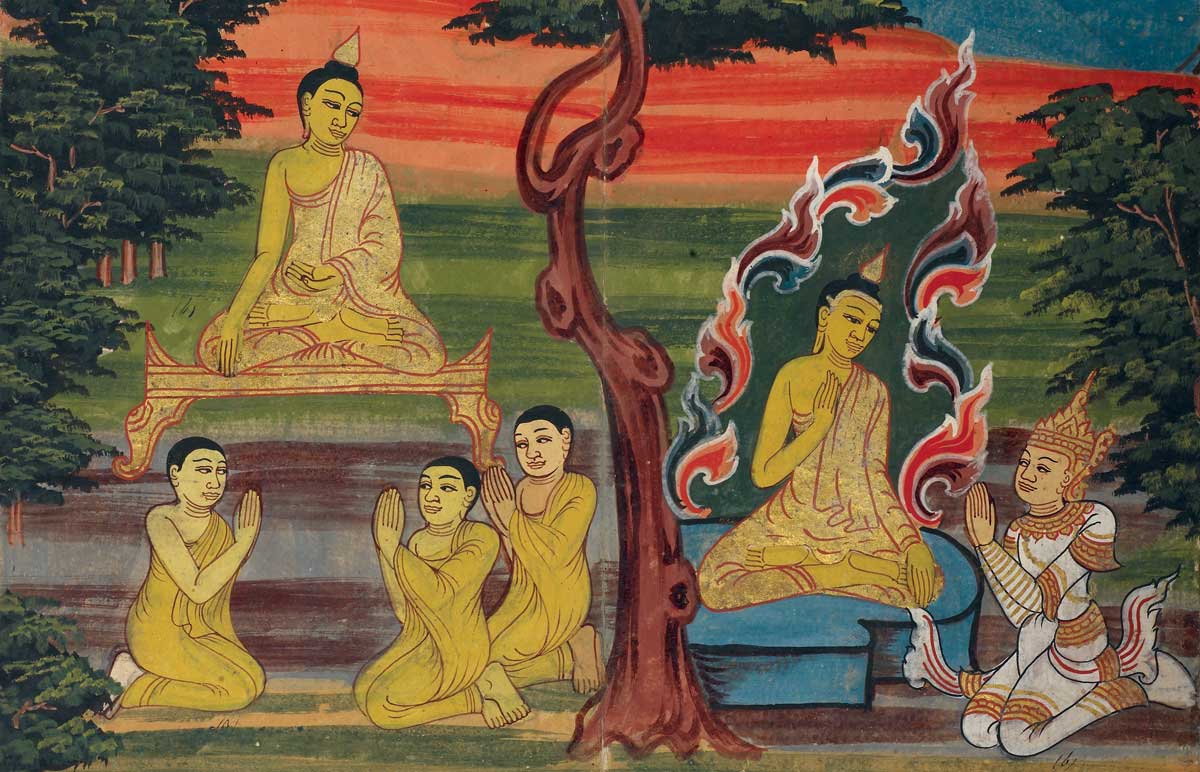

Devadatta in Hell

One of Buddhism’s most reviled villains was crucified in the Buddhist underworld. When French Christians arrived in Siam in the 17th century, venerating images of Christ on the cross, dialogue between the two religions reached an impasse.

In the stories of the Buddha’s life there are two villains. The first is Mara, the Buddhist deity of desire and death. Fearing that if Prince Siddhartha achieved buddhahood he would deprive him of victims, Mara attacked the prince under the Bodhi Tree. He failed. The other villain is Devadatta, the Buddha’s cousin. To exalt the Buddha, one must debase Devadatta. To debase the Buddha, one must exalt Devadatta.

After his enlightenment in the sixth or fifth century BC, the Buddha, then aged around 35, returned to his home city of Kapilavastu, now in Nepal. Several of his relatives joined the order of monks, including two of his cousins: Ananda, who would later become the Buddha’s personal attendant, and Devadatta, who would become the Buddha’s chief antagonist and one of the most reviled figures in the history of Buddhism. Yet, Devadatta seems to have been a dedicated monk for decades, praised for his practice of meditation. It was when the Buddha grew old that the trouble began. When the Buddha was 72 (he would die, or ‘enter nirvana’ at 80), Devadatta politely suggested that, in light of the Buddha’s advanced age, leadership of the order of monks should be turned over to him. The Buddha refused, adding, in one of the less compassionate statements in the canon, ‘Why would I turn over the order to a clot of spittle like you?’

Smarting from this humiliation, Devadatta plotted to assassinate the Buddha. First, he hired 31 archers to kill him, but the Buddha converted them all. Next, Devadatta pushed a large boulder down Vulture Peak, the Buddha’s favoured retreat near Rajagriha, but large outcroppings miraculously emerged to block its path; a splinter broke off and struck the Buddha’s toe, causing it to bleed. Finally, he sent the great bull elephant Nalagiri, made drunk on palm wine, to trample the Buddha. But when the elephant reached the Buddha, the beast knelt down and the Buddha stroked his head, a scene that is widely depicted in Buddhist art.

Foiled

Despite these dastardly deeds, Devadatta remained in the order of monks. Seeking to challenge the Buddha’s commitment to asceticism, he recommended that all monks should follow five rules: they should live in the forest and not in villages; they should live on alms and not accept invitations to dine in the homes of the laity; they should only wear robes made from discarded rags and not accept offerings of new cloth; they should dwell at the foot of a tree and not under a roof; they should not eat fish or meat. The Buddha declared that any monk who wished to obey these rules was free to do so, but he would not make them obligatory. Devadatta denounced the Buddha for his laxity, gaining a following of newly ordained monks, who departed with him. However, the Buddha sent two of his senior monks after them and the new monks soon returned. Devadatta vomited blood on hearing the news.

Perhaps it may be wise to pause here and consider Devadatta’s suggestions, each of which seems rather reasonable, even expected, for a Buddhist monk as he is usually imagined in the West. We might find it hard to imagine monks eating meat at lavish lunches (never dinner, since monks take a vow not to eat after midday) at the homes of the rich and famous. Yet scholars of Buddhism have since speculated that, though there were monks who found such practices wrong and argued for a more spartan lifestyle which they themselves followed, there was also opposition to such demands. Indeed, one argument suggests that this hostility was so great that the well-dressed carnivore majority concocted the story of Devadatta (which is the Sanskrit equivalent of ‘John Doe’) to discredit the ascetic practices by tracing them back to the person who tried to kill the Buddha.

Bad karma

Knowing that his own end was near, Devadatta set out to see the Buddha one last time. According to some accounts, he had finally seen the errors of his ways. According to others, he smeared poison on his fingernails for one last assassination attempt. As he sat by a pond where he had stopped to bathe, he was slowly swallowed by the earth. When only his head remained and his jawbone touched the ground, he declared:

With these bones, with these vital airs,

I seek refuge in the Buddha,

Preeminent among men, god of gods, charioteer of untamed humanity,

All-seeing, endowed with the auspicious marks of a hundred virtues.

But his repentance came too late, his karmic burden was too heavy, dragging him down to Avici (‘Incessant’), the most horrific of the 16 Buddhist hells (eight hot, eight cold). It is located at the greatest distance beneath Bodh Gaya (the place where the Buddha achieved enlightenment), with the longest lifespan and the most excruciating sufferings; the bodies of its denizens become indistinguishable from a fire that never goes out. All that remains is their voice.

According to Buddhist doctrine there are five deeds that cause rebirth in Avici without an intervening lifetime in another realm: killing one’s father, killing one’s mother, killing an arhat (an enlightened person destined for nirvana), wounding the Buddha and causing dissent in the monastic community. Devadatta had committed the fourth and fifth. When a nun berated him for his assassination attempts, he beat her to death. Because she was an arhat, he also therefore committed the third. As a consequence, Devadatta suffered a particularly horrific fate in hell. His body grew to be 100 leagues tall, his head locked in an iron helmet touching the top of the vast chamber of Avici. His feet sunk up to his ankles in its surface of solid iron. Then, as one text explains:

An iron stake as thick as the trunk of a palmyra tree proceeded forth from the west wall of the iron shell, pierced the small of his back, came forth from his breast, and penetrated the east wall. Another iron stake proceeded forth from the south wall, pierced his right side, came forth from his left side, and penetrated the north wall. Another iron stake proceeded forth from the top of the iron skull, pierced his skull, came forth from his lower parts, and penetrated earth of iron. In this position, immovable, he suffers this mode of torture.

Devadatta was thus impaled for aeons.

Devil worship

In 1687 the French ‘Sun King’ Louis XIV sent an embassy to Siam led by the polymath and diplomat Simon de la Loubère. Upon his return to Paris, de la Loubère published his acclaimed De royaume de Siam, translated into English in 1693 as A New Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Siam. In it, one is surprised to find a lengthy biography of Devadatta, apparently commissioned by de la Loubère, entitled ‘The Life of Thevetat, Translated from the Balie’ (that is, Pali, the canonical language of Thai Buddhism). Here, Devadatta is Thevetat, Avici is Avethi and the Buddha is Sommona-Codom, an approximation of one his epithets, Samana Gotama, ‘the ascetic Gautama’. But otherwise, the rendition is quite faithful:

Mean while Thevetat was buried in the Earth, and even to Hell where he is without possibility of removing, for want of having loved Sommona-Codom. His Body is the heighth of a Jod, that is to say, Eight Thousand Fadom: he is in the Hell Avethi, 650 Leagues in greatness: on his head he has a great Iron pot all red with fire, and which came to his Shoulders: he has his Feet sunk into the Earth up to the Ankles, and all inflamed. Moreover a great Iron Spit which reaches from the West to the East, pierces through his Shoulders and comes out at his Breast. Another pierces him through the sides, which comes from the South, and goes to the North, and crosses all Hell. And another enters through his Head, and pierces him to the Feet. Now all these Spits do stick at both ends, and are thrust a great way into the Earth. He is standing, without being able to stir, or lye down.

Why would the French be interested in the story of Devadatta? Alexandre, chevalier de Chaumont was the first ambassador sent to Siam by Louis XIV. In the account of his embassy of 1685 he briefly describes the religion of Siam, calling the Buddha Nacodon (an abbreviation of Sommona-Codom). Referring to Devadatta, he writes: ‘In short, his Brother was thrown into Hell for his great sins, where Nacodon caused him to be crucified; and for this foolish reason they abominate the Image of Christ on the Cross, saying we adore the image of this Brother of their God, who was crucified for his Crimes.’

The French party included the Jesuit Guy Tachard, who provides a detailed description of the life of the Buddha, in the course of which he laments the connection with Devadatta:

Tho there be many things that keep the Siamese at a distance from the Christian Law, yet one may say, nothing makes them more averse from it than this thought. The similitude that is to be found in some points betwixt their Religion and ours, making them believe that Jesus Christ, is the very same with that Thevathat mentioned in their Scriptures, they are perswaded [sic] that seeing we are the Disciples of the one, we are also the followers of the other, and the fear they have of falling into Hell with Thevathat, if they follow his Doctrine, suffers them not to hearken to the propositions that are made to them of embracing Christianity.

As Tachard wrote, the conflation of Christ with Devadatta was proving insurmountable:

That which most confirms them in their prejudice, is that we adore the image of our Crucified Saviour, which plainly represents the punishment of Thevathat. So when we would explain to them the Articles of our Faith; they take us always up short, saying that they do not need our Instructions, and that they know already better than we do, what we have a mind to tell them.

This may explain why Simon de la Loubère asked for a Pali account of the life of Devadatta. Giving new meaning to ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend’, the French may have felt that they might learn something from the life of the Buddha’s antagonist, as they sought to convert the Siamese to the true faith.

Suspicious minds

The Thai suspicion of the French was not unfounded. Devadatta’s sin was vanity. He did not doubt the efficacy of the Buddha’s teachings, nor did he deny that the Buddha was the enlightened one. He simply wanted to succeed him as the head of the order after the Buddha had grown old. The proselytisers who came from Europe were far more pernicious. Wearing crucifixes around their necks, they declared the teachings of the Buddha to be a lie, insisting that Buddhists reject them and worship the one who had suffered the fate of Devadatta.

So suspicious were Europeans of Buddhists that the Scottish surgeon and botanist Francis Hamilton would claim that the story of Devadatta had been concocted by the adherents of Buddhism after the arrival of Vasco da Gama in India in 1498 to prevent conversion to Roman Catholicism. In his essay, ‘On the Religion and Literature of the Burmas’, published in Asiatick Researches in 1801, Hamilton explains all this, unable to resist providing a dig at the Catholics at the end:

The Siammese painter before-mentioned told me, that Devadat, or, as he pronounced it, Tevedat, was the god of the Pye-gye, or of Britain; and he conceived, that it is he who, by opposing the good intentions of Godama, produces all the evil in the world. I am inclined to believe, that the legend of Tevedat, of which M. Loubere has given us a translation, has been composed since the arrival of the Portuguese in India, in order to prevent the propagation of [the French] religion, so well adapted, by its splendour and mysteries, to gain the belief of an ignorant people.

We can only imagine what the august Buddhist monks at the royal court of Siam must have thought as the French delegation approached the throne, their priests wearing little statues of Devadatta around their necks. Even if the Buddhist case of crucifixion had not involved the monk who tried to murder the Buddha, Buddhists are likely to have found it odd that anyone would honour a being who had suffered such a fate. What horrible deed could he have committed to deserve that punishment? And, if he was a being worthy of worship, why did he lack the powers to escape the cross? At that early point in the history of Buddhist-Christian dialogue, it is unlikely that the fine points of the theology of the Lamb of God could have been conveyed effectively from French into Thai.

Crossed wires

Might a more constructive dialogue on salvation and damnation between the French Christians and the Thai Buddhists have been possible? Perhaps. Let us end by considering a theory put forward by the Swedish theologian Nils Runeberg of the University of Lund in his 1904 book Kristus och Judas. Runeberg elaborated on the view of the English essayist Thomas De Quincey, who had argued that Judas had betrayed Jesus in order to force him to declare his divinity and spark the rebellion against Rome. Runeberg argued that Judas’ betrayal of Jesus was an act of profound theological significance, because it served as the cause of the crucifixion and resurrection. The Romans clearly knew who Jesus was; there was no need for Judas to identify him. But in order for Jesus to be exalted, Judas must be condemned; in order for Jesus to ascend into heaven, Judas must descend into hell. And he must descend as the result of an irredeemable sin. So, the French might have explained, Devadatta was Judas, not Jesus, both religions sharing this debased antagonist. With common ground established, Jesuits in China and Japan might have learnt that, in the 12th chapter of the Lotus Sutra, the Buddha predicts that even Devadatta will one day become a buddha …

But this was always unlikely. Runeberg’s theory was first published in ‘Tres versiones de Judas’, a 1944 short story by Jorge Luis Borges. By the time Borges invented Runeberg, the European encounter with Buddhism already had its own long history of misunderstanding.

Donald S. Lopez Jr. is the Arthur E. Link Distinguished University Professor of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies at the University of Michigan.