Unicorns

A mythological creature of extraordinary resilience.

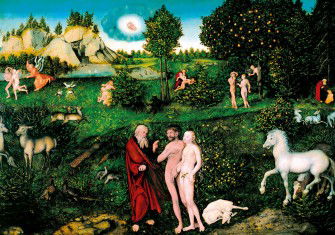

A unicorn falls asleep on the lap of the Virgin Mary in Domenichino’s The Virgin and the Unicorn, painted in 1605, which hangs in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. In Christian thought, the unicorn represents the incarnation of Christ, a symbol of purity and grace that could be captured only by a virgin.

Yet the myth of the unicorn long predates Christianity, having roots, possibly, in the Bronze Age Indus Valley Civilisation of what is now Pakistan, where it is depicted on seals (though some scholars have argued that these may just be a bull in profile).

The Greeks considered unicorns part of the natural world rather than of myth. Ctesias, in his work Indika (‘On India’), described an animal, possibly from Iran, looking like a wild ass with a horn. Pliny the Elder described a ‘monoceros’, combined of elements of a stag, elephant, boar and horse. Chinggis Khan is reputed to have met a unicorn bearing a prophecy.

In medieval Europe, the unicorn, in the form of a horse-like creature, became a staple of chivalric authors, such as Thibaut of Champagne. A lover and his lady are compared with the unicorn and the Virgin. During the Renaissance, as humanism spread, it became a secular symbol of chastity and fidelity.

The unicorn is strongly associated with Scotland. Since the Union in 1707, the royal arms have been borne by a lion, symbolising England, and a unicorn. More recently, ‘unicorn’ has been adopted as a term for privately owned start-up companies worth more than US$1 billion; a symbol of rarity. Unicorns have become ubiquitous in what has become known as ‘princess’ culture, targeted at young girls, while their association with rainbows has seen the unicorn embraced by LGBT activists. A versatile creature indeed.