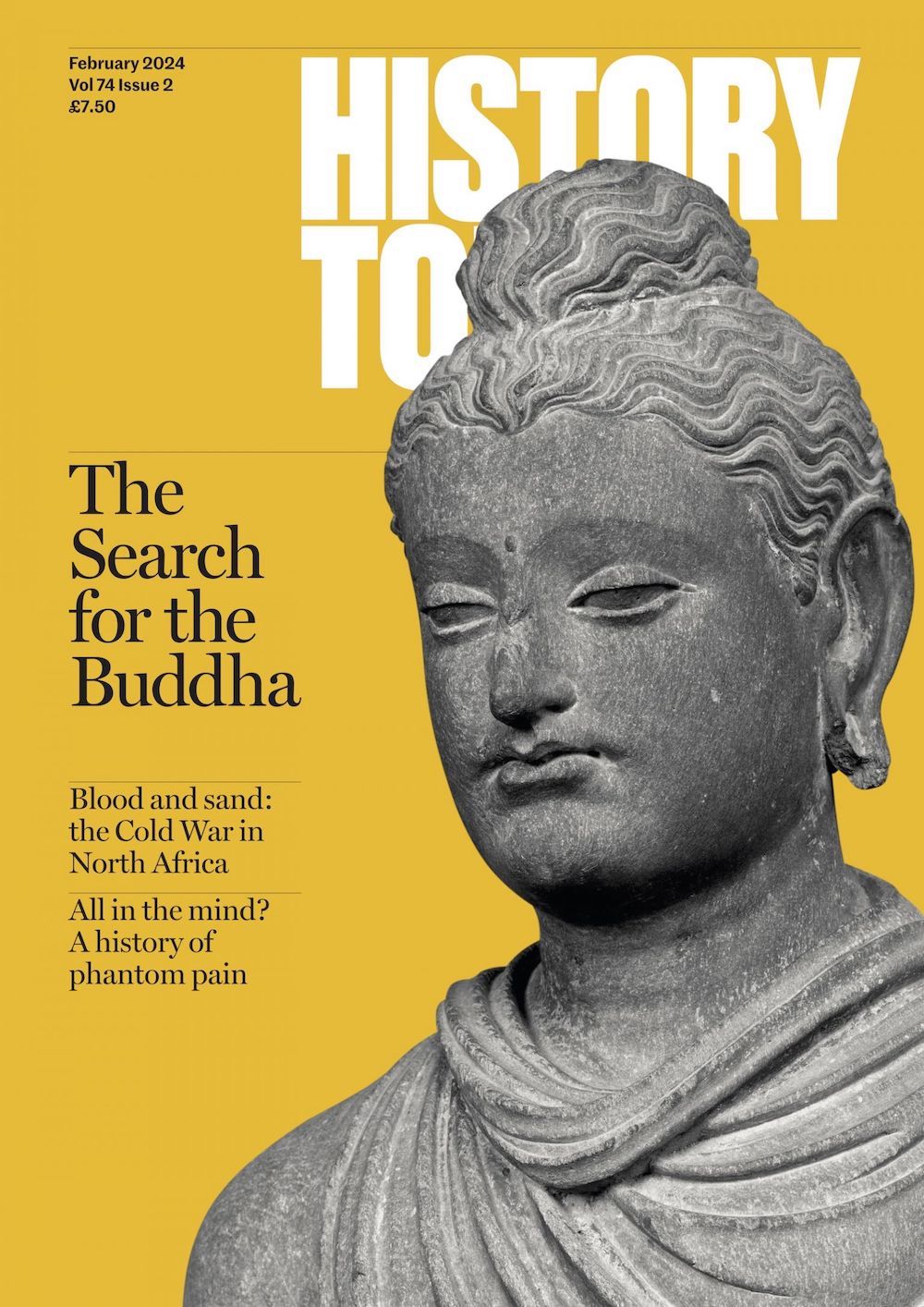

The Paris Commune’s Bloody Week

In May 1871, a short-lived Parisian revolution in social relations was brutally suppressed. What is the legacy of the Paris Commune, 150 years on?

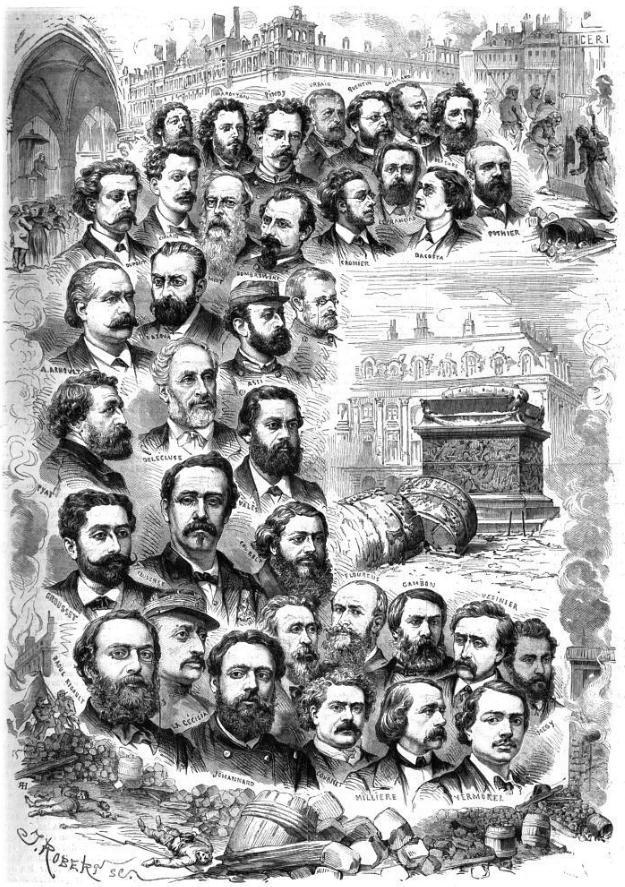

Destruction of the Vendôme Colonne during the Paris Commune, by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, 1871.

In hiding and soon to be sentenced to death in absentia, Eugène Pottier completed a poem In June 1871 that still serves as the rallying cry for the Left worldwide: L’Internationale. Its themes of solidarity and universalism would enshrine the ambitions of the Paris Commune, a brief and extraordinary social experiment that unfolded during the spring of 1871 in what was then Europe’s second-largest city. However, between 21 and 28 May, central Paris was incinerated and approximately 25,000 people massacred when French soldiers annihilated the Commune, an atrocity remembered as the ‘Bloody Week’.

The Commune’s origins lay in France’s humiliation during the Franco-Prussian War. In September 1870 Napoleon III’s Second Empire gave way to the French Third Republic, which resolved to continue fighting. Paris was besieged by Prussia and privation soon ravaged the city’s poorest districts. In January 1871 France signed an armistice with the new, Prussian-dominated German Empire. The National Assembly held elections the following month and appointed Adolphe Thiers to lead the incoming government.

A steely political navigator of France’s tumultuous 19th century, Thiers was soon rubbing salt into Parisian wounds. The wartime moratorium on debt repayments was rescinded, now requiring repayment within 48 hours, while landlords could seek arrears. This was devastating to working-class Parisians, whose industry and commerce had stalled during the war.

The National Guard (the fédérés), a militia that had expanded significantly during the siege and whose officers were elected in working-class districts such as Belleville, now posed a direct threat to bourgeois order. The aristocratic officer corps of the professional army considered them a dangerous rabble, particularly as the fédérés were determined to keep their cannons in areas like Montmartre.

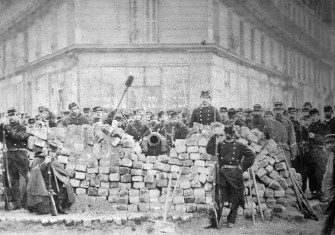

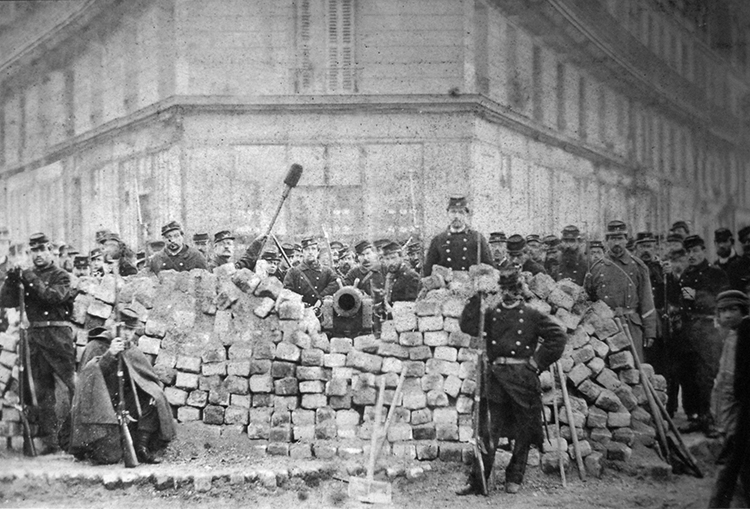

Matters came to a head on 18 March when the army attempted to confiscate them. Confronted by fédérés and local residents, many professional soldiers defected, while generals Jacques Léon Clément-Thomas and Claude Lecomte were seized and summarily executed. As barricades went up across Paris, Thiers gave orders for the National Assembly and army to abandon the capital for Versailles. In their wake, fédérés occupied key buildings in the central arrondissements. The next day a red flag flew over the Hôtel de Ville.

On 26 March, elections established a new authority: the Paris Commune. Mandated to affirm the city’s autonomy, its delegates were comprised of Jacobins, devotees to the French Revolution’s most fanatical faction; Blanquists, followers of the veteran socialist, Auguste Blanqui; and members of Karl Marx’s International Workingmen’s Association. Massing outside Paris, Thiers’s forces – the Versaillais – pointed to a foreign conspiracy.

For soldiers like Louis Rossel, however, disgusted at the armistice with Germany, the Commune offered a lifeline. He notified the Minister of War: ‘I do not hesitate to join the side which has not concluded peace, and which does not include in its ranks generals guilty of capitulation.’ In Versailles, mocked since the surrender as defeatists and also blamed for the cannons fiasco, the likes of General Joseph Vinoy spoiled for a reckoning.

While the Commune set about abolishing night work in bakeries and granting pensions to unmarried widows and children, the Versaillais plotted the reconquest of Paris. Troops were saturated with propaganda that depicted a city usurped by the dregs of society, ex-convicts, drunks and foreigners. Soldiers suspected of sympathy were deployed elsewhere in France. Newspapers such as Le Soir informed readers that property recaptured from the Communards would require ‘fumigation’.

In April, following the murder of its military commanders by Versaillais troops, the Commune adopted a Decree on Hostages. For every Communard killed, three hostages would be executed in retaliation. Raoul Rigault, the Commune’s chief of police, began abducting clerics, including the Archbishop of Paris, Georges Darboy. The Communards sought an exchange for Blanqui but Thiers refused, estimating that it would be equivalent to handing over a battalion. Instead, the Versaillais launched missiles on the affluent western arrondissements, pulverising their own side’s houses.

On 16 May the Commune toppled the Vendôme Column, a monument sculpted of melted Austrian and Russian cannons, crowned with a statue of Napoleon Bonaparte in the style of a Roman emperor. Its jingoistic symbolism was an affront to their internationalist values, while its demolition provoked outrage among the Versaillais. General MacMahon conjured its iconoclasm to rouse bloodlust in his troops: ‘Some so-called Frenchmen had the nerve, under the eyes of the Prussians, to destroy this witness to the victories of your fathers over the European coalition.’

On 21 May the Versaillais breached Paris’ defences and swept towards the Arc de Triomphe. The slaughter was already underway as Thiers crowed: ‘The punishment will be exemplary, but it will take place within the law.’ In the western districts, a journalist for Le Gaulois happened upon 30 bodies next to a ditch: they were fédérés strafed by the Versaillais with a mitrailleuse – a rapid-firing weapon similar to a Gatling gun. The Bloody Week had begun.

Barricades at the Place de la Concorde were soon overwhelmed. Bourgeois citizens in the prosperous districts cheered on the carnage as Versaillais troops rained down bullets from upper-storey windows. To impede the enemy’s advance, the Commune ordered that strategic buildings be torched.

Anti-Communards saw this as proof that the Commune was capable only of destruction. Yet there is strong evidence that Versaillais missiles were the primary cause of the inferno that would leave Paris in ruins. Nevertheless, Communards did incinerate landmarks such as the Tuileries Palace, reviled as a symbol of the Second Empire, and the Hôtel de Ville, as they retreated to the eastern arrondissements. From his bedroom in the Marais, the English merchant Edwin Child recorded that by 24 May ‘it seemed literally as if the whole town was on fire’.

Suddenly, rumours of female arsonists – pétroleuses – firebombing buildings became rife. Women caught carrying bottles, even chimneysweeps with blackened hands, were shot on the spot by the Versaillais. Killing was conducted in the open, with as many as 3,000 men and women dispatched in the Jardin du Luxembourg between 24 and 28 May. Children, too, fell victim to the bloodbath. Medical personnel who tended to the wounded or dying were, as the The Times reported, suspected of ‘sympathising with them and thus meriting the same fate’.

Many generals involved in the massacre had earned their stripes crushing indigenous rebellions in French colonies. The Versaillais was a highly disciplined force and the piles of corpses left strewn throughout Paris that week attests to a ruthless mentality that perceived anyone who challenged the ideals of the French state as alien and incorrigible.

Finally, after a rash decision to execute Archbishop Darboy and other hostages, the Commune made its last stand among the tombs of Père-Lachaise Cemetery. On 28 May Vinoy lined 147 fédérés up against its eastern wall and mowed them down. In Montmartre, Eugène Varlin, one of the Commune’s brightest leaders was beaten so savagely that his eyeball was left dangling from its socket before he was killed in the same location as the two generals on 18 March. According to the Journal des débats, the army had at last ‘avenged its incalculable disasters by a victory’.

Around 35-40,000 prisoners were marched on foot to Versailles. Upon reviewing one convoy, General Galliffet had all grey-haired men executed, suspected of having participated in the 1848 Revolution. Bourgeois women lining the route struck prisoners with their umbrellas. Crammed into filthy, open-air prison camps, disease and exposure claimed many lives. In the years that followed, survivors would face firing squads, destitution and banishment to remote penal colonies.

Subsequently, the Third Republic consolidated its grip on France’s national memory. School textbooks highlighted Darboy’s death while trivialising the slaughter of tens of thousands of Parisians and precluded any mention of the military’s eliminationist policy. Within years, a Catholic basilica, the Sacré-Cœur, soared over Montmartre in expiation for the Commune’s ‘sins’. The basilica was financed by the National Assembly, even as it fought against efforts to have ‘Member of the Commune’ inscribed on Communards’ tombstones.

The recent iconoclasm of national idols throughout some parts of the world has prompted fierce debate about the ‘cancelling’ of history, triggering prophylactic jeering among conservative commentators, as it did in 1871. It bears emphasising that the Communards’ plan to tear down contested monuments was no less political than their construction in the first place. According to the Communard Antoine Demay, when Thiers’s mansion was razed in May 1871 the Commune was keen to preserve his many books and artefacts, in order to ‘conserve the intelligence of the past for the edification of the future’, which rather debunks the barbarian caricature pushed by the Versaillais.

In the spring of 2021, two letters addressed to the French government and anonymously written by members of the military warned darkly of national disintegration and civil war because of anti-racist activism and Islamic extremism. In an image that evokes the radical reputation of working-class districts such as Belleville during 1871, the first letter spoke of ‘hordes from the banlieue’ threatening ‘our civilisational values’. The second referenced La Marseillaise, specifically the French national anthem’s seventh verse about avenging the military’s elders. The events of the Paris Commune and the Bloody Week still cast a long shadow over France.

Danny Bird is a writer based in Bristol, UK. A graduate of UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies, he has a special interest in modern European history.