Arguing with the Dead

Medieval historians are a small band. Departed greats such as James Campbell remain with us as long as we seek their opinions.

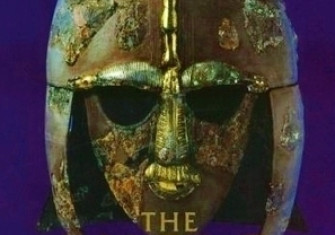

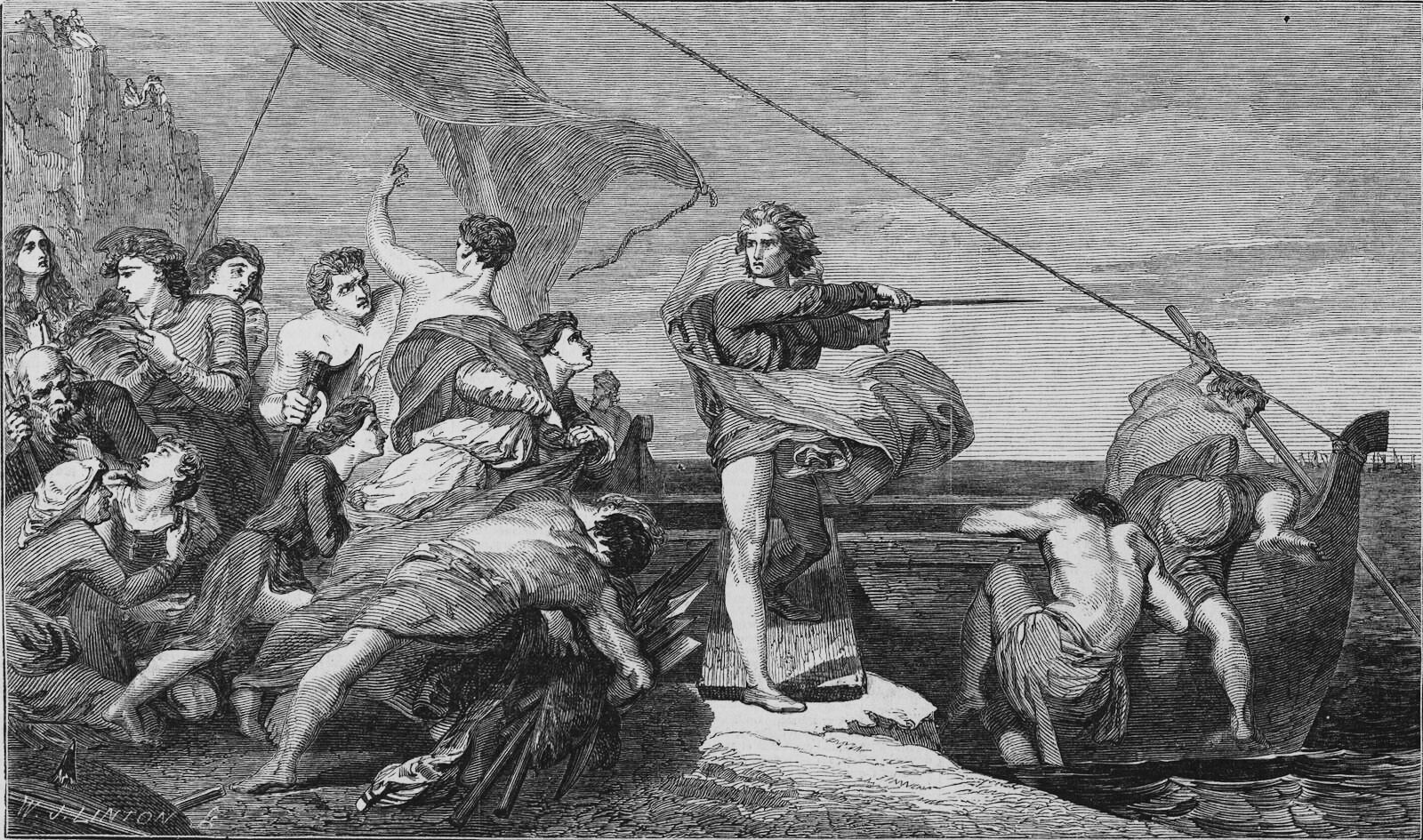

The dominating feature of Committee Room 10 in the Houses of Parliament is an enormous painting of King Alfred, by George Frederick Watts. Alfred, striking a heroic pose, is, in the words of the caption: ‘inciting the Saxons to resist the landing of the Danes’. Beneath this stirring scene, dedicated by the artist to ‘patriotism and posterity’, 100 Anglo-Saxon historians gathered recently to celebrate the projected publication of James Campbell’s Ford Lectures in British History. Delivered in 1996, Campbell had worked intermittently on them since; but on his death in 2016 they were left in some disarray. Their subject is ‘Origins of the English State’; and their uncompromising focus is on the Anglo-Saxon period, when, in Campbell’s view, the most important lineaments of the English state were laid down.

Even though Campbell never published a single-authored book, he is generally acknowledged to have been the most inventive and original Anglo-Saxon historian of the later 20th century. He inverted the consensus about what eventually became, well prior to the Norman Conquest, the English kingdom. No longer is it seen as primitive and increasingly decadent, deserving the coup de grâce administered in 1066; on the contrary, it developed a governmental system the sophistication of which was unparalleled in early medieval Europe. Campbell’s Ford Lectures represent the fullest statement of his mature views on the subject. The salvaging of several recensions of the texts from his deceased wife’s computer – Campbell was incapable of using one himself – is a cause for celebration. Their disappearance along with other unseen gems would have represented a catastrophic loss to Anglo-Saxon scholarship. It might be histrionic to suggest that it would have been commensurate with the fire in Ashburnham House in 1731, which destroyed sections of Sir Robert Cotton’s library; but by some it might have been regretted almost as keenly.

The gathering in Committee Room 10 consisted of pupils of Campbell (many of whom he inspired to devote their lives to his subject), colleagues and others he had influenced. There was amused reminiscing: Campbell’s celebrated quirks provide an inexhaustible fund of anecdotes. But papers were also delivered which reflected on and engaged with his work, especially the Ford Lectures and other hitherto unpublished pieces. He was not just an object of reverent affection, but of affectionate scholarly reverence. In subsequent discussion he was conjured in the minds of many as an interlocutor in the room, the person with whom everyone physically present was still arguing.

Those who have been major intellectual influences on us remain active presences in our minds ever after; on this score, their physical passing makes little difference. This is a familiar phenomenon in medieval historical scholarship, perhaps in part because, by comparison with other periods, we are a select band and most of us are at least vaguely acquainted. Also, the surviving evidence is fragmentary, very restricted and common to all. Everyone knows what everyone else is talking about. Those who are physically absent but still present to us communicate not only through their publications, but as we imagine what their views would have been on some new problem. Augustine does something similar when he ventriloquizes God in his Confessions. In that respect, the departed might be likened to dead parents whose voices we never cease hearing. But the phenomenon is not restricted to those we have known in person. Through their mediation, we become personally familiar with others we have encountered only through the medium of print. Campbell himself, in his final lecture, engaged with a number of now neglected 19th-century historians whom he could never have met, but whose pupils he had known. He regarded them as having much to contribute to his theme – indeed, far more than most recent historians.

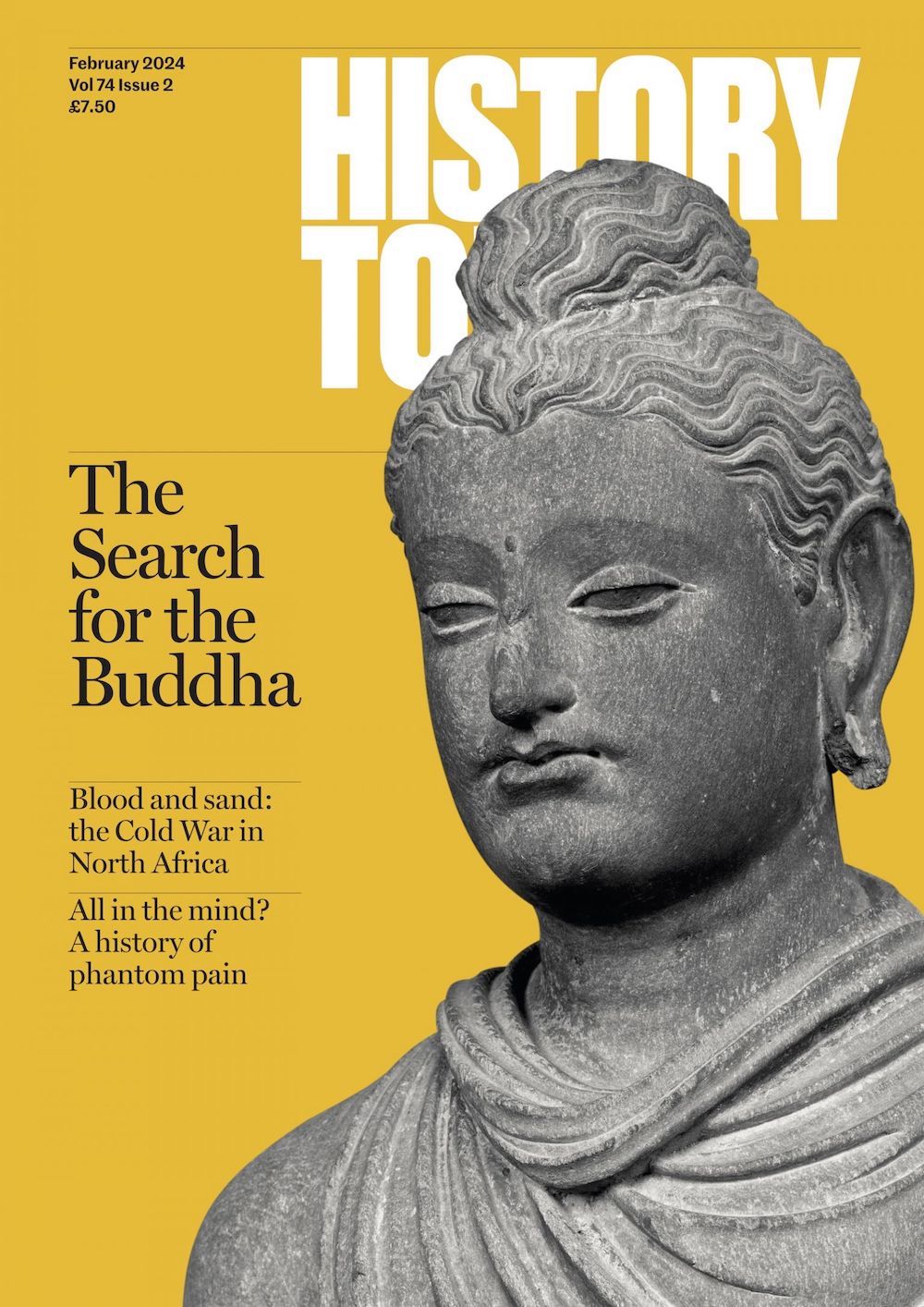

It is perhaps fitting that this phenomenon should be so apparent among medievalists, for it replicates many of the characteristics of a medieval monastery, as vividly described in contemporary histories and, particularly, hagiographies. These were also small communities, devoted, in one sense, to the intense contemplation of a limited, agreed set of texts. The dead – more accurately, those who had passed from mortal into eternal life – remained members of their community, which had a physical presence and living members in this world, but was in essence spiritual and transcendent. Its living members prayed for the souls of their departed brethren. They also, in the case of dead members deemed to be saints, might seek their intercession with the divinity on matters of current earthly concern. The sanctified dead were known to be occasionally active presences among the living, whose corporeal senses perceived them being so. Accounts of such supernatural interventions were scrupulously authenticated and recorded by eye-witness testimony, passed on by word of mouth over the years and even centuries, and eventually written down by historians and hagiographers. The analogy between the medieval monastery and modern historians of the Middle Ages is therefore not restricted to both communities encompassing the living and dead in some sort of dialogue, or at least communication, but is functional too, because in this particular sense both are engaged in the same sort of activity.

Committee Room 10 is intensely atmospheric, a manifestation of Pugin’s fantasy recreation of the Middle Ages – albeit Gothic, and therefore far later than the period on which Campbell focused. The chronological discrepancy was, however, utterly irrelevant that evening. He would have been particularly chuffed to be celebrated in the venue which houses Parliament, regarded by him as the lineal descendant of the Anglo-Saxon witan. With Alfred, the most appropriate king of all, presiding over the posterity to which his portrait was dedicated, it was possible to evoke James Campbell’s shade, and to articulate in communion the arguments which each of us has never ceased having with him.

George Garnett is Professor of Medieval History at Oxford University, Fellow of St Hugh’s College and the author of The Norman Conquest in English History: Volume I: A Broken Chain? (Oxford University Press, 2021). James Campbell’s Origins of the English State: the Ford Lectures and Other Essays, will be published next year by Shaun Tyas (an imprint of Paul Watkins).