The Spanish Witches of Cartagena

The Spanish Inquisition arrived in the New World convinced of the existence of heretics and witches. Learning to navigate the Inquisitors’ demonic expectations was one way to survive, as shown by the case of Paula de Eguiluz.

The Inquisition Tribunal by Francisco de Goya, c.1808-12.

On 25 March 1638, nine individuals were brought into the Main Square of the colonial city of Cartagena in front of a large crowd. There, in what is now the Plaza de Bolívar, they underwent a public trial conducted by the Spanish Inquisition, which had established an office in Cartagena in 1610. Its first Grand Inquisitors, Don Mateo de Salcedo and Don Juan de Mayozca, were introduced to the city with a Mass in the cathedral, where they announced both their powers and their intention of persecuting Jews, Muslims, Protestants and witchcraft. Soon, Cartagena would occupy a central place in the Inquisition’s battle to maintain Catholic orthodoxy by persecuting its many perceived demons in the New World.

That day eight Portuguese men were found guilty of practicing Judaism, but the ninth conviction was different and produced something of an uproar among the crowd. It found Paula de Eguiluz, a formerly enslaved woman, guilty of witchcraft, for the second, but not the final, time in her life. According to the official record of the public hearing, when her conviction was announced ‘it was not possible to read the sentence out loud because of the murmuring of the people’.

Paula de Eguiluz was born into slavery in Santo Domingo in 1592. In her twenties, she was purchased by Joan de Egauiluz, a Cuban slave-owner and miner, and moved to Havana. There, she would give birth to three of his children and take his last name before, in 1623, she was arrested, accused of witchcraft, murdering a newborn child and drinking his blood. She was taken to Cartagena to face the Inquisition.

Paula de Egauiluz denied the accusations and claimed that their basis was the jealousy of her neighbours who envied her because Joan de Egauiluz ‘loved her and kept her well-dressed’. One of Paula’s Cuban neighbours, who worked as a sacristan, testified against her claiming that ‘despite being well dressed, she was never seen at church’. According to court records, Paula explained that she had not drunk the baby’s blood, but had ‘put rosemary and lavender as treatment for his swollen belly, at the request of the mother’.

After a three-month trial, which possibly included torture, Paula confessed to being a servant of the devil, recruiting other witches and killing the baby. In her confession, the records explain that she claimed that the ‘devil took her memory away ... and that she confessed because she believed in our Lord Jesus Christ and wanted to preserve her eternal soul’. Condemned as a witch, she was sentenced to 200 lashes, permanent exile from Cuba and was made to work for two years in a public hospital wearing a sanbenito, a penitential hat decorated with flames worn by heretics at the Inquisition’s behest.

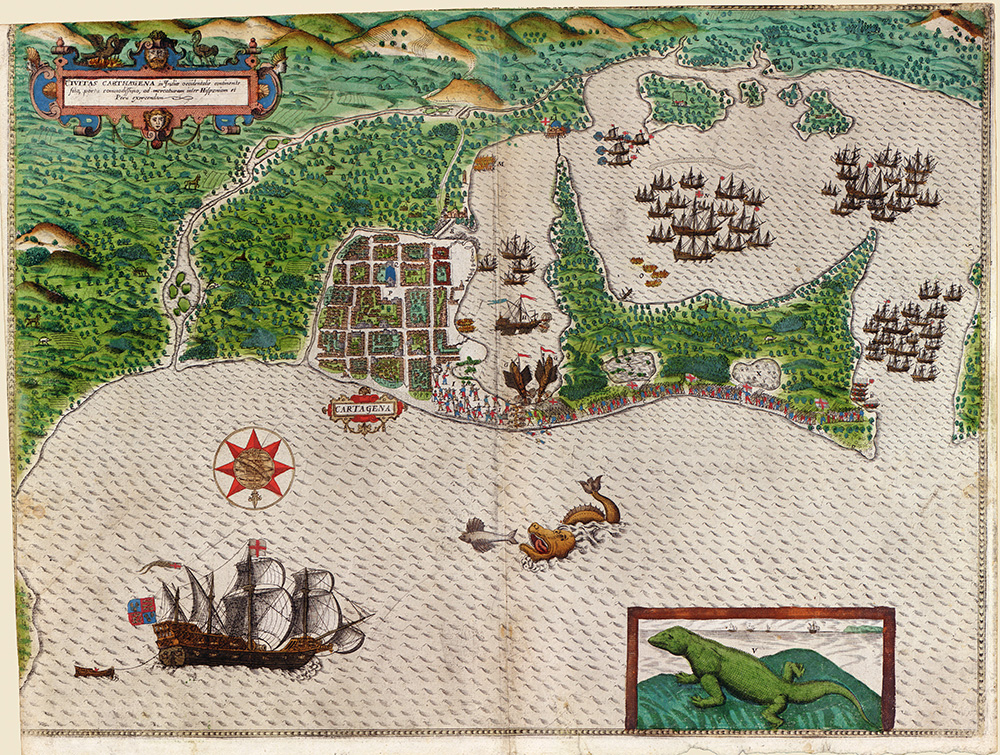

Of the 538 cases of witchcraft judged by the Spanish Inquisition in the Americas, more than half took place in Cartagena. Founded by the Spanish commander Pedro de Heredia in 1533, Cartagena de Indias was named after a Spanish city in Murcia and was built over an indigenous settlement called Calamari. It soon became one of the most important Spanish ports in the New World, the last point of departure for silver and gold being shipped to Europe. This made it an attractive destination for pirates and privateers. The city was attacked and plundered several times, most notably by Francis Drake, who destroyed the city’s cathedral in 1586. In response, the Spanish built a fortress and a wall around Cartagena, giving it its nickname ‘la ciudad amurallada’, the walled city.

Almost all of those condemned of witchcraft in the city were women, but the sentences tended to be less severe than in North America or Europe. The most common punishment was public shaming and enforced labour at public hospitals. This was partly for pragmatic reasons: the Spanish needed cheap labour to support the different economic enterprises of their new empire, such as mining and agriculture. The Spanish monarchy did show some ostensible concern for the indigenous populations of the New World. In 1503 Isabella I of Castile signed a royal provision against indigenous forced labour: ‘each one should work as a free person and not as servants, and they must be treated well; and better the Christians than the others. And do not allow anyone to mistreat them’.

Alarmed at the demographic collapse of the indigenous population that followed the Spanish arrival, in 1542 Isabella’s grandson Charles V signed the New Laws of The Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians, stating that there was ‘no cause or motive to create slaves’. Pedro de Heredia himself faced a trial in Cartagena in 1548, and again in 1552, in which he was accused, among other things, of abusing the local population. Found guilty, he returned to Spain to appeal his sentence, but his ship sank during the voyage in 1554, and he was presumed dead.

Charles’ son, Philip II, went even further in a royal decree of 1593, telling his officials that ‘Spaniards that insult, mistreat, and offend must be punished with greater rigour, as if those crimes were committed against other Spaniards’. Such provisions, however, did not extend to those trafficked in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. In 1571 Phillip granted Cartagena status as an authorised slave port and market. In the 50 years that followed, it became the site of the biggest slave market in Spanish America. More than 300,000 slaves were sold in that period; by contrast, the city had fewer than 13,000 inhabitants.

Two years after her first trial in 1623, Paula de Eguiluz became a free woman and moved to Getsemaní, a neighbourhood developed by free black men and women. Once considered a poor and dangerous place, today it is a tourist destination. While there is no written record of how or why Paula became a free woman, it is probable that Joan de Egauiluz freed her in Cartagena, so as to avoid association with a woman who had been convicted of witchcraft. She worked as a laundress and as a curandera, or ‘healer’. Her clients were predominantly free black and mixed race women, though she also had wealthier patrons. She offered them potions, rituals and prayers to guarantee their husbands’ fidelity and also enhance their own sexual performance. She was often paid up to 50 pesos for her work, at a time when a bottle of wine – a luxury item imported from Spain – cost five pesos.

In 1632 Paula was accused of relapsing into witchcraft. During her defence she oscillated between blaming the Inquisitors for failing to protect her from the devil, criticising the local elites, supplying names of other supposed witches and calling on many of her customers and friends to testify in her favour. Then, in 1634, before a decision had been made, a third trial started. Several of those women named by Paula as witches during her second trial had accused her of being their leader. In 1638 she was found guilty of being a witch for a second time.

Although it is unclear what punishment she received following her second conviction, in 1649 the Spanish friar Pedro Medina, an Inquisitor charged with sending reports to Spain, wrote that Paula had reconciled with the church, was a regular visitor to the prisons, provided alms to other women accused of witchcraft and was a valued member of the community. Her associations with witchcraft did not deter Pérez de Lizarraga, the Bishop of Cartagena, from requesting her healing services before his death in 1647.

It is likely that over the course of her trials, Paula came to understand the sort of story her interrogators wanted from her, one that gave credence to their belief and fears of indigenous witchcraft. In his study Recreating Africa, the historian James H. Sweet quotes the Portuguese priest André João Antovil, who warned slave owners that those who used excessive punishments risked encouraging their slaves to ‘take revenge upon them, using either witchcraft or poison’. Yet while fearing witchcraft, its supposed existence also provided the colonial authorities with an excuse to control the knowledge, bodies and behaviour of indigenous and enslaved women. Many suffered horrible treatment; the Inquisitors believed that humans were most truthful under torture. In 1649, in a letter to the Supreme Council of Inquisitors, Friar Pedro Medina reported that Paula had used her abilities to care for the four Inquisitors that had condemned her ten years previously.

In 1635, Rufina and Diego Lopez, a mixed race couple, were accused of witchcraft and confessed under torture. Court records show that Rufina tried to change her statement, telling the Inquisitors that Paula de Eguiluz had advised her to maintain her original confession. For the Inquisitors, this was proof of the existence of a group of witches in Cartagena. But for Paula and other such condemned women, learning what the Inquisitors wanted to hear, and providing them with these stories of supernatural power while showing remorse and pleading forgiveness became a strategy for survival in an overwhelmingly unjust society.

Santiago Flórez is an anthropologist, educator, writer and illustrator based in Bogotá, Colombia.