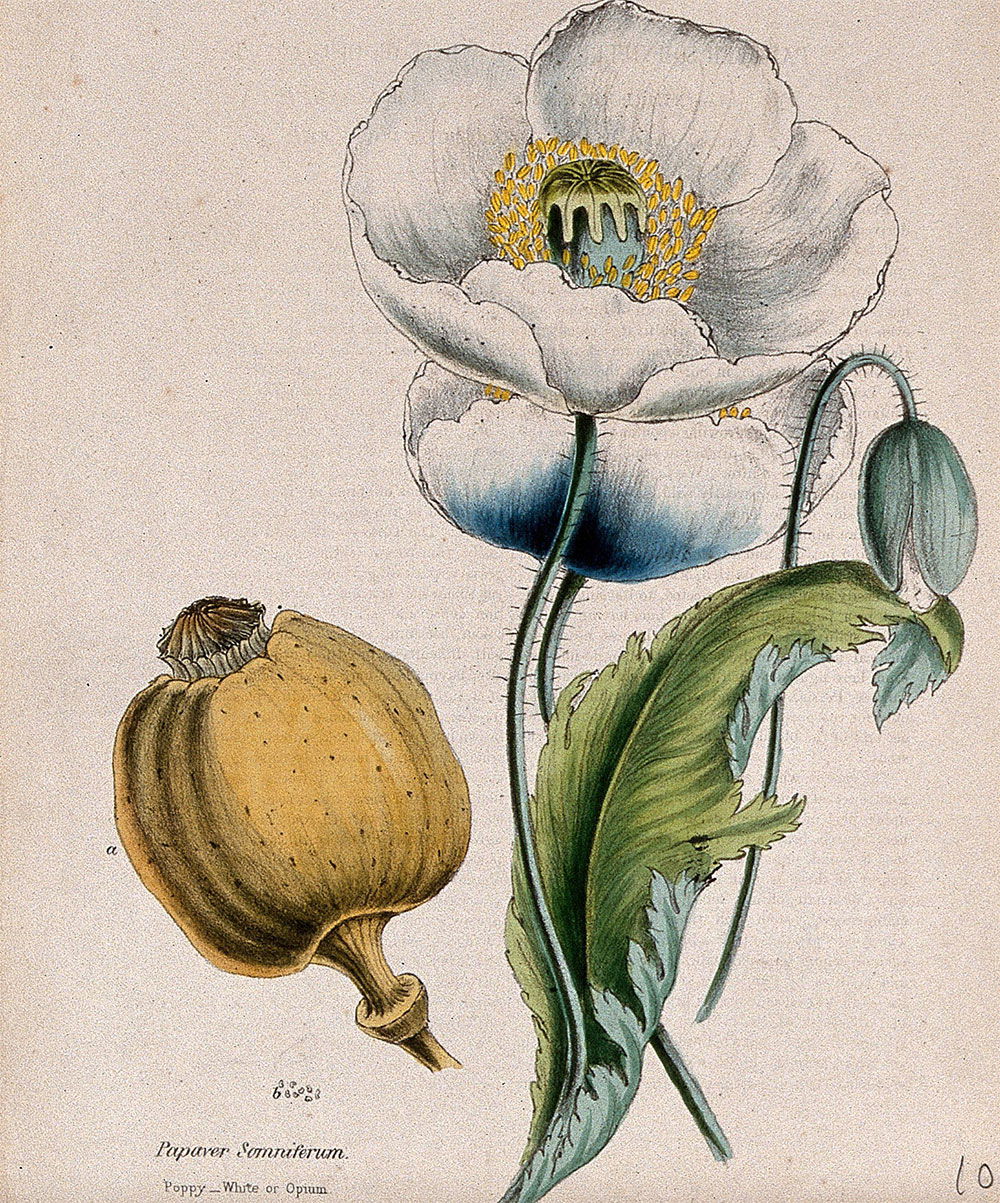

No one knows exactly when opium was discovered. Early evidence of its consumption was found in a Neolithic burial site near Barcelona, where it appears it was used for its narcotic and analgesic effects. The ancient Greeks, who held the opium poppy sacred, claimed it was Demeter who discovered it, with figurines of Poppy goddesses found in Gazi, Crete. Lucy Inglis shows us how widespread its use was in all its forms, from poppy seeds to morphine and heroin.

No one knows exactly when opium was discovered. Early evidence of its consumption was found in a Neolithic burial site near Barcelona, where it appears it was used for its narcotic and analgesic effects. The ancient Greeks, who held the opium poppy sacred, claimed it was Demeter who discovered it, with figurines of Poppy goddesses found in Gazi, Crete. Lucy Inglis shows us how widespread its use was in all its forms, from poppy seeds to morphine and heroin.

We do not just learn about opium, however; Inglis’ book informs us about immigration, disease, trade, missionaries, racism, Opium Wars, the Gin Craze, addiction and the multifarious subjects which contribute to its history. Even the Crusades and Marco Polo get a mention. This highly informative exploration of the history of opium (and the world, it would seem) sweeps from the prehistoric to modern recreational use.

New medical uses of opium were found by various Arab scholars who contributed to developments in anaesthesia, analgesia, pharmacology and surgery. In Baghdad, opium was being used in pills and as an ointment to treat diseases, including leprosy. The Basra physician al-Kindi drew up a valuable list of the correct amount of medicinal opium to administer, while the better-known al-Razi was possibly the first physician to use opium as a general anaesthetic.

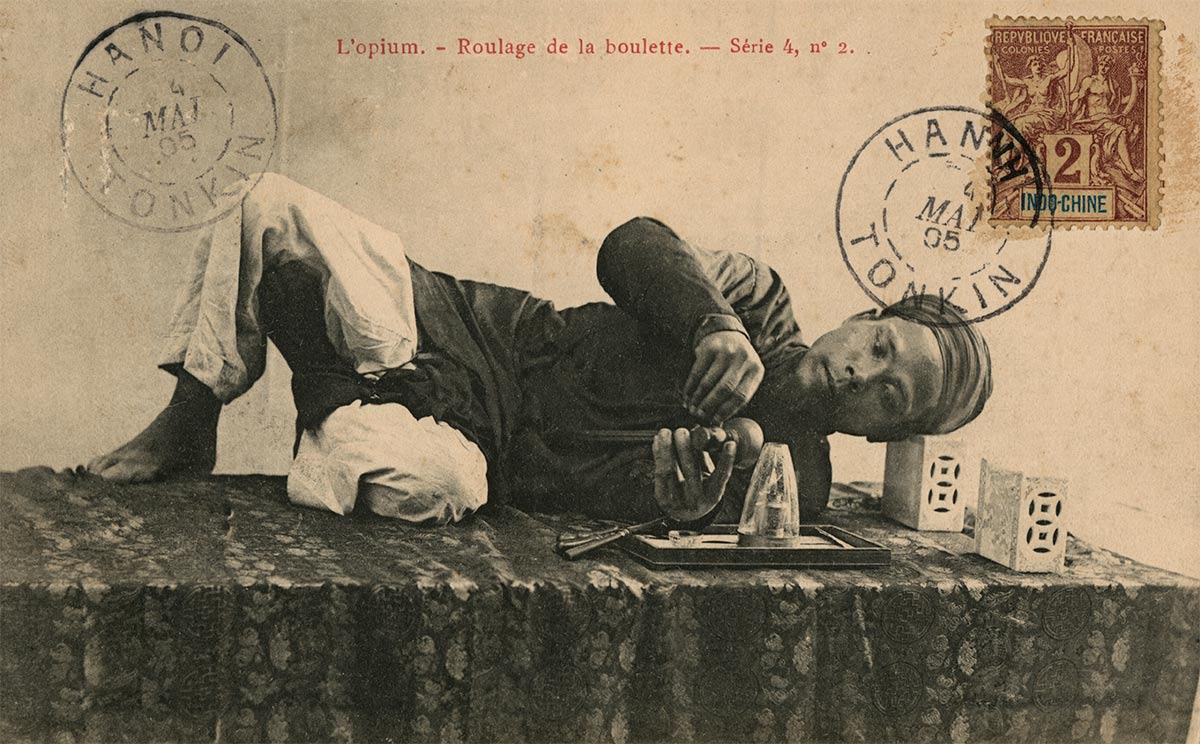

By the Age of Discovery, the plague had killed millions of people in Europe and opium was reintroduced as a method to protect and treat wealthy patients. Recreational use of the drug was taken up enthusiastically by the citizens of the Persian Empire during the late medieval period. Rulers of the Mughal Empire formed opium habits by eating it; Emperor Jahangir was so inebriated on the drug and wine it left him incapable of ruling. His wife had to fill his role. In Turkey, its use was so widespread, it was said: ‘There is no Turk who would not buy opium with his last penny.’

In 1676, physician Thomas Sydenham made perhaps the biggest impact on society by publishing his recipe for laudanum, sharing his discovery worldwide. As Inglis points out, ‘Opium, through the old manuals, apothecary shops, and increasingly through laudanum, paregoric and Dover’s powder, had found itself a place in almost every home.’ It was so well-liked that it was used for ailments until after the Second World War.

The side-effects of laudanum were expanded upon by surgeon George Young, who wrote in 1753: ‘Everybody knows a large dose of laudanum will kill, so need not be cautioned on that head; but there are few who consider it a slow poison, though it certainly is.’ Its addictive qualities were noticed particularly in women, who, according to French doctor J. Hector St John de Crèvecœur, were ‘taking a dose of opium every morning, and so deep-rooted is it that they would be at a loss how to live without this indulgence’.

A heroin epidemic hit Chicago in the late 1940s, mainly affecting poor black communities. Writers Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and others of the Beat Generation experimented with it; the most notorious anecdote relates to a drug-induced William S. Burroughs accidentally shooting – and killing – his wife in a game of William Tell. He became addicted, but his drug-fuelled novels Junkie (1953) and The Naked Lunch (1959) became classics.

Tracking any subject matter throughout such a broad timespan is difficult. Yet Inglis has graced her pages with tales and medical snippets to provide enough information to feed a small library. This must be opium’s definitive history.

Milk of Paradise: A History of Opium

Lucy Inglis

Pan Macmillan

464pp £25

Julie Peakman’s books include Amatory Pleasures: Explorations in Eighteenth-Century Sexual Culture (Bloomsbury, 2016).