When Did the Medieval Period End?

As conventional wisdom has it, Europe began to see the light at the end of a dark age sometime around 1500. Four experts try to date the birth of modernity.

‘Humanist scholars certainly thought themselves to be living in a new age’

Bridget Heal, Professor of Early Modern History at the University of St Andrews

As a historian of Reformation Germany, I’m duty bound to say that the medieval period ended on 31 October 1517, the day on which Martin Luther supposedly nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg. Luther’s protest against the practices of the Catholic Church led to the splintering of western Christendom, to more than a century of religious warfare and, via some very circuitous routes, to the rise of religious toleration. Moreover, the German Reformation came of age alongside the printing press.

Of course, things weren’t that simple. Luther’s protest crystallised resentments that had been brewing for decades and there was much about his Reformation that was profoundly medieval. The deeply conservative Luther did not challenge the social or political status quo; that was left to his unruly spiritual offspring, the radical reformers. And it was not the newly formed Protestant churches but Catholic religious orders that shaped the other defining event of the age: European exploration and conquest.

The intellectual and cultural movement known as the Renaissance perhaps constituted another watershed. Humanist scholars certainly thought themselves to be living in a new age, set apart from the period of darkness that had followed the fall of Rome. Renaissance monarchs introduced new styles of kingship and there was a remarkable flourishing of art, architecture and music. But how much did the Renaissance really transform society? Bound by traditional social and economic structures, the lives of most of Europe’s inhabitants changed little. As Lord Blackadder memorably quipped to his servant: ‘To you, Baldrick, the Renaissance was just something that happened to other people, wasn’t it?’

Ultimately, periodisation is merely a device used by historians to structure their research and teaching. Within Europe the division between medieval and early modern was unclear and, beyond Europe’s borders, markers such as ‘the Reformation’ and ‘the Renaissance’ meant nothing. In this age of global history perhaps we need, therefore, to worry not about when the medieval period ended, but rather about whether it ever existed at all.

‘We cannot associate bigotry and credulousness with a vanished medieval past’

Lucy Parker, postdoctoral researcher at Christ Church, Oxford

The Middle Ages are a chimera, a fantasy, all but impossible to define or date, at least at a global level. The conventional chronological markers used to define them are deeply problematic: a start date of about AD 500, with the ‘fall’ of the western Roman Empire, and an end date of roughly 1500, with the cultural developments of the Renaissance, the European ‘discovery’ of the Americas and the religious dynamism of the Reformation. But most of these events took place in western Europe and do not work as chronological boundaries for the rest of the world. If we seek a global definition of the medieval, we cannot look to particular events; rather, we must identify a distinctively medieval character.

The Middle Ages are often defined by what the modern world is not – or, what we would like to believe the modern world is not. Whereas the modern world is global, secular, meritocratic and tolerant, the Middle Ages are seen as isolated, deeply religious, hierarchical and intolerant. None of this, however, straightforwardly characterises the period from 500 to 1500. Long-distance connections existed: take, for example, the Chinese Christian monk Rabban Sawma who in 1287 travelled as envoy of the Mongol khan to Europe, where he met dignitaries including Edward I of England. Persecution and intolerance were rife in some parts of the medieval world – notably Christian Europe from the 12th century onwards – but were not endemic everywhere. In the Abbasid caliphate the Islamic ‘Golden Age’ saw participation by influential Christians such as the doctor and scholar Hunayn ibn Ishaq (d.873). Hereditary kingship was not universal; the Byzantine emperor Justin I rose from lowly roots in the unfavoured Balkan provinces to become emperor of Constantinople. Religion held great importance, but people were not always unquestioning or gullible. In our modern world, which still sees religious and ‘ethnic’ conflict, the denial of rights for LGBTQ+ people, the neglect of refugees and the proliferation of misinformation, we cannot associate bigotry and credulousness with a vanished medieval past. If we define the Middle Ages in terms of prejudice and intolerance, then we must accept that we are still living in them today.

‘We move from “Old” to “Middle” English somewhere around 1066 or 1100 or 1150 or 1200 ...’

Elaine Treharne, Roberta Bowman Denning Professor at Stanford University

My History A-Level taught me that the medieval era ended on 22 August 1485, when the Welshman Henry VII established the Tudor dynasty. The Anglocentricity of this is all too obvious now, especially as this is really the point at which the ‘medieval’ emerged: when labels created by Renaissance writers eager to mark themselves out as new and sophisticated were superimposed onto a 1,000-year ‘middle age’.

I have worked within these western chronologies throughout my career as an ‘Old English’ scholar. In my field, categories move us from the ‘Old’ to the ‘Middle’ English period somewhere around 1066 (14 October at 4pm) or 1100 or 1150 or 1200 ... It’s an arbitrary boundary that has no purchase in the transformation of literature or the experiences of users of language. Within the Humanities, the labelling of periods is an administrative convenience, encouraging bite-sized modules to flesh out degree programmes.

For me, the medieval persists. Its influence and pervasive presence in art, culture, learning and society inform everything that came after. Where would literature be without the sonnet, first brought into English by Chaucer? Where would William Morris have been without the inspiration of the colours, patterns and writing of medieval manuscripts? How enriched contemporary culture is because of the work of Patience Agbabi, Zadie Smith, and Maria Dahvana Headley, each producing brilliant work that weaves new texts from medieval threads.

Such creative adaptations represent clear continuity of earlier traditions and are a far cry from the willfully ignorant appropriation of a false medieval by far-right groups: their distorted tropes of racial and ethnonational purity and misunderstood motifs and events attributed to an imagined past. For many cultures around the world, the ‘medieval’ never ended because it never existed. Within western culture, it never ended because it never really began.

‘When historians look for the end of the medieval era, they are really looking for signs of modernity’

Hasan al-Khoee, research associate at The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London

The historian Margreta de Grazia argues that the divide between what is considered ‘medieval’ and what is considered ‘modern’ has come to signify what is relevant to us today and what is not. When historians look for the ‘end’ of the medieval era, they are really looking for signs of modernity. Typically, they find it in the ‘Renaissance’, the imagined birthplace of modernity. I would suggest, though, that our perception of when the medieval period ended will always change as our own ‘modern’ identity evolves.

Another problem with this question is that ‘medieval’ commonly refers only to the Christian Latin-speaking lands of western Europe, excluding the Islamic world. The concept of ‘medieval’ was invented in 19th-century Europe, shaped by ideologies which drew something of an iron curtain between the Christian West and Islamic East.

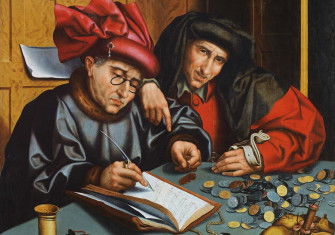

If anything, the idea of a ‘medieval’ era demonstrates the danger of periodisation. It warps our perceptions of history. Developments elsewhere are cut adrift: the emergence of Islam as the culmination of Late Antiquity in the seventh and eighth centuries; the centralised Caliphal states that followed; the Graeco-Arabic translation movements of the ninth century; the ‘classical’ age of the Islamic philosophical and scientific traditions which followed, that of al-Khawarizmi, al-Farabi, Ibn Sina (Avicenna), al-Razi, Ibn al-Haytham and Ibn Rushd (Averroes). From optics to Aristotelianism to astronomy, to architecture, chemistry and the mechanics of mercantile banking, developments in the Muslim world followed distinct histories periodised on their own terms. We now understand that such an approach does not work: the history of the Islamic world is inseparable from European history, especially the ‘birth’ of the Renaissance. By including the entirety of the Mediterranean in a revised concept of what medieval means, we may perhaps move away from the tired ideas of western culture’s death and rebirth. With our current image of the divide between the medieval and the modern, we deny the continuity of history.