Sex, Violence and Hollywood

Alarm about moral degeneracy and ‘family values’ provoked Hollywood to instigate its own self-censorship codes in the 1920s. The industry's preoccupation with American morality proved to be the source of inspiration and even genius.

Dorothy Mackaill as a secretary-turned-prostitute in the pre-Code Hollywood film Safe in Hell, 1931.

Jane Russell’s breasts were a constant concern to Hollywood’s censors. In 1941 she starred in a movie called The Outlaw. The director, Howard Hughes, wanted to make the most of her generous cleavage, so he designed a cantilevered, underwire bra to give it additional screen time. Russell hated the contraption, found it painful and secretly threw it away but, even without the extra lift, the Production Code Administration (PCA – Hollywood’s censors) still felt there was too much on show. Hughes, however, decided not to fight them. He calculated that a campaign to ban The Outlaw could be just the publicity it needed, so he actively encouraged conservatives to demand that it be denied an audience. The result: The Outlaw was held back in 1941; shown for one week in 1943; and then given a final, eagerly anticipated release in 1946. As Hughes predicted, erotic expectation turned it into a box office hit.

The cleavage controversy did not end there. In 1954 Russell appeared scantily clad in The French Line – a movie that posed an additional problem for the PCA because it was in 3-D. What was merely titillating in 2-D, said the censors, was downright outrageous in 3-D: ‘The costumes for most female characters and especially Jane Russell were intentionally designed to give a bosom peep-show affect beyond extreme décolletage and far beyond anything acceptable under the [studios’] Production Code.’ Flouting the Code’s official list of dos and don’ts, the poster for The French Line carried the tagline: ‘JR in 3-D: Need We Say More?’ An alternative was: ‘It’ll Knock Your Eyes Out!’ The PCA refused The French Line a certificate and the Catholic National Legion of Decency called for a boycott. As you might have guessed, it was one of the most successful films of the year.

On the one hand the Russell scandals confirm the view of the old Hollywood Production Code and its enforcers: puritan, silly, authoritarian. On the other hand, they challenge aspects of the traditional narrative. After all, these movies were not banned or even censored – the industry simply refused to endorse them. And the success they subsequently enjoyed in the cinemas that showed them suggests that the so-called sexual McCarthyism of the 1940s and 1950s was not as all-pervasive as we might think.

It is usually believed that the anti-sex, anti-violence Code was harmful to art, intellectually unsophisticated, imposed from above and un-American in its disregard for First Amendment Rights. This is far from the full picture. Often the Code encouraged greatness, was intellectually nuanced, self-regulated and conformed to American values of Judeo-Christian ethics and free enterprise. For good and bad, it was as American as apple pie.

Pre-Code movies did not go uncensored. They were covered by local laws and edited in deference to public opinion – or at least whatever the movie makers thought they could get away with without triggering an angry backlash. Films produced in the 1920s and early 1930s were made in an era of social change and economic uncertainty. The boom of the Roaring Twenties gave black Americans and poor whites new spending power and provided consumer goods to a generation of women, who wanted to be as socially, even sexually, liberated as men. The sudden, devastating poverty of the Great Depression necessitated a cinema that reflected the struggles of the audience and examined those who resisted the power of greedy bankers. Studios that favoured lavish musicals in the 1920s did poorly in the early 1930s. The more socially realist producers, particularly Warner Bros, survived the worst years of the Depression far better.

You can get a flavour of the pre-Code ethic from a handful of surprisingly bold movies. Local state censors complained that when Little Caesar (1931) depicted Edward G. Robinson going down in a hail of bullets, the kids in the stalls were cheering the gangster rather than the cops. Homosexual characters were on parade in Our Betters (1933), Sailor’s Luck (1933) and Calvacade (1933). In Morocco (1930) Marlene Dietrich played a cabaret singer who dressed as a man in a white tie suit and kissed a girl in the audience. ‘I’m sincere in my preference for men’s clothes’, Dietrich once explained. ‘I do not wear them to be sensational. I think I am much more alluring in these clothes.’

_1930._Josef_von_Sternberg%2C_director._Marlene_Dietrich_with_top_hat-1.jpg)

Audiences paid good money to be allured. The magazine Variety once calculated that out of 440 pictures made from 1932 to 1933, 352 had a ‘sex slant’, 145 had ‘questionable sequences’ and 44 were examples of outright ‘perversion’. Barbara Stanwyck and Joan Blondell showed off their lingerie in Night Nurse (1931). Jean Harlow casually undressed in Red Headed Woman (1932) and flashed a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it bit of breast. In The Gold Diggers of 1933 a typically camp, highly sexualised Busby Berkeley sequence called Pettin’ in the Park featured the female cast getting caught in a downpour, removing their wet clothes in silhouette and finally emerging clad in metal garments, which the menfolk, try as they might, couldn’t get off – until one of them was handed a can opener. Gold Diggers was the third most popular movie of 1933, although it had to be distributed with alternative scenes to circumnavigate the objections of local censorship boards – the kind of tiresome expense that the studios were increasingly growing sick of.

The desire for a unified, industry-wide censorship programme came from within the industry itself. Hollywood faced a constant battle against local censors and a constant fear that the federal government might get involved. In order to pre-empt state regulation, private enterprise decided to come up with its own set of artistic regulations. In 1922 the studios created the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors Association (later known as the Motion Picture Association of America). They gave Will H. Hays, a Republican lawyer and Presbyterian deacon, a salary of $100,000 and an unlimited expense account to launch a campaign against censorship that, perversely, would end with Hollywood censoring itself.

The first official list of ‘dos and don’ts’, drawn up in 1927, was largely ignored. It was only with the popularisation of sound and a growing ‘family values’ backlash among churchgoers that the campaign for active self-censorship within Hollywood gathered momentum. In 1929-30 Father Daniel Lord, a Jesuit priest and instructor at the Catholic St Louis University, wrote what was variously known as the Hays Code or the Production Code. This stipulated what must not be shown but also defined what should be seen instead. It clamped down on depictions of ‘pointed profanity’, ‘any inference of sex perversion’, ‘suggestive nudity’, ‘childbirth’, ‘brutality’, ‘sedition’ and ‘ridicule of the clergy’ – and it urged promotion of wholesome, American values that would improve the morals of the audience. A clause was inserted against miscegenation, in deference to the ugly racial attitudes of the time. This was protested strongly by the clerics involved in the original draft but it stayed put. After all, the economic goal of the Code was to expand audiences by pre-empting local censors and scenes of affection between blacks and whites were a no-no down South.

In 1934 the Production Code Administration (PCA) was created, which required all films released on or after 1 July 1934 to obtain a certificate of approval based upon their content. The head of the PCA, taking over from Hays, was the Catholic Joseph Breen, a man with decidedly mixed attitudes towards Hollywood. A religious chauvinist and rabid antisemite, he once wrote of the studio management, ‘These Jews seem to think of nothing but money making and sexual indulgence’ – an uncomfortable reminder that in the Code era Hollywood was dubbed ‘A Jewish-owned business selling Roman Catholic theology to Protestant America’. Yet what he was not was an inquisition priest seeking to hurl great, yet morally ambiguous, art onto the fire. On the contrary, Breen loved movies and saw his role as a script editor ensuring high quality. The producer Val Lewton once explained:

Mr Breen goes to the bathroom every morning. He does not deny that he does or that there is no such place as the bathroom, but he feels that neither his actions nor the bathroom are fit subjects for screen entertainment. This is the essence of the Hays Office attitude … at least as Joe told it to me in somewhat cruder language.

No one can deny that the Code ushered into Hollywood an era of moral conservatism that reversed the liberal, even liberating, trends that preceded it, especially for women. But an exploration of the Code’s philosophy and how it worked out in practice punctures a number of myths. For a start, it is important to remember that this was not a state-mandated infringement of First Amendment rights of freedom of speech. The Supreme Court had already asserted that movies were in fact commerce rather than art, so the First Amendment often was deemed not to apply anyway. More importantly, the Code was something that the studios adhered to voluntarily in order to make federal censorship unnecessary. Its supporters believed that it accorded entirely with classical liberal, free market principles.

Also, strictly speaking it is inaccurate to call the Code ‘reactionary’. Nowadays, we tend to think of anything that tells us what to do with our private lives as offensively authoritarian. Back then, the progressive utopian spirit said that strong morals promoted liberty by creating individuals free from the antisocial addictions of sex and violence. The Code bore comparison with federal legislation to regulate the quality of food and drugs, with programmes designed to help the poor, or even with Prohibition, the great, failed experiment in creating a sober citizenry. In the words of the cultural historian, Thomas Doherty, the Code:

evinced concern for the proper nurturing of the young and the protection of women, demanded due respect for indigenous ethnics and foreign peoples, and sought to uplift the lower orders and convert the criminal mentality. If the intention was social control, the allegiance was on the side of the angels.

The Code rejected the idea that art is amoral, for, it stated:

This is true of the THING which is music, painting, poetry, etc. But the THING is the PRODUCT of some person’s mind, and the intention of that mind was either good or bad morally when it produced the thing. Besides, the thing has its EFFECT upon those who come into contact with it. In both these ways, that is, as a product of a mind and as the cause of definite effects, it has a deep moral significance and unmistakable moral quality.

The Jesuitical tone of the Code reflected a mature and nuanced idea of what was wrong and right, but also a deep conviction that the public, too, was on the side of the angels. Theatre goers broadly concurred that homosexuality was perverse, drugs evil, whisky a gateway to sin. Not that the Code was heartless towards sinners or wanted to discourage films that showed the realities of life:

Sympathy with a person who sins is not the same as sympathy with the sin or crime of which he is guilty. We may feel sorry for the plight of the murderer or even understand the circumstances which led him to his crime: we may not feel sympathy with the wrong which he has done.

Hence, sin could be shown but only if it was shown to have bad consequences.

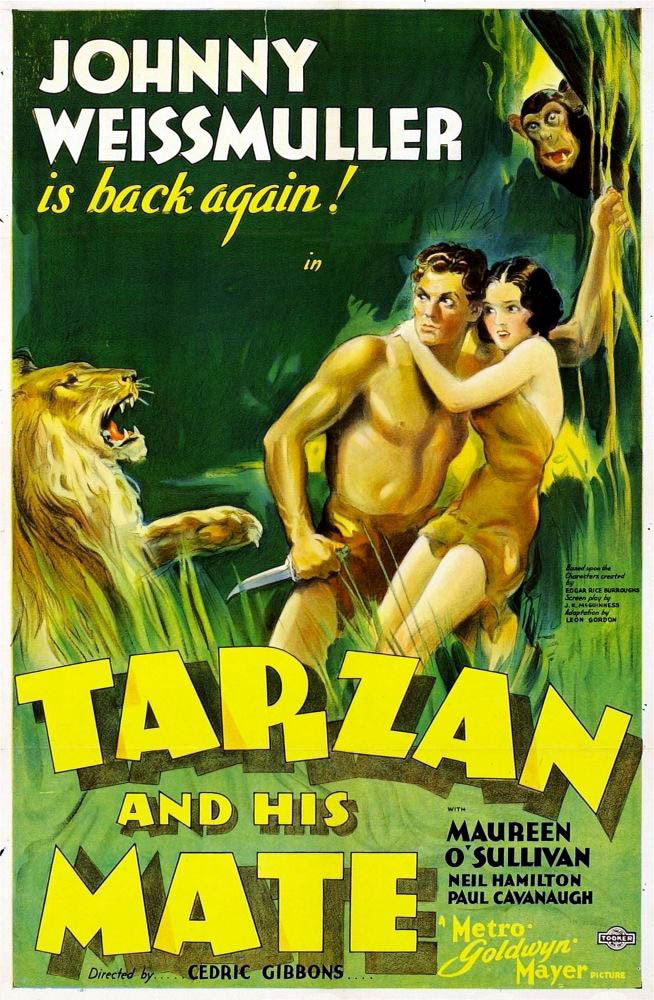

What were the artistic consequences for cinema? It is alleged that the Code a) squeezed sex out of movies and that b) women’s sexual identity was reduced to that of virginal housewife. For example, the first movie to fall foul of the Code was Tarzan and His Mate (1934). The Tarzan films had hitherto been emblematic of the pre-Code spirit: sexual, violent and featuring male and female heroes who enjoyed almost equal status. (Time magazine noted that the leads obeyed ‘No civilized conventions except, perhaps, those of birth control’.)

Tarzan and His Mate featured a sequence in which a body double for Jane swam in the nude. The PCA refused to approve the movie; MGM protested. MGM lost and cuts had to be made, proving, for the first time, that the Code had real teeth. Thereafter, the Tarzan cycle became emblematic of Code conservatism. Jane became a housewife, the couple had a son (out went the birth control) and by the time RKO took over the franchise in 1943, Tarzan was just a comic-book character fighting man-eating plants in his loincloth.

For many feminist writers the Code also turned women into victims, creating movies that the critic Molly Haskell called ‘soft-core emotional porn for the frustrated housewife’. Dark Victory (1939) starred Bette Davis as ‘everything a woman could dare to be!’; she drank, she smoked, she seemed to spend her entire life saying witty things in bars. When Davis’ character discovered she had a brain tumour and was doomed to die, she decided that she had to give up the fast living and settle down with the doctor who so patiently loved her. Davis’ character was compelled by fate to reconcile herself to what she should, according to the Code, have always been: a satisfied wife. The Code could be so depressingly repressive that it even insisted that the cartoon flapper Betty Boop covered up her shoulders and straightened out her curls.

Yet the idea that sex and violence were thematically crushed by the Code is fanciful; it simply shifted them from something stated to something implied, often in a highly creative manner. In his book Ulysses Unbound: Studies in Rationality, Precommitment, and Constraints the political and social theorist Jon Elster gives examples of the Code actually increasing the sexual or dramatic tension of a scene. For instance, the script of Key Largo (1948) initially called for Edward G. Robinson to taunt Lauren Bacall with sexual suggestions; Bacall then spat in his face. Recognising that Breen would never tolerate the scene, the words were whispered inaudibly instead. This invited the audience to imagine their content, adding a fresh charge to the moment, turning the audience from passive spectators to active participants in the spectacle.

Elster quotes the director George Cukor recalling that: ‘The great rule was that if there was a kiss, the parties had to keep one foot on the floor. But in spite of those restrictions, I have a feeling that it was a lot more erotic, that there was an atmosphere of eroticism.’ Two examples confirm the theory. When Hitchcock made Notorious (1946), the rule was that no kiss could last more than three seconds. So Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman kissed for two seconds, broke away, kissed, broke away, kissed again and so on for what felt like an eternity of sexual tension. An equally astonishing ‘tease’ was accomplished in The Seven Year Itch (1955), in which Marilyn Monroe stood above a grate and her white dress ballooned upwards. That scene, argued the film theorist Andre Bazin:

could only be born in the world of a cinema with a long, rich, Byzantine tradition of censorship. Inventiveness such as this presupposes an extraordinary refinement of the imagination, acquired in the struggle against the rigorous stupidity of a puritan code. Hollywood, in spite and because of the taboos that dominate it, remains the world capital of cinematic eroticism.

Indeed, one might argue that Monroe’s sex appeal was always as much about the amount of her flesh that was not shown as the amount that was. Her smile, bosom and wayward skirt hinted at endless sensual possibilities just out of reach. This is the difference between the erotic and the pornographic.

Nor did the Code entirely reduce women to passivity. When we first meet Jane Greer in 1947’s Out of the Past, she is a victim: a prim, pretty gangster’s moll who has fled her violent lover. Robert Mitchum beds her and would love to wed her, but halfway through the movie, everything changes. Greer kills a hoodlum, disappears and sets up Mitchum as a patsy for a crime. It turns out that the lady is a vamp: she’s the one who’s been pulling the strings all along. Yes, she’s evil and, yes, she’s given the Code-approved, just-desserts ending. But women viewers could watch Greer or Bette Davis in All About Eve (1950) or Mary Astor in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and see women who used their sexuality to dominate supposedly superior men.

Gay and lesbian characters found a way into Code-era movies, too. Mrs Danvers in Rebecca (1940) was the Hollywood archetype of the lesbian: commanding and hauntingly obsessed with her previous employer. Plato in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) was her gay mirror opposite: feminine and obsessed with the far more masculine James Dean character. True, both Danvers and Plato were crude stereotypes that depicted homosexuals as victims. But the existence of those stereotypes, and the filmmakers’ assumption that an audience would understand them, indicated that for all the ‘moral consensus’ that the Codes’ authors presumed, gay and lesbian people were still around in the 1940s and 1950s and were still to some degree visible. Many of them would watch such movies and read into them meanings that their makers never intended. Hence Written on the Wind (1956), Spartacus (1960) and All About Eve have been reclaimed as ‘camp classics’: films either so melodramatic or sexually ambiguous that gay and lesbian viewers regard them as sympathetic.

This emphasises a key argument in film theory: a movie can be written to mean one thing but be interpreted by different audiences to mean quite another. The viewer is not just a passive spectator but a participant in the creative process. In other words, the Code had no power to stop gays, women, poor people or ethnic minorities from drawing subversive interpretations from movies constructed to reflect a conservative view of the world. There was a moment of schadenfreude for those who despised the moralism of the Code when some of the works that it approved of matured into gay classics. In Clueless (1995), the dizzy heroine invites an attractive James Dean lookalike to a sleepover in the hope of seducing him. She is confused when he refuses to put out. But the audience knows exactly what’s going on the moment he suggests that they watch Spartacus.

Proof of Hollywood’s sensitivity to market forces is the fact that its holy Code was fairly easily undone by changing tastes. The Code reigned supreme so long as the studios deferred to it out fear of a boycott or cinemas refused to show uncertificated movies. But when both realised that the public’s appetite for sex and violence was growing and becoming more profitable, they began to disregard the moralists. Some Like It Hot (1959) and Psycho (1960) were both released without a certificate and still made enormous profits.

There then followed a series of test cases in which the Motion Picture Association of America was confronted with movies that clearly flouted the Code but whose producers were determined to get them on the market anyway: The Pawnbroker (1964) for sex and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) for language. Rather than reject works of obvious quality and mass appeal, the MPAA broke its own rules and let them pass.

The Code was effectively abandoned in the mid-1960s, heralding a new era in which audiences were limited by age to certain films but the idea of trying to dictate content was dropped. The end of the Code era shows that Hollywood was only partly motivated by moral concerns. Its primary ambition was to make money and it only self-censored so long as smut and violence threatened its ability to do so. When the market turned liberal, Hollywood followed. In the field of morality, Hollywood rarely drives social change in the way that conservatives accuse it of: it slavishly follows popular taste.

Moreover, censorship did not inhibit artistic achievement. There were two golden ages of Hollywood and both negotiated with the Code in a manner that proved conducive to great art. The 1930s and 1940s were the period in which the Code was enforced and its strictures compelled moviemakers to be a little more imaginative and elegant than they might otherwise have been. They learned that ‘less is more’ and created restrained, lyrical, often highly erotic films that were incredibly poetic.

By contrast, the 1970s was a period in which directors challenged the conventions of the dying Code in both content and theme. Films such as Klute (1971) featured sex and prostitution. The Wild Bunch (1969) contained a cast of bloodthirsty anti-heroes. The criminals in The Godfather (1972), Dog Day Afternoon (1975) and Badlands (1973) were sympathetic rather than simply monstrous. Yes, the 1970s tore up the Code, but by being so self-consciously iconoclastic it acknowledged the legacy of the morality that had come before and the importance of the archetypes and standards that it created.

Whether the movie industry was promoting certain ethics or challenging them, negotiation with popular American morality proved to be the source of inspiration and even genius.