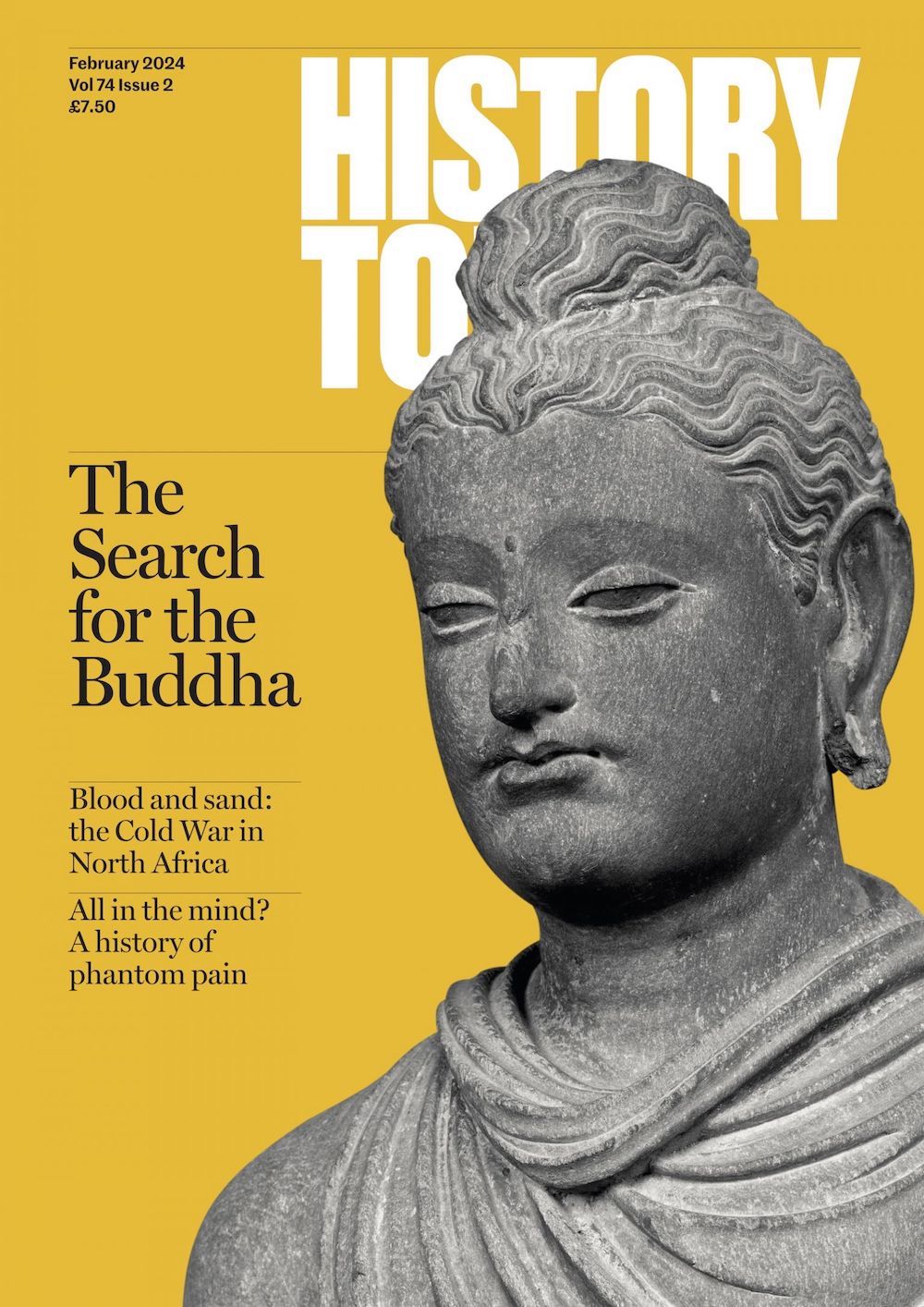

The Black Hole of Calcutta

Richard Cavendish describes how British prisoners were held captive by the army of the Nawab of Bengal, for one night, in the 'black hole' of Fort William in Calcutta.

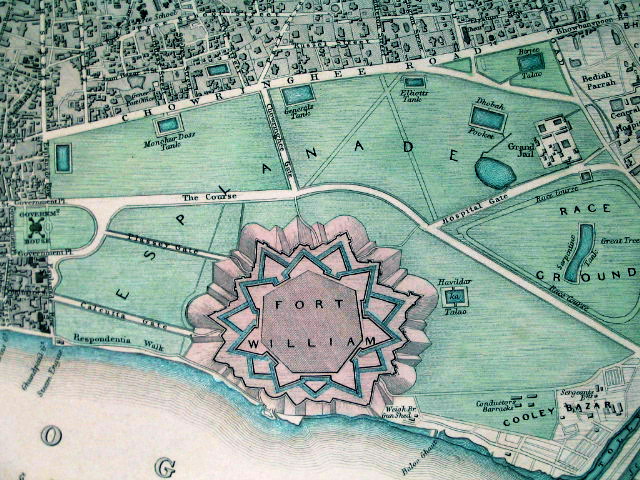

By the end of the seventeenth century effective power in the Mogul empire had fallen into the hands of the nawabs, or provincial governors, while the British and the French were building up their competing commercial empires in India. The British had established a port and trading base at Calcutta in the 1690s and built Fort William to guard it. Some years later they began to strengthen the defences against the French.

By the end of the seventeenth century effective power in the Mogul empire had fallen into the hands of the nawabs, or provincial governors, while the British and the French were building up their competing commercial empires in India. The British had established a port and trading base at Calcutta in the 1690s and built Fort William to guard it. Some years later they began to strengthen the defences against the French.

This offended the new Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-daula, who succeeded his grandfather in the capital of Murshidabad in 1756, when he was in his twenties. He sent orders to the governor of Calcutta to stop the work on the fortifications and when the British took no notice, the nawab marched on Calcutta with a massive army, said to have numbered 50,000 men with 500 elephants and fifty cannon. The army arrived on June 16th, and began to move slowly through the outlying areas of Calcutta, overwhelming all resistance. The governor and many of his staff and the British residents ran for safety to the ships in the harbour, leaving women and children behind and a garrison of only 170 English soldiers to defend the fort under the command of John Zephaniah Holwell, who was the Company’s zemindar, responsible for tax collection and keeping law and order.

There were two mortars in the fort, but much of the powder was too damp to use and the grapeshot had mostly been eaten by worms while in storage. Siraj’s final attack in force came on the morning of June 20th, a Sunday. Holwell had no military experience, the situation was hopeless in any case and by the afternoon he was forced to surrender in return for what he thought was a guarantee of quarter.

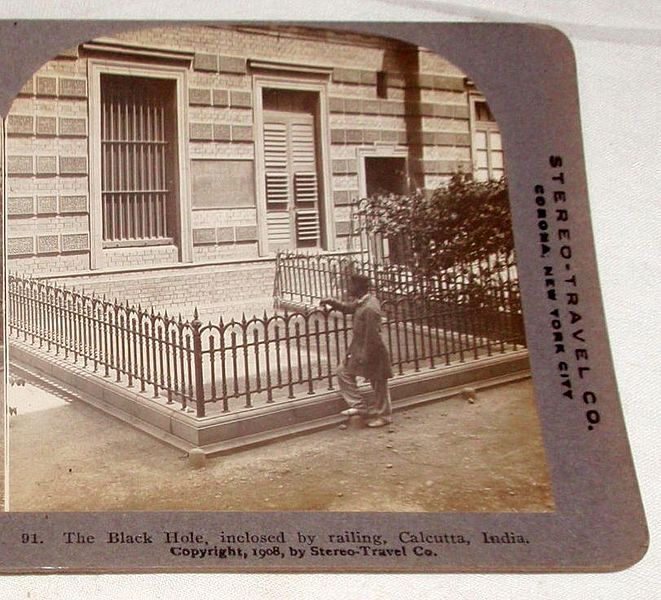

That night, as he recorded, there occurred a horror which became a legend in the history of the Raj. A total of 146 British prisoners, including two women and several wounded men, and Holwell himself, were herded at sword-point for the night into the fort’s ‘black hole’, a little lock-up the British had built for minor offenders. It measured only 18ft by 14ft 10in and had two small windows. The heat at that time of year was suffocating and the prisoners trampled on each other to get near the windows and fought over the small supply of water they had been left, while begging for mercy from the guards, who laughed and jeered at them while they prayed and raved in vain. At 6am the next morning when the door was unlocked, the corpses were piled up inside and only twenty-three of the prisoners were still alive. A pit was hastily dug for the dead and the bodies were dumped in it.

That night, as he recorded, there occurred a horror which became a legend in the history of the Raj. A total of 146 British prisoners, including two women and several wounded men, and Holwell himself, were herded at sword-point for the night into the fort’s ‘black hole’, a little lock-up the British had built for minor offenders. It measured only 18ft by 14ft 10in and had two small windows. The heat at that time of year was suffocating and the prisoners trampled on each other to get near the windows and fought over the small supply of water they had been left, while begging for mercy from the guards, who laughed and jeered at them while they prayed and raved in vain. At 6am the next morning when the door was unlocked, the corpses were piled up inside and only twenty-three of the prisoners were still alive. A pit was hastily dug for the dead and the bodies were dumped in it.

Holwell referred to the experience as ‘a night of horrors I will not attempt to describe, as they bar all description’, which did not prevent him describing them at length and in detail after his return to England the following year, in A genuine narrative of the deplorable deaths of the English gentlemen and others, who were suffocated in the Black Hole. In the majestic prose of Macaulay’s essay on Clive of India, based on Holwell’s account, the story inspired patriotic fervour and rage at Indian perfidy in generations of Britons. It has long been clear that Holwell’s figures were exaggerated.

According to a calculation by Professor Brijen Gupta in the 1950s, the total of prisoners shut in the black hole was probably sixty-four, of whom twenty-one came out alive. He also produced evidence that Siraj-ud-daula did not order the prisoners to be shut in the black hole and knew nothing about it until afterwards.

Vengeance was swift. Robert Clive marched on Calcutta and set siege to Fort William, which was also bombarded by an accompanying fleet of warships under Admiral Charles Watson. The fort fell to the British in January 1757 and in February with an army of a mere 3,000 men, Clive routed Siraj’s army of perhaps 50,000 with their cannon and war-elephants at Plassey.

Siraj fled to Murshidabad, where he was killed by his own people and his body thrown into the river.