The 50 Years that Made America

Fifty years separate the Boston Tea Party and the Monroe Doctrine. How did a group of British colonies become a self-proclaimed protector of continents within half a century?

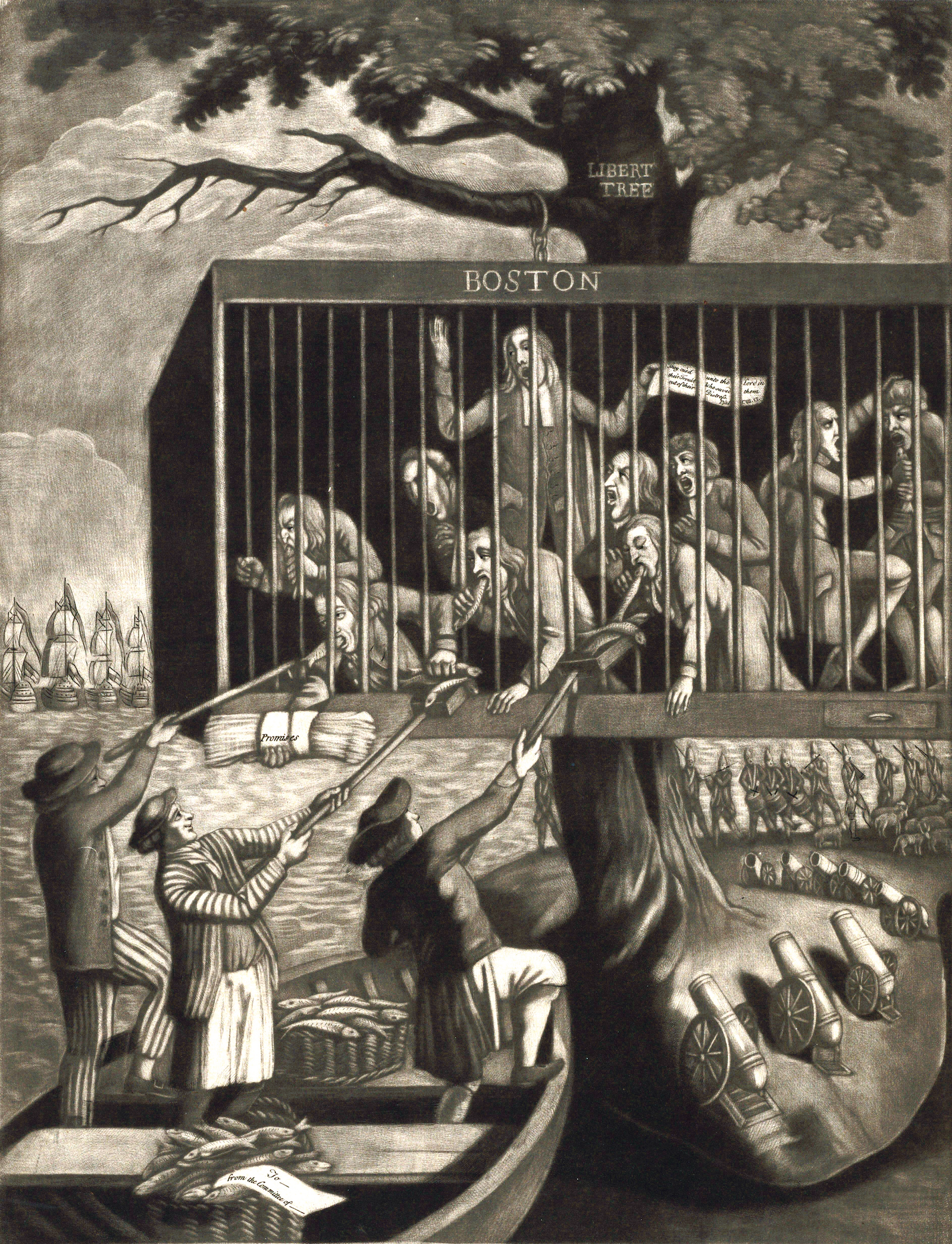

It was the evening of 16 December 1773. At Boston’s Old South Meeting House, more than 5,000 people awaited word from the governor of Massachusetts Bay, Thomas Hutchinson. Had the governor finally given in to their demand to send back to England the three ships laden with East India Company tea that were moored in Boston harbour? When learning of the governor’s refusal, tradition holds that the firebrand orator Samuel Adams loudly declared that ‘this meeting’ could do no more to defend the rights of the people. The words were a pre-arranged signal. Cries of ‘a mob, a mob’ broke out and a group of men disguised as ‘Narragansets’ or ‘Mohawks’ – local indigenous peoples – brandishing hatchets moved down the aisle of the church and out the south door. Joined by other men dressed up as ‘Indians’ they moved to Griffin’s Wharf where they boarded the ships Dartmouth, Eleanor and Beaver, hoisted their cargo of tea casks onto the deck, smashed them open and poured the leaves into the water. Some 90,000 pounds of tea worth £10,000 sterling was destroyed. Supported by a throng of onlookers, the brew masters took pleasure and pride in their handiwork. ‘We were merry, in an undertone, at the idea of making so large a cup of tea for the fishes’, one of them later recalled. Hutchinson was less impressed. He denounced the action as a ‘greater tyranny’ than any found in the Ottoman Empire, a shorthand for oppressive government. Such massive destruction of private property was unprecedented. Alluding to the disguise of the offenders, Hutchinson coldly remarked that: ‘Such barbarity none of the Aboriginals were ever guilty of.’

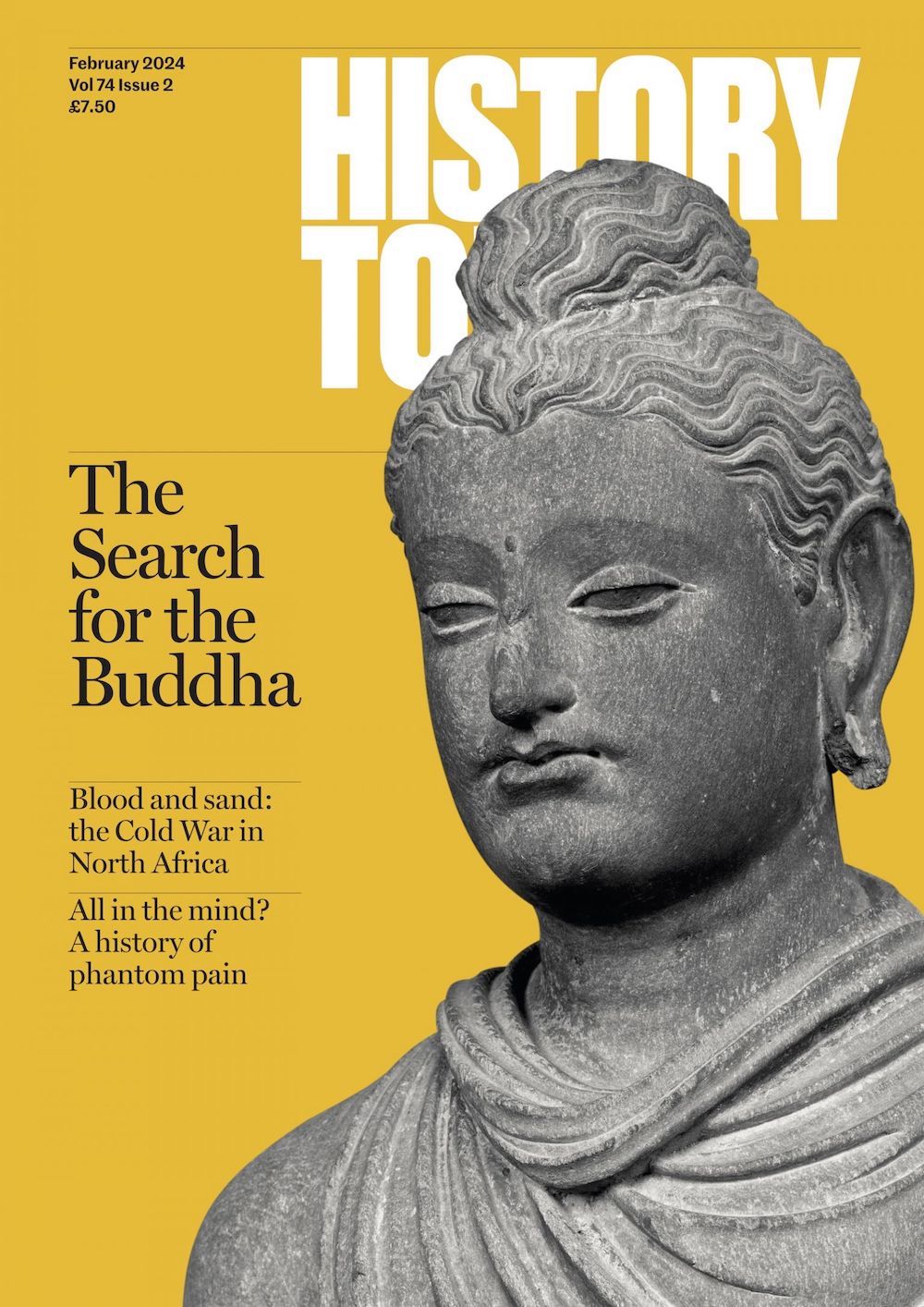

Half a century later, 400 miles to the south, a very different scene unfolded. On 4 December 1823, in a capital that was more construction site than city, and in a Capitol building barely restored after a British landing party had put it to the torch in the war of 1812, the US House of Representatives began debate on the president’s annual message. The precursor to today’s State of the Union Address, the message was presented in writing. On assuming the presidency in 1801, Thomas Jefferson had discontinued the practice of the president addressing a joint session of Congress because it resembled the British speech from the throne and smacked of monarchism. It was resumed only in 1913. The 1823 message was the labour of the cabinet of President James Monroe, who was fast approaching his final year in office. In a wide-ranging missive on domestic and international matters the president remarked, in words that would only later acquire their profound importance, that the American continents, north and south, were henceforth off limits to European colonisation. In Spanish America, the recent independence movement had created a string of new republics. Any European interference with these newly independent states, Monroe threatened, would be considered as ‘the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States’.

December 2023 marks the anniversary of these events. Fifty years apart, they bracket a period of state-formation and state-building unrivalled in modern history. The incident that contemporaries called ‘the destruction of the tea’ only became known as the Boston Tea Party half a century after the event. The affair aggravated an already strained relationship between Britain and its North American colonies and set in motion a chain of events that would lead to war and independence. The new nation that won independence in 1783 was a fragile construct beset by challenges that made the survival of the United States a most uncertain prospect. Monroe’s seventh annual message marked a turn for the better in the nation’s fortunes, exuding a new-found confidence arising from the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the subsequent implosion of the Spanish American empire. The ability to sail unharmed, if not untroubled, through the storm of the French Revolution and the ensuing quarter-century of global war told Europe’s great powers that the American ship of state was built to last. With a new Atlantic order in the making, the US was to play a leading part. Although the role as the arbiter of relations between Europe and the Americas was not within grasp in 1823, Monroe’s message would become an axiom of US foreign policy. Subsequent generations would know it as the Monroe Doctrine.

Revolution brewing

The Tea Party was but an episode in a drama that began with Britain’s attempt to manage the fallout of the Seven Years War (1756-63). Like other European empires, Britain had tried to bring its transatlantic colonies into closer orbit around the imperial sun. This meant taxing the colonies, improving the customs service and tightening control over imperial administration. Such reforms challenged a long tradition of de facto colonial autonomy, and from the mid-1760s the metropole’s and the periphery’s perceptions of how best to govern Britain’s sprawling Atlantic empire increasingly diverged. Ever since the deposition of James II in 1688, Parliament had been the sovereign power and the bulwark of popular liberty in the Kingdom of Great Britain. It was the duty of this representative assembly of the British people to keep executive power in check, and the British constitution placed virtually no limits on parliamentary sovereignty. But an arrangement designed to protect liberty in Britain became a problem when applied to the British Empire. America had no representatives in Parliament. Instead the colonies had their own representative assemblies, which functioned to all effects and purposes as Parliament did in Britain. If Parliament had the right to legislate for the colonies – for example by voting for taxes – it meant that Americans lived not under laws of their own making but were ruled by a distant and unaccountable government. In the inflated rhetoric of the 18th century, this made them no longer free but ‘enslaved’.

Between the end of the war and the destruction of the tea, the British government engaged in a process of trial and error to find a way to rule the colonies. When faced with resistance the government proved ready to back down quickly. In the cases of the Sugar Act (1764), the Stamp Act (1765) and the Townshend Duties (1767) Parliament had barely passed new legislation before it was amended or repealed. But if Parliament and the British ministry were willing to reconsider the viability of imperial policy, they never surrendered Parliament’s right to legislate for the colonies ‘in all cases whatsoever’. This principle was spelled out most clearly in a 1766 law with the telling title: ‘An act for the better securing the dependency of his majesty’s dominions in America upon the crown and parliament of Great Britain.’ At every step, the colonists protested British legislation with crowd action, organising boycotts, establishing local resistance committees and, in the case of the Stamp Act, co-ordinating American opposition in an inter-colonial congress. Whatever form dissent took, the aim was always the same: to defend colonial self-government

in domestic affairs from outside interference. Over time, the colonial position hardened. From having first accepted the right of Parliament to legislate on imperial affairs, such as trade regulations and import and export duties, colonial leaders came to challenge Parliament’s right to interfere in any way with the colonies’ right to self-government.

When the Townshend Duties were repealed in 1770, the import duty on tea was kept as a reminder of Parliament’s right to tax the colonies. Americans responded by boycotting the legally imported product and making smuggled Dutch tea their beverage of choice. This was the situation when, three years later, Lord North’s ministry set out to save the mighty East India Company from acute economic distress. High import duties and restrictions on re-exports had made tea expensive in Britain. Unsold tea accumulated in Company warehouses. Could the tea-loving North Americans be the solution? If the Company could sell directly to American consignees rather than to wholesalers in Britain, its tea could be priced to undersell smuggled tea even after the colonists had paid a modest import duty.

The plan looked perfect. But once more the government had failed to consider the American perspective. Neither colonial wholesale tea merchants nor colonial merchant-smugglers were pleased with an arrangement allowing East India Company consignees in colonial ports to corner the tea market. More ideologically motivated actors warned that should North’s scheme be made to work it would establish a precedent for parliamentary taxation of the colonies. Thus, trouble was brewing well before Company tea arrived in American ports. When it did, local leaders in New York, Philadelphia and Charleston staged protests, Company consignees resigned and in New York and Philadelphia the tea ships were forced to return their cargo to Britain. Only in Boston did the governor make the unloading of the tea a test of imperial authority.

Blood spilled

In a break with previous policy, the British responded to the Boston Tea Party with repression rather than accommodation. It was not the mob action that prompted this reaction. Before the advent of democracy, rulers on both sides of the Atlantic considered crowd action a legitimate way to register popular discontent. In recent memory, Boston mobs had protested imperial measures by sacking the lieutenant governor’s mansion, fighting off customs officers and assaulting army sentries. In each case, the government had hardly batted an eyelid. This time, however, there was colossal destruction of private property leading to a growing realisation that unless imperial authority was restored, control over the colonies might altogether slip away. ‘We must risk something’, Lord North said. ‘If we do not, all is over.’ In swift succession, Parliament closed and blockaded the port of Boston, dissolved the Massachusetts charter and made colonial officers the appointees of the governor rather than the assembly, allowed for criminal trials to be moved out of the colony, and provided for the bypassing of colonial assemblies when quartering imperial troops. In a parallel move, troops descended on Boston.

Massachusettsans had a reputation for being radicals. The North government hoped that by making an example of Massachusetts the American resistance movement could be defeated. This was yet another miscalculation. Instead of being passive onlookers the other colonies rallied to the support of Boston and Massachusetts. What soon came to be known as Parliament’s ‘Coercive Acts’ were interpreted as the first step in a programme to bring all American colonies under the sway of direct British rule. To counter this threat, delegates from 12 colonies met in the First Continental Congress in September 1774. They adopted a policy of non-importation of British goods and a threat of American non-exportation, called for the creation of local committees to enforce these policies and affirmed that, if Massachusetts were attacked, the other colonies would come to its defence. This happened much sooner than expected. In April 1775, a British army contingent marched out of Boston in search of reputed munitions stores and the leaders of the opposition. At Lexington and Concord they clashed with the Massachusetts militia. Shots were fired, blood was spilled. To the British thus began the American War. To the Americans it was the start of the War of Independence.

Critical period

It would be eight years before George III accepted that his erstwhile colonies were now 13 independent states. Years of war were also years of state-building. Born in a rebellion against the centralisation of authority, it was only natural that the new nation should take the form of a federal union that decentralised political power.

In the American state-formation process, the creation of a union was coeval with the declaration of independence. The first compact of union, the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was drafted in 1777 but took effect in 1781. The Articles served to protect member-states against an overbearing central government. But they made forceful foreign policy action difficult. This became apparent when the Continental Congress struggled to manage the War of Independence with energy and dispatch. It became clearer still when the war ended. The core function of any state is to protect the nation’s territorial integrity and interests. Under the Articles, the US could do neither. Congress could not enforce international treaties, including the peace treaty; it could not force the British to abandon military posts on US soil held contrary to the peace treaty; it could not adopt countermeasures against Britain’s discrimination against American shipping or Spain’s closure of the Mississippi River to American traders; it could not impose a common policy of international trade on the member-states; it could not prevent conflicts between member-states over interstate commerce and territorial boundaries; it could not service the nation’s foreign debt or secure new loans on good terms; it could not secure the loyalty of citizens in Kentucky and New England who contemplated secession; and it could not even retaliate against depredations on American trade in the Mediterranean by the so-called Barbary powers. Faced with a seemingly endless list of failures leading statesmen began to doubt the extent to which the US was a viable project.

Yet in the space of a few years, the fragile construct was replaced by a much stronger union that would make possible a more assertive tone in international affairs. Congressional weakness gave rise to a movement for stronger union that was crowned by success in the summer of 1787. Delegates to the Constitutional Convention held in Philadelphia crafted a new federal constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation and the member-states soon adopted it. Under the new Constitution, the states transferred important powers over taxation, diplomacy and war to the Union. The Constitution also created a tripartite central government that could legislate directly on individuals and implement its laws independently of the state governments. Of course, such centralisation of power ran contrary to the principles of the American Revolution. No wonder, therefore, that many have described the Constitution as a counterrevolution. But the reform did the trick. Under the leadership of George Washington the new federal government successfully began to address the various challenges that had plagued the US since the Treaty of Paris had officially ended the War of Independence in 1783.

A few months after the first Congress convened under the new Constitution, events took place that would culminate in the turmoil of the French Revolution. This upheaval soon spilled over in international wars of great magnitude, which imposed severe strains on the US. Had the American states not confirmed their commitment to union – and had they not transferred essential powers to the new central government – it is quite likely that the bands of union would have snapped and that the US would have broken apart. Between 1792 and 1815 the nation experienced recurrent war scares, engaged in an informal naval war against France in 1798 and fought Britain in the War of 1812. Yet when the dust settled on the battlefield of Waterloo, the US not only remained a federal union of republics, but had added five states to the Union and had doubled its landmass.

The Monroe Doctrine

Historians of the US sometimes mischaracterise the 19th century as an age of ‘free security’, when the nation could develop behind the protection of two vast oceans without fear of powerful neighbours. In reality, security concerns were always a factor in American political development. It is true that the international environment improved with the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars; nevertheless, there were challenges. After more than two decades of war, Europe’s great powers were exhausted and large-scale hostilities unlikely to resume. Britain had soundly defeated its maritime competitors France and Spain. Closer to home, the end of the Napoleonic Wars triggered an independence movement that ousted Spain from South America. These developments promised quieter times ahead for the Americas. The most likely disturbers of the peace were Austria, Prussia and Russia, which had formed the Holy Alliance to keep liberal movements in check. Morphed into the Quintuple Alliance by the addition of France and a much less enthusiastic Britain, the Alliance authorised interventions against liberal movements in Italy in 1821, Spain in 1823 and advised against the Greek rebellion in 1822. US statesmen feared that the Alliance had its eyes on the new South American republics, with plans to either recolonise the continent or set up puppet regimes.

James Monroe became the fifth US president in 1817. More than anything, his cabinet dreaded that a scramble for South America would bring the US new European neighbours. In the words of secretary of state John Quincy Adams:

Russia might take California, Peru, Chili [sic]; France, Mexico … And Great Britain, as her last resort, if she could not resist this course of things, would take at least the island of Cuba for her share of the scramble.

Delivered in 1823, Monroe’s seventh annual message did not set out to formulate a binding foreign policy doctrine. Instead, it applied shared ideas about US national interest to the threat of European intervention in America.

What became known as the Monroe Doctrine is, in actuality, a later construction that draws from three non-contiguous paragraphs of Monroe’s message. Three elements are central to the doctrine. First, the sharp division of the world into an eastern monarchical and western republican hemisphere. The president and the secretary of war, John C. Calhoun, were raring to go on an anti-monarchical crusade by declaring US support for radicals in Spain and Greece. Adams toned down the message to signal that the US would leave European affairs alone: ‘In the wars of the European powers in matters relating to themselves we have never taken any part, nor does it comport with our policy so to do.’ This move introduced the second and third elements of the doctrine, which declared the western hemisphere off-limits to European powers. In the non-colonialism clause, Monroe presented the principle ‘that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for colonization by any European power’. This was followed by the non-interventionist clause, which proscribed European attempts to overturn republican government in the Americas. According to Monroe, the European alliance could not:

extend their political system to any portion of either [American] continent without endangering our peace and happiness; nor can anyone believe that our southern brethren, if left to themselves, would adopt it of their own accord. It is equally impossible, therefore, that we should behold such interposition in any form with indifference.

Despite the pronounced anti-imperialism, the original message imposed no limits on US expansion into the homelands of indigenous peoples. Nor did it state any obligation on the US to come to the aid of sister republics in distress.

American policeman

Contrary to the boasts of the administration, Monroe’s message had no noticeable effect on European policy toward South America. The Alliance had no plan to intervene, nor would Britain have allowed them to. It was the Royal Navy, rather than a presidential decree, that kept Europe’s great powers at bay while prying open markets for international exchange. Monroe’s message began to be called a ‘doctrine’ only in the 1840s, in the context of US continental expansion that was facing possible British objections. The doctrine began to guide policy around 1900 when the US had become the principal power in the Caribbean basin. By that time, the Monroe Doctrine had metamorphosed into an interventionist policy. Theodore Roosevelt’s famous corollary cast the US as an ‘international police power’ with a duty to correct ‘chronic wrongdoing, or an impulse which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society’ in other countries. Before the Second World War, the American policeman was content to patrol the neighbourhood. With the Cold War, the beat became global. The demise of the Soviet Union only made US interventions more frequent. And so, in this year of American anniversaries, we are left contemplating the irony that a nation born in a rebellion against outside interference in the affairs of a self-governing people has become a state that, more than any other, intrudes in the business of foreign countries around the world.

Max Edling is Professor of Early American History at King’s College London.