Nagorno-Karabakh’s Myth of Ancient Hatreds

The Nagorno-Karabakh dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan is sometimes explained as a result of ‘ancient hatreds’. In reality, it is nothing of the sort.

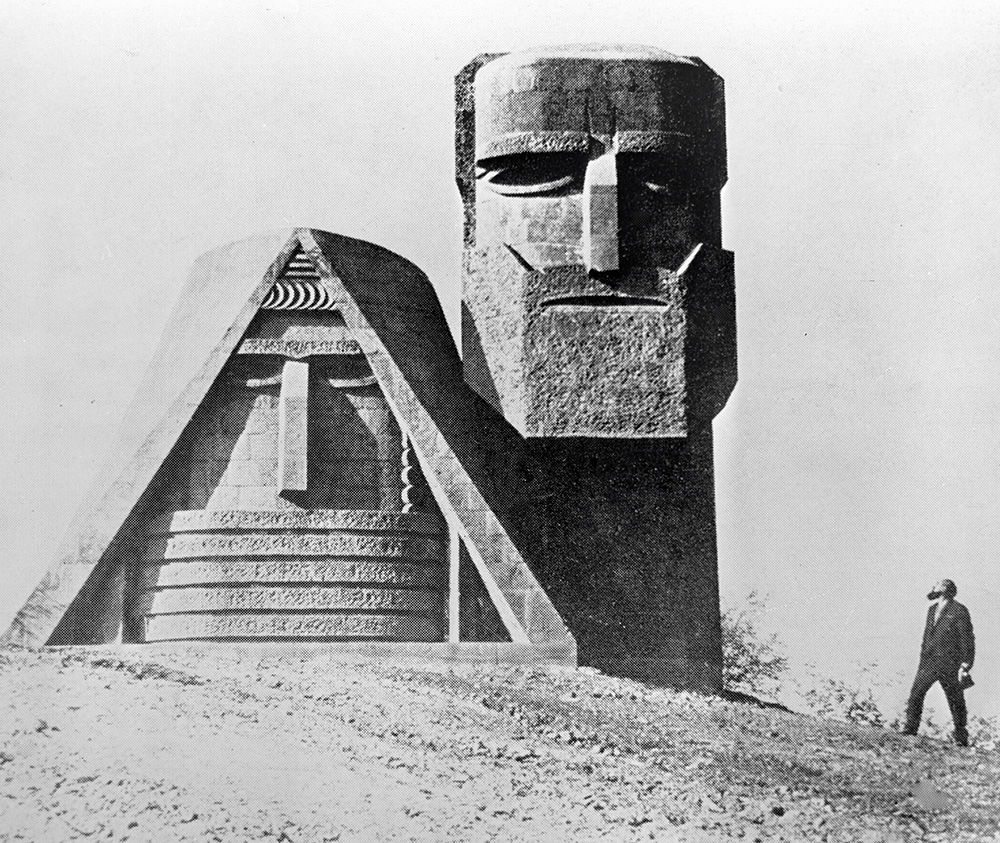

Mountain range near Stepanakert, 2018.

During the last week of September, an Azerbaijani offensive re-ignited a decades-old conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh (‘Mountainous Karabakh’) region. Within a week, the conflict had escalated beyond the ‘line of contact’ dividing Armenian and Azerbaijani forces. Stepanakert, the capital of the unrecognised Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, has sustained heavy shelling, with Amnesty International condemning the use of cluster munitions. Armenia has struck targets in Azerbaijan beyond the contested Karabakh region and civilians as well as soldiers have lost their lives in the most prolonged violence since the 1994 ceasefire. These events differ from previous flare-ups, not only in intensity but in the direct Turkish support for Azerbaijan, including the country’s widely reported recruitment of mercenaries from Syria.

Nagorno-Karabakh (to Armenians, Artsakh) is a highland region located between the states of Armenia and Azerbaijan. Historically, the majority of its population has been Armenians, but it has deep geographical, cultural and economic connections with the lowlands of Azerbaijan. When conflict broke out here at the end of the 1980s, ‘ancient hatreds’ proved to be a tempting explanatory framework for some observers. While this trope is still sometimes evident, there is scant historical evidence to support it. This is a distinctly modern conflict, with groundwork laid not in the ancient past, but during the creation of Soviet states in the South Caucasus. In particular, the decision in 1921 to incorporate the region into Soviet Azerbaijan rather than Soviet Armenia has been identified as pivotal. This is certainly true, but a focus on poor decision-making by the Soviet political elite should not preclude examining longer-term contexts and processes.

During the 19th century the demographic balance of the Caucasus was changed by shifting imperial borders and population resettlements, increasing overall Armenian presence. Though the region remained a multi-ethnic space, the influence of European discourses of nationalism meant that its intermingled populations increasingly saw their futures in national terms. Modernisation created new tensions and inequalities which often played out along ethnic lines. In 1905 the city of Baku became the centre of widespread clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis (in Russian imperial terminology, Tatars). From 1914, war and the Armenian Genocide led to cycles of violence and displacement across the region. In the aftermath of imperial collapse and revolution, Georgians, Armenians and Azerbaijanis each tried to carve out distinct national spaces for themselves. Karabakh was one of several localities where this led to violence.

Soviet rule accelerated the transformation of the South Caucasus into national spaces. Soviet policies encouraged the construction of nations among former subject peoples of the Russian Empire as the first step on the long road to socialism. They included the promotion of national languages and cultures, the fixing of personal identities in passports and the definition of borders. These policies were underpinned by the principle that the world could and should be divided into discrete national groups, which belonged in clearly defined territories. The reality on the ground in the South Caucasus – mobile, intermingled populations and overlapping attachments to territory – was not easily aligned with this territorialised vision of nationality. The designation of Nagorno-Karabakh as a clearly defined autonomous oblast (region) within an Azerbaijani Soviet Republic was an attempt to square this circle.

Under Soviet rule for seven decades, Armenians and Azerbaijanis maintained largely peaceful, if not always harmonious, relations. Each republic was home to significant minorities of the other nationality, but the successful Soviet cultivation of national identities in the South Caucasus meant that Karabakh’s status appeared ever more anomalous and Karabakh Armenians intermittently petitioned for unification with Armenia. Social and economic grievances in the region could increasingly be framed in national terms: in 1988, in the context of glasnost and perestroika, widespread demonstrations were held in both Karabakh and Armenia. The Armenian-dominated Karabakh Soviet made a formal request for unification with Armenia. Though rejected, this prompted anger and insecurity in Azerbaijan. Violence followed swiftly. Attacks on Armenians in the city of Sumgait later that month left 26 Armenians and six Azerbaijanis dead.

This turn to violence is not easy to account for. Local grievances and inequalities, brought to the fore in the upheavals of the 1980s, were refracted through the prism of past violence and narratives of national belonging. Moscow’s response proved ineffective and the crisis spiralled, resulting in widespread intercommunal violence and reciprocal expulsions. The fate of Karabakh became central to national movements in Armenia and Azerbaijan. As the two republics gained independence in 1991, the conflict had become a fully-fledged war. By 1994 Armenia had effectively won the military victory, in possession not only of Nagorno-Karabakh but also the surrounding regions of Azerbaijan, from which the local Azerbaijani population were displaced. The ceasefire brought no permanent resolution. A nominally independent Nagorno-Karabakh Republic was declared, but remains unrecognised.

To locate the origins of the current conflict in the 20th century is not to suggest that deeper histories do not matter. Contemporary Armenia and Azerbaijan both claim significant historical connections to Karabakh. For Armenians, this is embodied by the presence of medieval religious architecture and the history of semi-autonomous Armenian principalities or melikdoms. In Azerbaijan, the focus is on the rich cultural history of the 18th-century khanates centred on the city of Shusha. When the war began, exclusionary narratives of national history flourished. History writing in both Armenia and Azerbaijan was characterised by attempts to trace ever deeper roots in Karabakh, and historical and archaeological evidence was marshalled to support contemporary territorial claims. The polarised narratives which emerged are pervasive, extending beyond the realm of academic debate into popular culture and mainstream political discourse.

This conflict has entered its fourth decade. While the term ‘frozen conflict’ might suggest that that the region has been in stasis since 1994, this is far from the case. Communities have been shaped by insecurity, intermittent violence and persistent fear. Conscripted soldiers have lost their lives in repeated and increasingly deadly clashes. Neither side has had a monopoly on violence or victimhood. Memories of terrible atrocities – for Armenians the Sumgait pogroms and for Azerbaijanis the massacre of hundreds of civilians at Khojaly in 1992 – are connected with past episodes of violence, imbuing them with even greater emotional resonance and reinforcing stereotypes of an unchanging enemy. Young Armenians and Azerbaijanis have lived pointedly apart from one another for decades and lack the older generations’ experience of sharing space, if not without tension, then without the descent into violence.

The open support of the Turkish government for Azerbaijan during the current war has, for Armenians, heightened the connection between these events and the Armenian Genocide. This has been made explicit in speeches by Armenia’s Prime Minister, Nikol Pashinyan. Different contexts, actors and agendas are now at work to those which shaped the fate of the Ottoman Armenians in 1915, but, in the context of continued Turkish denial of genocide, it is not difficult to understand why the current violence is understood by Armenians as an existential threat. A different set of painful memories shape Azerbaijani perspectives; the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis, in particular from the regions surrounding Karabakh, during the last years of the war. Reclamation of these territories and the possibility of returning refugees provide a powerful rallying cry.

For Azerbaijan, resolution depends on the return of Karabakh and surrounding occupied regions, with some provision of autonomy for Karabakh Armenians. For Armenia, ensuring self-determination for Karabakh is paramount and the resumption of Azerbaijan rule over the region is viewed as an unacceptable threat. Since 1992 the OSCE Minsk Group led by France, Russia and the USA has provided the framework for peace negotiations, with little success. Armenia’s ‘Velvet Revolution’ in 2018 ushered in a more democratic administration; hopes were raised for reinvigorated negotiations but progress quickly faltered, and by July 2020 there were new clashes on the ‘line of contact’. Resulting Azerbaijani losses were met with large anti-Armenian demonstrations in Baku and there is little space for advocates of peace or compromise in the Azerbaijani political landscape. These conditions, coupled with the apparent disengagement of the wider world, make peace appear a distant prospect.

Jo Laycock is Senior Lecturer in Modern History at the University of Manchester and the co-editor of Aid to Armenia: Humanitarianism and Intervention from the 1890s to the Present (Manchester University Press, 2020).