We All Scream for Ice Cream

Sweets made of ice or snow have been with us for millennia, evolving slowly into the modern chilly treat.

Who doesn’t like ice cream? According to the International Dairy Foods Association, 3.7 million tons of it are consumed in the US each year alone – an average of 23lbs per person. But, while we are only too eager to guzzle it down, we seldom pause to consider how our favourite frozen dessert came into being.

‘Ices’ – that is to say, desserts made of ice or snow – have been around for millennia. As far back as the fifth century BC, the ancient Greeks were refreshing themselves with snow flavoured with honey or fruits. Although Hippocrates famously disparaged snow-water as unhealthy and warned his patients to steer clear of chilled drinks (which he thought produced ‘fluxes of the stomach’), these icy treats enjoyed tremendous popularity throughout the Aegean – so much so that, one hundred years later, no less a figure than Alexander the Great could be counted among their admirers. The Persians were equally enthusiastic. At about the same time as Hippocrates was criticising his fellow Greeks for eating ices, they developed faloodeh, a dessert made from rosewater-flavoured snow and vermicelli-like noodles. The Romans got in on the act, too. While Seneca and Pliny the Elder criticised Nero for having ice carted down from the mountains simply to cool his swimming pool, for example, they seem to have seen nothing unusual in his fondness for chilled wines and snow flavoured with honey.

Technological changes

The popularity of ices necessitated an important technological shift. Unless you wanted to eat your ices in the depths of winter, or high up in the mountains, you needed not only to bring snow or ice to where you wanted to consume it, but also to find some way of storing it in warm weather. This required a special sort of building, now known as an ice house. Often built underground and generally insulated with straw, these stone chambers were sufficiently cold to preserve ice that had been cut from frozen lakes and rivers in the winter, or snow that had been brought down from the mountains. When exactly they came into being is a matter of some debate. It has been suggested that the Babylonians may have built rudimentary ice pits as early as the second millennium BC and there is some evidence to indicate that, much later, Alexander the Great had an ice house, too. But that they were in regular use in ancient Rome is beyond doubt; and their growing prevalence soon facilitated the development of a thriving snow trade, criss-crossing Europe, the Near East and the Mediterranean. By the later Middle Ages, snow was on sale in most large ports.

Matter of physics

Yet ice cream – made with frozen dairy products, rather than snow or ice – did not come until much later. It wasn’t for want of trying. During the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), for instance, the Chinese made a cold, creamy gloop by packing buffalo milk, flour and camphor in snow. But while it was easy enough to cool milk down, it proved remarkably difficult to freeze it. It was all a matter of physics. As we now know, most cows’ milk freezes at somewhere between -0.535°C and -0.565°C, a little below the freezing point of water; and packing it in snow doesn’t get it cold enough to become a solid.

The challenge was, therefore, to work out not just how to store snow and ice, but how to make it colder once you’d got it, as well. Surprisingly, the solution to this seemingly intractable problem was salt. When salt is added to snow or ice, energy is absorbed from the surrounding environment – thus producing a rudimentary form of refrigeration.

As early as the mid-16th century, foodies were beginning to cotton on to the potential of this process. In Magia naturalis (1558), for example, the Neapolitan polymath Giambattista della Porta described how ice laced with salt could be used to freeze wine – which, like milk, has a freezing point below that of water.

When a mixture of salt and snow or ice was first used to produce ice cream, however, is something of a mystery. There are plenty of legends. Some say that Catherine de’ Medici brought the recipe with her to France when she married Henri, duc d’Orleans in 1533, while others suggest that Charles I of England gave his chef a lifetime pension to keep the original recipe a state secret. These are, however, nothing more than 19th-century fantasies – every bit as nonsensical as the claim that Marco Polo brought ice cream back from China in the Middle Ages.

Although it is hard to be certain, the earliest form of ice cream seems to have been produced a little before Della Porta started freezing wine. As the historians Caroline and Robin Weir have recently pointed out, the first printed references appear in Europe around 1530. Yet it was not until the publication of Mrs Mary Eales Receipts in 1718 that the first recipe appeared in English. Even then, the process described was laughably vague. ‘Take Tin Ice-Ports’, Eales explained, ‘fill them with any Sort of Cream you like, either plain or sweeten’d, or Fruit in it; shut your Pots very close … set it in a Cellar where no Sun or Light comes, [and] it will be froze in four Hours, but it may stand longer …’

Refined process

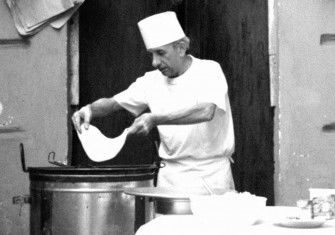

By 1768, when M. Emry published the very first ice-cream recipe book – L’Art de bien faire les glaces d’office; ou Les vrais principes pour congeler tous les Rafraichissemens – the process had become more refined. Greater care was taken to describe exactly how long milk would take to freeze; how the ice and salt should be packed; and how the ingredients could be protected from contamination by the refrigerants.

Still, there was considerable scope for variation. Milk, cream and custard were used almost interchangeably; and the flavourings could be even more diverse. As Jeri Quinzo has shown, the authors of recipe books recommended using rose petals, crushed macaroons, caramel, ginger, lemon, musk, chocolate, laurel, tarragon, parsley and even asparagus.

Thomas Jefferson’s Vanilla Ice Cream

For many years, historians assumed that these early ice creams were consumed primarily by elites – and it is not hard to see why. Most recipe books were written by those who catered to aristocratic, or even royal households; and there is abundant evidence of ice creams being served in an unambiguously ‘elite’ context. During the 18th century, for example, the Sèvres Manufactory produced a range of beautiful ice-cream coolers and dishes for Louis XV and his court; in 1813, President James Madison’s wife arranged for ice creams to be served at his inauguration ball in Washington DC; and, 25 years later, Balzac delighted in describing the lavish plombiers, which were served as a dessert in the great houses of Paris in his novel, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes (1838-47).

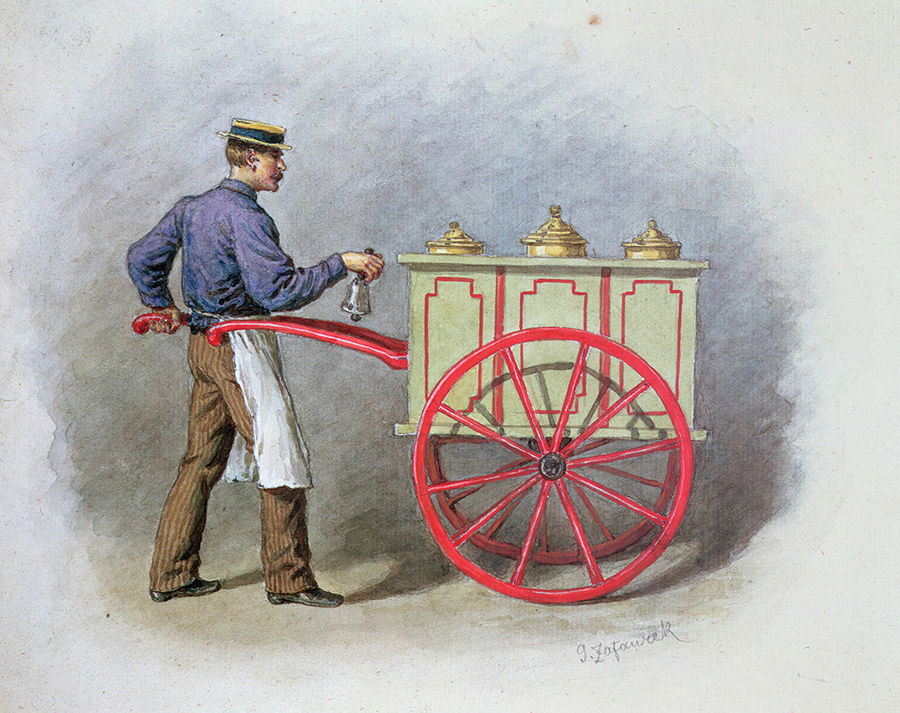

But as Melissa Calaresu has argued, ice cream was not just the preserve of the elites – especially in 18th-century Naples. Partly because of the vibrancy of the snow trade, it was possible for people much lower down the social scale to make, sell and enjoy ice cream as well. Not only were there plenty of shops and cafes selling ice creams, but there was also a host of vendors who sold it in the streets; and there is evidence to suggest that many families may have made it at home, as well.

Silky smooth

Irrespective of who was eating it, however, early ice creams were still some way from being the chilly treat we enjoy today. Since the milk, cream or custard was static when it was frozen, it tended to form large, icy chunks, resulting in a grainy – even lumpy – texture. In 1843, however, Nancy Johnson, a resident of New Jersey, invented a hand-cranked freezer, which allowed her to make silky-smooth ice cream. This consisted of a large tub, containing layers of ice and salt, a tightly closed cylinder for the ingredients and a removable handle, which could be turned to agitate the ice cream until it was properly frozen.

Even with Nancy Johnson’s freezer, however, it was only possible to make a relatively small batch of ice cream at a time, meaning that supply could never keep up with demand. Only when Clarence Vogt of Louisville, Kentucky invented the continuous freezer in 1926 did it become possible to produce ice cream on an industrial scale. The resulting explosion in output pushed prices down, making smooth, creamy ice cream available to everyone, everywhere; and, as more companies started manufacturing their own brands, increased competition led to the standardisation of core ingredients and to ever more inventive flavours.

By the middle of the 20th century, ice cream had become big business. In response to ever-growing demand, new techniques of pasteurisation, homogenisation and freezing were developed and specialist enterprises began to dominate the market. Despite their humble beginnings, Baskin-Robbins (est. 1945), Häagen-Dazs (1961) and Ben & Jerry’s (1978) have all become multinational firms, boasting a wide range of distinctive flavours and instant brand recognition the world over.

Because of its easy availability and endless variety, ice cream has become synonymous with leisure and comfort. But if you take a moment to remember the technological leaps that were needed to make ice cream what it is today, it’s sure to taste even better.

Alexander Lee is the author of Humanism and Empire: The Imperial Ideal in Fourteenth-Century Italy (OUP, 2018).