Nero Versus the Christians

Was Nero the Antichrist? The bestial image of the Roman emperor as the enemy of Christians persists, but the truth is more complex.

Mary Stocks, scholar, political activist, writer and journalist, published a play in 1933, provocatively titled Hail Nero! A Reinterpretation of History in Three Acts. It presents the notorious emperor (who reigned AD 54 to 68) as a figure driven by his concern for social justice and women’s rights. Stocks’ Nero sets up a resort at Antium near Rome for the common people, tries to combat disease in the slums and champions the female scientist Locusta, a woman whom others wrongly thought was a prolific poisoner. The published version of the play included a preface written by Mary’s husband John, then Professor of Philosophy at the University of Manchester, which explained the reasons for writing such a story about an emperor traditionally viewed as a murderer, arsonist and political tyrant:

In those days [antiquity] the historical conscience and the law of libel were both young and weak ... it is not beyond the resources of modern scholarship to restore even Nero to respectable company … The author of this drama uses the privileges of the imagination to carry the restoration a stage further.

While Mary Stocks may have taken full advantage of dramatic licence in her play, her instincts were correct in terms of second-guessing prevailing narratives about complex and distant historical figures. In recent decades, scholars have been doing just that.

One aspect of Nero’s legacy that has not been challenged in ancient history scholarship or popular culture until recently, however, is the belief that biblical writers thought he would return as the Antichrist. From the third to the 21st century, albeit with its popularity waxing and waning, the view that Nero is documented in the Bible as the instigator of the apocalypse has appeared in a wide variety of literature, from sermons to novels to scholarship. The story goes that the writers of books that would go on to make up the New Testament had Nero in mind when describing the adversary of Christ, the Antichrist. Two texts in particular are commonly cited: the first, Paul’s second letter to the Thessalonians (now thought by some modern scholars to have been written, after Paul’s death, by a different author) in which the Antichrist figure is the ‘man of lawlessness’; and the second, Revelation, written by John (a different John from the author of the gospel), while in exile on the island of Patmos, in which the Antichrist is the ‘first beast’. When these texts were written is debatable. In antiquity, Christians believed that 2 Thessalonians was written early in Nero’s reign, in the mid-50s, but most now agree that both texts were circulated in the latter part of the first century.

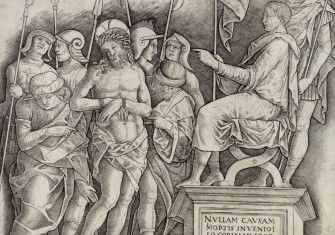

In 2 Thessalonians and Revelation, the Antichrist figure is described as cruel, violent and destructive, much as Nero is in the books we read from antiquity. Accused of killing his stepbrother, mother, wife and tutor, the historical accounts which survive, most of which date to the second century or later, are full of damning evidence about Nero’s character. In particular, he is accused of being the first emperor to kill Christians, in AD 64. In the summer of that year, ten out of Rome’s 14 districts caught fire. Fires were common in Rome, but the scale of this event was larger than usual. In the aftermath, rumours circulated that Nero himself had started the fire so that he could rebuild Rome as he saw fit. Writing in the second century, Tacitus tells us that, to put down the rumour, Nero blamed an unpopular group of outsiders in Rome, the Christians. He made a spectacle of the punishment: those convicted were killed by dogs or fastened to crosses and burned at night like lamps.

This appears to be damning evidence of Nero’s relationship with early Christians. However, in the spirit of Stocks and others, it may be wise to take a closer look at some of the precise reasons given for equating Nero with the Antichrist in Christian texts and, in particular, to reconsider what first-century perceptions of Nero were in the parts of the Empire where most Christians lived: the eastern provinces.

The son of destruction

In 2 Thessalonians, Nero is identified as the ‘man of lawlessness’, ‘the son of destruction’:

For that day will not come, unless the rebellion comes first, and the man of lawlessness is revealed, the son of destruction, who opposes and exalts himself against every so-called god or object of worship, so that he takes his seat in the temple of God, proclaiming himself to be God.

Nero’s name is never mentioned; rather, later generations of Christians, from about the third century onwards, assumed Nero was the person whom Paul had in mind when describing this destructive figure. In the late fourth century, for example, the Archbishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom, delivered a homily which confirmed to his congregation that ‘[Paul] speaks here of Nero, as if he were the type of Antichrist. For he, too, wished to be thought a god’. In a previous sermon, Chrysostom had already made his thoughts on Nero the man (and emperor) clear:

And let us prove this in the examples of two persons, Nero and Paul. The one had the glory of this world, the other the dishonour. How? The first was a tyrant … Even wise men and potentates and sovereigns trembled at him. For beside all this, he was said to be a cruel and violent man. He even wished to be thought a god, and he despised both all the idols, and the very God Who is over all. He was worshipped as a god.

Common to both of Chrysostom’s homilies is the idea that the emperor had made people worship him as a god in his own lifetime. He established this in the earlier homily and reinforced it when identifying Nero as the ‘man of lawlessness’. But how accurate is his assessment that Nero’s hubris clearly marked him out as an Antichrist-like figure? Is a claim to be divine something characteristically Neronian?

Roman emperors had been walking the fine line between mortality and divinity since Rome’s first emperor, Augustus (then Octavian), saw a comet in the sky during Caesar’s funeral games in 44 BC and declared it to be the apotheosised Julius Caesar. As Caesar’s adopted son, Augustus could describe himself as divi filius – the son of a divinity – which intimates an expectation that Augustus, too, would be made a god upon his death. In other words, many Romans saw him as akin to a divinity-in waiting. While this worked out for Augustus – he was divinised in AD 14 – the honour was not bestowed upon a dead emperor automatically. The Senate had to approve the distinction and, of Augustus’ successors before Nero, neither Tiberius nor Caligula became a divus (divinity) after their deaths. The Senate, however, did approve the divinisation of Nero’s predecessor and adopted father Claudius, meaning that Nero could make use of the title divi filius if he chose, as Augustus and Tiberius had done. References to Nero, or those he made about himself, as being related to the gods should be seen in this context. It is not an extraordinary claim to divinity.

Moreover, the specific phrase used in 2 Thessalonians – ‘he takes his seat in the temple of God’ – fits three other first-century emperors better than it does Nero. The ‘temple of God’ is the Temple in Jerusalem and it features in the biographies of Caligula, Vespasian and Titus. According to Josephus, Caligula tried to set up a statue of himself in the temple in AD 40. In the face of fierce objection from Jews at Tiberias, his friend Herod Agrippa managed to dissuade Caligula from his goal. The temple did not remain protected from Roman interference for long, though. In AD 66, war broke out in Judaea and Vespasian was sent out to deal with the rebellion. Three years later, Vespasian returned to Rome, but he left his son Titus to continue the war. In AD 70, with Vespasian now emperor in Rome, Titus sacked Jerusalem, resulting in the destruction of the temple. When decoding 2 Thessalonians’ ‘man of lawlessness’, Caligula’s hubris or Vespasian and Titus’ violent destruction seem a better fit for the description of a usurper appropriating the Temple’s sacred space.

The number of the beast

The biblical book most frequently mentioned by scholars since antiquity when considering the Nero-Antichrist is Revelation. Nero is associated with the first beast, the beast from the sea, which can be identified by the number 666:

One of its heads seemed to have a mortal wound, but its mortal wound was healed, and the whole earth marvelled as they followed the beast … This calls for wisdom: let the one who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man, and his number is 666.

John later provides further details about the beast: that it has seven heads and each of those heads is a king. Five of those kings had already reigned, the sixth is reigning while Revelation is being written and the seventh will reign only for a short time. After the seventh king has died, an eighth king will appear to bring about the apocalypse (i.e. the first beast). But the eighth will be one of the previous seven, a previous ruler who has come back to life.

As with 2 Thessalonians, Nero’s name is not mentioned in the text itself, but he became associated with the first beast in the mid-third century. Christians, such as Irenaeus in the second century, had explored the nature of the Antichrist without mentioning Nero, but the first commentator on Revelation, Victorinus of Pettau (modern Ptuj), used the emperor in his interpretation of chapters 13 and 17. When John wrote about the beast from the sea, says Victorinus, he ‘speaks of Nero’. Victorinus’ explanation caught on and, when an unknown Christian author came to discuss the Antichrist and the persecution of the Christians in the Liber genealogus, a world chronicle, in the fifth century, Victorinus was cited as one of those who recognised the true identity of the beast.

Like the beast, says Victorinus, Nero was killed by a wound to his throat: in AD 68, Nero’s freedman Epaphroditus helped the emperor to commit suicide. While this may, at first glance, seem like a compelling similarity between Nero and the beast, the focus on the location of Nero’s wound near the head is misleading. The beast’s wound in Revelation has to be in one of its heads, as each head represents the whole body of a king. This is not, then, a straightforward parallel.

Other writers, ancient and modern, have taken the number 666 to be a direct reference to Nero as it is the numerical value for Neron Kaiser (a slightly odd spelling of Nero Caesar) in Hebrew. Others have deciphered 666 to signify notorious figures from Julius Caesar to Caligula to Mussolini. Since antiquity, there has been little consensus on how the number should be decoded to reveal a name, or on which name it should reveal.

The explanation of how Nero fits into the series of seven kings is similarly fraught. This is because the identity of the king under whom John is writing, the sixth king, depends upon the date of Revelation. Some scholars suggest the sixth king, who reigned as Revelation was written, must be Domitian, because he was the first emperor after Nero to kill Christians and is therefore likely to have exiled John to Patmos. But it is virtually impossible to make Domitian the sixth king. If Augustus is the first king, as he was the first emperor, then Nero is the fifth and Galba is the sixth. If Nero is the first king, then Titus is the sixth. For Domitian to be the sixth, Galba would have to be the first king, which would mean the seven did not include Nero (and, remember, the eighth king should be one of the first seven). If we date Revelation earlier, it is possible to include Nero in the seven and place its composition during the reign of Galba or Titus. Ultimately, Revelation is sufficiently elusive that it is easy to tailor the passage to a number of interpretations. Indeed, early Christian interpreters of Revelation do not offer any explanation of how Nero fits into this sequence.

In sum, what 2 Thessalonians and Revelation provide is a list of characteristics that their readers need to decode. Some later Christians were sure the ‘right answer’ was Nero, but this is because they were used to reading the accounts of Nero’s reign recorded by historians hostile to him, which painted Nero as an out-and-out tyrant. In the late first century, however, the Jewish historian Josephus told his readers that there were many different judgements of Nero’s reign circulating. Some were complimentary, others were not. Most of these have been lost, including those that saw Nero in a more positive light. It is worth taking another look, therefore, at what sort of emperor those living during Nero’s reign would have recognised, particularly in the east of the Roman Empire, where the majority of Christians lived.

Nero in the East

To determine Nero’s reputation in the wider empire it is important to examine material evidence. For example, in Aphrodisias (Aydın Province, Turkey), visitors to a temple set up to honour Aphrodite, the divine Augustus and Augustus’ family would have seen a frieze of Nero becoming emperor in AD 54. He is displayed in military uniform and is being crowned by his mother Agrippina, who was a direct descendent of Augustus. While there may have been rumours circulating in Rome about Nero’s behaviour early on in his reign (Nero was implicated in the death of his stepbrother Britannicus in AD 55), such accounts are far less likely to have reached the other side of the Empire, where information from Rome came largely via official documents. Another frieze from the same temple reinforces the idea that Nero met the expectations of a Julio-Claudian emperor, the dynasty which was founded by Augustus. Nero is shown subjugating a personified Armenia, which recalls a similar frieze of Claudius subjugating personified Britannia. The image of Nero that the Aphrodisians encountered was of an emperor keeping up with his imperial forebears.

Similarly, in Greece, Nero’s name was, for a time, inscribed on the Parthenon at Athens. The inscription, dating to AD 61-2, describes him as the greatest Imperator (General), and the son of a god (i.e. the son of the deified Claudius). As the Parthenon was commissioned by Pericles to commemorate the victory of the Greeks over the Persians, it is likely that this rededication is also connected to a military victory in the same geographical area. At that time, Rome was fighting a war against the Parthians and it looked like the general Caesennius Paetus was enjoying early success. He would later suffer defeat, but back in Rome Nero was optimistic about the campaign and the official reports would have reflected that sentiment. Much like the Romans in Aphrodisias, then, those in Athens would have heard about Nero the Imperator waging victorious battles against Rome’s enemies.

This picture is complicated by the situation after Nero’s death. Before committing suicide, Nero was declared a public enemy by the Senate. Across the Empire, representations of him, including the friezes at Aphrodisias, were defaced or taken down. This act encouraged Romans to remember Nero’s reign as a failure. Despite this, as Edward Champlin, a leading scholar on Nero, has pointed out, images of Nero did not disappear altogether and actually continued to be created. In the mid-second century, a larger-than-lifesize statue of Nero was cut in Tralles in Asia Minor (now Aydın) and, in fifth-century Rome, Nero’s portrait was among the most popular on souvenir medals, such as those given out during the games.

Equally, it is worth revisiting the impact of Nero’s punishment of the Christians in the first century. Tacitus paints a grim picture for those blamed with arson in Rome. But would Christians outside of Rome have feared that the same treatment might be on its way to them? As Brent Shaw has recently reminded us, the often-used word ‘persecution’ in relation to Nero’s punishment of the Christians is misrepresentative. It was not a systematic action that created legal precedent, but was rather a response, albeit a brutal one, to a particular event: the fire. As such, while Christians in, say, the province of Asia (where the seven churches addressed in Revelation are located) would have been horrified by any accounts that managed to reach them, they would not necessarily have assumed they were in any danger for being Christian under Nero.

Therefore the evidence suggests there was not a widespread fear of Nero in the east in the first century. Nor are there any clear indicators in the biblical texts to imply that Nero should be the decoded identity of the beast or man of lawlessness. Had Paul or John wanted Nero to be understood incontrovertibly as the bringer of the apocalypse, stronger connections could have been made – as, indeed, happens with Antiochus IV Epiphanes in Maccabees, for example. As it is, Revelation and 2 Thessalonians can be interpreted historically in a number of ways, or can be understood metaphorically in terms of the battle between the forces of good and evil.

The Antichrist effect

Although Nero was not written into the Bible as Paul’s man of lawlessness or John’s first beast, the insistence of Christian writers from the third century that he was has left its mark. In 1892 Frederic William Farrar wrote a historical novel named Darkness and Dawn, or Scenes in the Days of Nero, the subject of which was the apocalypse as instigated by Nero. Despite being a novel, it contained footnotes in which Farrar cited early Christian writers such as Victorinus in support of the veracity of his plot. Many were struck by Farrar’s story, including the Polish novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz, who went on to write his own Neronian novel with Christians at its heart, Quo Vadis. The novel’s plot featured a mad and dangerous Nero, an emperor who ordered the death of his stepson Rufius in front of Rufius’ mother Poppea (something we do not find in the ancient sources). The novel also contained numerous references to Nero as a ‘beast’ and ‘Antichrist’. In 1951, Quo Vadis became the basis for a Hollywood blockbuster of the same name starring Peter Ustinov as Nero. The film played down the association between Nero and the Antichrist; the word is only used once in the opening voiceover of the film: ‘In this, the early summer of 64 AD, in the reign of the Antichrist known to history as the emperor Nero …’. In favour of the more theatrical side of the emperor, though, the film nevertheless exploited some of the same Antichrist stereotypes – cruelty, destruction and madness. Ustinov writes in his autobiography that, when deciding whether to accept the part of Nero in the film, he asked the director Mervyn LeRoy what he thought about Nero’s character. LeRoy answered, ‘Nero? Son of a bitch ... You know what he did to his mother?’

As Nero continued to be portrayed in film and TV, for example, by Christopher Biggins in the acclaimed BBC drama series of the 1970s, I, Claudius, and by Michael Sheen in Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire, references to the emperor as Antichrist disappeared, but scholarship has persisted in discussing the role of Nero in the Christian tradition. While many scholars still argue that Nero was intended to be understood as the Antichrist figure in the Bible, we must remember that the Nero of centuries of scholarship and literature was not the same as the Nero encountered by many Romans across the Empire during his reign. As such, we should try, as much as possible, to interpret these biblical texts with the eyes of their intended audience rather than with our own.

Shushma Malik is Lecturer in Classics at the University of Roehampton and author of The Nero-Antichrist: Founding and Fashioning a Paradigm (Cambridge, 2020).