Marshalsea: The Worst Prison in the Country

Marshalsea Debtors' Prison became a microcosm of society.

Biography is something we associate with ‘great figures’ of history: generals, politicians, writers, artists and reformers. Rarely is the form used for an institution, particularly one which housed many people on the edge of society. Mansions of Misery cleverly weaves individual tales of impoverishment into the general tapestry of London life in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Some chapters focus on the debtor experiences of notable inmates, such as the musician John Grano, who inhabited the Marshalsea in the 1720s, and Charles Dickens’ own father John, who served a spell almost 100 years later. These two figures roughly mark the beginning and end of the story, allowing for in-depth descriptions of two similar, but at the same time very different, experiences. The surrounding narrative is made up of smaller personal accounts, interspersed with the legal and political developments relating to debt relief and regulation. This paints a clear picture of how the Marshalsea evolved over time and the different types of people who came into contact with ‘the worst prison in the country’. Included in these fascinating vignettes are the optician Joshua Reeve Lowe, who had saved Queen Victoria from assassination, and the noted swindler James Stamp Sutton Cooke.

Biography is something we associate with ‘great figures’ of history: generals, politicians, writers, artists and reformers. Rarely is the form used for an institution, particularly one which housed many people on the edge of society. Mansions of Misery cleverly weaves individual tales of impoverishment into the general tapestry of London life in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Some chapters focus on the debtor experiences of notable inmates, such as the musician John Grano, who inhabited the Marshalsea in the 1720s, and Charles Dickens’ own father John, who served a spell almost 100 years later. These two figures roughly mark the beginning and end of the story, allowing for in-depth descriptions of two similar, but at the same time very different, experiences. The surrounding narrative is made up of smaller personal accounts, interspersed with the legal and political developments relating to debt relief and regulation. This paints a clear picture of how the Marshalsea evolved over time and the different types of people who came into contact with ‘the worst prison in the country’. Included in these fascinating vignettes are the optician Joshua Reeve Lowe, who had saved Queen Victoria from assassination, and the noted swindler James Stamp Sutton Cooke.

The real strength of this book is undoubtedly the way the author brings to life the daily struggles of the debtor’s world, as well as the often questionable actions of those enforcing the rule of law. Anecdotal accounts, such as bailiffs trying to arrest the body of a deceased debtor, are plentiful, as well as examples of unscrupulous creditors abusing ‘mesne process’ to arrest debtors, some as young as four, without having to prove it in court. There is a comprehensive analysis of the ruthless ways in which everyone from simple turnkeys, charged with the day to day running of the prison, to notorious deputy marshals, such as William Acton, ‘skinned the flint’ in order to exploit the inmates for profit. The work is very even-handed, with plenty of instances of right and wrong on both sides of the economic divide.

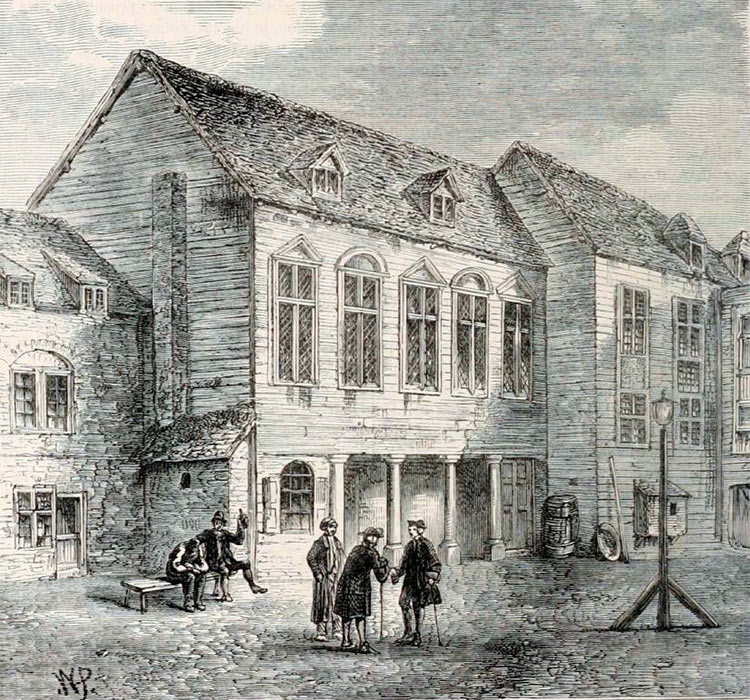

The prison itself is richly described in detail, cleverly depicted as a microcosm of society: from the Common side, where the poor were housed, to the Master’s side, for those of greater means such as Grano, who often survived on aid from long-suffering friends and family. There was a surprisingly large range of amenities on site, including an alehouse, coffee shop, chandlery, chapel and space and equipment for sports and recreations. Codes of conduct evolved, with new prisoners being forced to pay ‘a garnish’ and disputes being dealt with by a sophisticated system of prisoner-run government. Mansions of Misery is altogether a well-paced and informative work that deals with a weighty subject in an objective and stimulating way.

Mansions of Misery: A Biography of the Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison

Jerry White

The Bodley Head 364pp £20

Stewart Tolley is a part-time tutor for Oxford University’s Continuing Education Department. He researches the representation of politics in the early 18th-century press.