Soft Fascism

The buildings that came out of Portugal’s New State were described as an ‘architectural lie’.

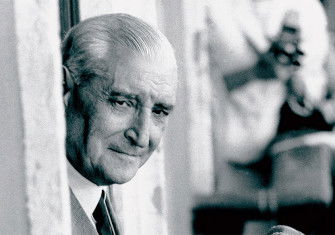

The Portuguese Estado Novo (New State) is not remembered as a particularly aggressive dictatorship. This is largely due to propaganda. Founded by António de Oliveira Salazar in 1933, the regime remained in power for 41 years, enough to outlive every other far-right regime in Europe. Throughout that period it consistently marketed itself as a different form of authoritarianism – an accessible, even affable, one.

The Portuguese Estado Novo (New State) is not remembered as a particularly aggressive dictatorship. This is largely due to propaganda. Founded by António de Oliveira Salazar in 1933, the regime remained in power for 41 years, enough to outlive every other far-right regime in Europe. Throughout that period it consistently marketed itself as a different form of authoritarianism – an accessible, even affable, one.

To its European citizens, the state positioned itself as a strict, but paternal, figure; to the colonised peoples in Africa and Asia, it posed as a ‘good coloniser’, a purveyor of advanced civilisation and evangelisation. Outwardly, the New State professed to want nothing more than to elevate ‘God, country and family’. Reality, however, was rife with human rights abuses common to other fascist regimes: censorship, closed borders, political policing and violent repression of independence movements in forcefully occupied territories.

This duality persisted throughout the entire lifespan of the New State and would go on to play a part in its architecture.

Portugal had long struggled to find a sense of national identity in its architectural exploits. The Manueline and Pombaline styles had left their mark in the 16th and 18th centuries, equipping the Portuguese capital with buildings such as the Jerónimos monastery or the Praça do Comércio, but the 20th century had so far failed to produce a worthy successor.

The New State attempted to fill this architectural void in the 1940s by introducing a new brand of ‘authentic’ Portuguese architecture in a series of large-scale public works.

Featured everywhere from courthouses to small-town post offices, this nostalgic style employed state-of-the-art engineering and construction techniques, but aimed to conceal them under decorative elements that exalted a simpler, more rural existence. Unlike German and Italian exercises in neoclassical and modernist grandeur, this was a decidedly provincial style: many buildings featured raw masonry walls, ceramic tile roofs, wrought-iron balconies and a variety of towers and pyramidal spires, often topped by a weather vane or an armillary sphere. The latter had been a widely recognised national symbol since King Manuel I had employed it as a personal heraldic badge in the 1500s. Its use as a decorative element created a continuity with this distant past, legitimising the New State. At the same time, the sphere had strong imperialistic connotations, acting as a visual reminder of Portugal as a global nation – composed of the European mainland, the archipelagos of Madeira and Azores and the ‘overseas provinces’ of Angola, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe, Cape Verde, Macau, Timor and Portuguese India (Goa, Daman and Diu).

There are perhaps no better examples of this form of New State architecture than the elementary schools of the 1940s and 1950s. In that period, the state built over 7,000 new schools in villages and towns all over the country: stout, usually single-story buildings fronted by an imposing double door, offset to the left or right, and a row of large, multi-panelled windows. On the inside, each building featured two to four classrooms, a kitchen, toilets and a back porch. No two schools were exactly the same, however, as the quest for authenticity meant that each one should fit its surroundings, rather than stand out as a mid-century addition to the landscape. For this reason, northern schools were built out of granite, while southern schools were covered in traditional white lime paint, offset by a thick strip of ochre or blue on the lower half of the wall. Most of the schools survive to this day and many retain their original purpose, but the New State’s plan to endow each village and town with an elementary school did not pay off. By the fall of the regime in 1974, Portugal still suffered the lowest compulsory education and highest illiteracy rates in Europe.

The New State’s favoured form of architecture was similarly unsuccessful. Unassuming as it may have looked, this was a style that attracted many detractors, who found it not only unimaginative, devoid of any creativity or ambition beyond that of reinforcing past glories and achievements, but also downright hypocritical. In the words of the architect Fernando Távora, a critic from the period: ‘There exists, in Portuguese homes, an architectural lie that does not correspond to the Portuguese truth and that, therefore, should be entirely banished.’

This ‘architectural lie’ underlies the name the style would acquire from its detractors: Português Suave (‘Soft Portuguese’), a thinly veiled insult that not only compared the style to a cheap brand of national cigarettes with which it shared its name, but reached deep into the contradictions of the regime. It was a popular notion then, as it is now, that Portugal was a country of ‘gentle customs’, unwilling to stoop to the brutality of neighbouring fascist regimes. It made a morbid kind of sense, then, that such a country would take to a similar embellishment of its architecture, using patriotic symbols and traditional materials to camouflage modern engineering and construction techniques.

The outcry against Soft Portuguese style gained traction in the first ever Congress of National Architecture in 1948, where proponents of Modernism gathered to discuss the present and future of national architecture. According to them, Soft Portuguese created nothing and achieved nothing, being as it was a mere rehash of tried-and-tested elements, which pleased the undiscerning masses but did little to impress the experts. This sentiment would be the proverbial nail in the coffin of Soft Portuguese, which would not survive into the following decades.

As for the New State, it fell on 25 April 1974, in a largely bloodless coup d’état known as the Carnation Revolution. The political pendulum swung heavily to the left and the ideological remnants of the regime were swiftly erased from collective memory. The physical remnants, however, were left relatively untouched. This allowed Soft Portuguese to remain an integral part of the landscape to this day: in the form of elementary schools, post offices and courthouses, now staffed by the citizens of a democratic country.

Rafaela Ferraz writes about Portuguese history.