Is Algeria Still Defined by its Liberation Struggle?

On the 60th anniversary of its end, Algerian memory of the War of Independence remains a thorny issue.

‘The war gave rise to an anti-colonial hyper-memory: one where the fallen are a constant presence’

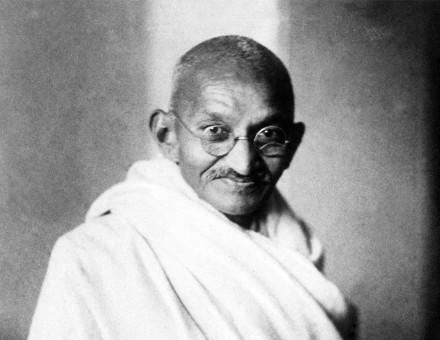

Martin Evans, Professor of Modern European History at the University of Sussex and author of Algeria: France’s Undeclared War (Oxford University Press, 2013)

Any answer must start with independence, when the anti-colonial struggle led by Algeria’s National Liberation Front (FLN) became the cornerstone of the new nation state. Inscribed in the 1963 constitution as a ‘war of one and a half million martyrs’, this sacrosanct status gave rise to an anti-colonial hyper-memory: one where the fallen are a constant presence, from monuments to street names, football stadiums and airports.

Contrast this with neighbouring Morocco. There, colonisation was much shorter, 44 years as opposed to 132 in Algeria. Morocco was always a foreign country under temporary French ‘protection’, while Algeria was a sovereign part of France. Consequently, in Morocco the colonial period is largely eclipsed by a longer narrative: the three and a half centuries old Alaouite Dynasty whose legitimacy is derived from this continuity and descent from the Prophet Mohammed.

In the first two decades after Algeria’s independence there was huge pride both in the anti-colonial victory and the fact that Algeria was a beacon of global anti-imperialism. During the 1980s that pride was tempered by scepticism as the younger generation, grappling with unemployment, became disillusioned. This was the moment when the idea of the false ‘war veteran’, inventing a glorious war record for nefarious gain, took popular root: an image of betrayal at the heart of much of the violence of the 1990s, when Islamist groups took up arms against the regime.

Today, colonialism is still a central part of public conversation, albeit with a new tinge. I was in Algeria just before Covid and was struck by how much anti-colonialism had become transformed into a more generalised anti-French feeling: the belief that France has not done enough to atone for colonialism, but also that the French link is still harmful, and that Algerians need to look elsewhere.

In this way anti-colonialism is still shaping Algeria. A point of comparison is perhaps Ireland where, 100 years on from independence, the contentious legacy of British rule still defines so much of Irish politics.

‘We should beware the tendency to interpret complex events purely through the lens of this struggle’

Rabah Aissaoui, Associate Professor of French and Francophone Studies at the University of Leicester

Observers of contemporary Algerian politics tend to argue that Algeria is still profoundly marked by the legacy of its anti-colonial liberation struggle. Of course, much attention has been paid to the War of Independence, fought between 1954 and 1962, yet Algeria’s fight for emancipation goes back much further; it includes the various insurrections and many acts of resistance against colonial violence, discrimination and dispossession suppressed by the French during the 19th century, as well as the repression of the uprising of the Constantinois region in 1945, which led to thousands of deaths. Despite this, we should beware the tendency to interpret complex socio-political developments and events in Algeria purely through the lens of this struggle.

As the French historian Pierre Nora argues, ‘History brings us together; memory divides us’. The history of Algeria’s long battle for liberation constitutes a contested terrain that is fought over in Algeria and France. On both sides of the Mediterranean histories of this struggle have been the subject of heated debates and tensions. As shown by Benjamin Stora, ‘memory wars’ between those affected by the War of Independence have continued to dominate public debate, yet they have largely failed to address the trauma and sense of grievance felt by many. Over the last six decades, rulers in Algeria have sought to establish and maintain their legitimacy by promoting what the historian Mohammed Harbi describes as a largely hagiographic narrative of the fight for independence. In France, as noted by Pierre Vidal-Naquet, the amnesty laws introduced by France after the war have shielded many French perpetrators and blocked any attempt for the victims to seek justice.

But the unresolved legacy of colonialism will not go away. Militant members of the Hirak, the mass protest movement for democratic reforms led by young Algerians since 2019, have frequently made reference to the struggle for anti-colonial liberation as an inspiration for their actions and to justify their demands for change. The issue of Algeria’s violent past is an active one.

‘A separatist movement is a legacy of French attempts to control the Algerian people through the divide et impera policy’

Belkacem Belmekki, Professor of History at Université d'Oran II, Algeria

Despite much more urgent concerns, such as severe unemployment and woeful living standards, Algeria’s colonial past still holds a special place in the hearts and minds of the country’s youth. The very mention of the struggle for independence still evokes images of torture and ruthless repression, transmitted through films, textbooks and orally by parents and grandparents who lived through it.

Unsurprisingly, France’s heavy-handedness in Algeria had a long-lasting impact on relations between the two countries, which can at best be described as complicated and which at times have been difficult. This is compounded by the adamant refusal of successive French governments to apologise for their country’s bloody past in Algeria. There are other issues, too, such as the status of Harkis (Algerians who had collaborated with the French), who wish to return to their home country. Neither the Algerian authorities, nor the population as a whole, seem ready to accept those who – 60 years on – they still regard as traitors.

Algerians hold mixed feelings towards France. Some continue to ascribe many of the country’s ills today to French rule more than half a century ago. The MAK (Mouvement pour l'autodétermination de la Kabylie) is an extremist movement, whose members seek independence for the region of Kabylia in northern Algeria. Though rejected by the overwhelming majority of Algerians, including by many Kabyles themselves, this movement is a legacy of French attempts to control the Algerian people through the divide et impera policy.

French rule in Algeria was, by all accounts, one of the harshest colonial systems recorded during the age of imperialism. The French left a deep scar on the psyche of the Algerian people and its marks are still visible on the generations who have grown up in an independent Algeria.

‘In July 2022 we are talking about a third generation that is using social media to shape its own narratives’

Nadja Makhlouf, Photographer. ‘El Moudjahidate, Invisible to Visible’ is available to view online.

What does anti-colonialism mean for Algerians and French citizens of Algerian heritage living in France after 1962? The question has impacted upon different generations in different ways, although each has grappled with two constants: endemic anti-Algerian racism within French society and official amnesia. Until 1999 the French government did not officially recognise the Algerian War as a full-scale war, but as an issue of ‘law and order’.

The first generation of Algerian migrants after 1962 did not talk about the war. The words ‘war’ and ‘colonisation’ were taboo. They tried to fit in as best they could and focused on their children, who were born on French soil and had the automatic right to French citizenship.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s there was a shift. This second generation was schooled in French republican values, while being brought up by Algerian parents, a duality which made them not quite Algerian and not quite French. This generation was confronted with the rise of the racist National Front and experienced a continuation of the colonialism and the racism endured by their parents and grandparents. Many were emboldened in their own anti-racist struggles by the memory of the anti-colonial struggle. For the first time, French children of Algerian origin became involved in politics. Through organisations like SOS Racisme, founded in France in 1984, they fought to be treated as equal citizens.

In July 2022 we are talking about a third generation that is using social media to shape its own narratives. This generation sees itself as the real bridge between the past and the present, denouncing the abuses committed by the French state and calling for an official recognition of these crimes. In the year which marks the 60th anniversary of independence it is still not easy to talk about the war, any more than it is easy to talk about the reasons why there was such violence: 132 years of colonisation. The subject remains thorny.

b1ab.jpg)