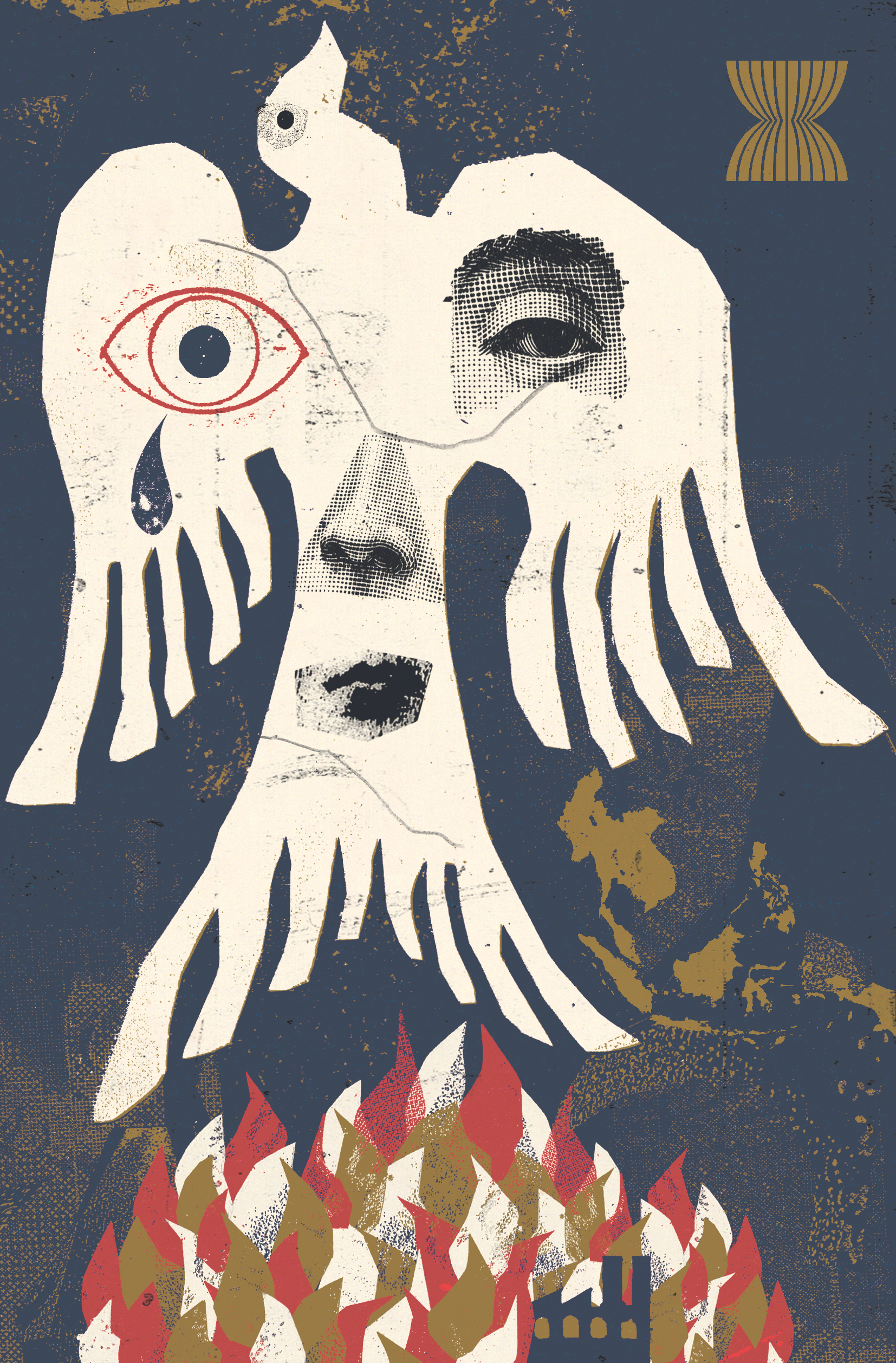

How ASEAN Lost its Way

ASEAN was founded to promote peace between the nations of Southeast Asia. Incapable of moving with the times, what is the point of it?

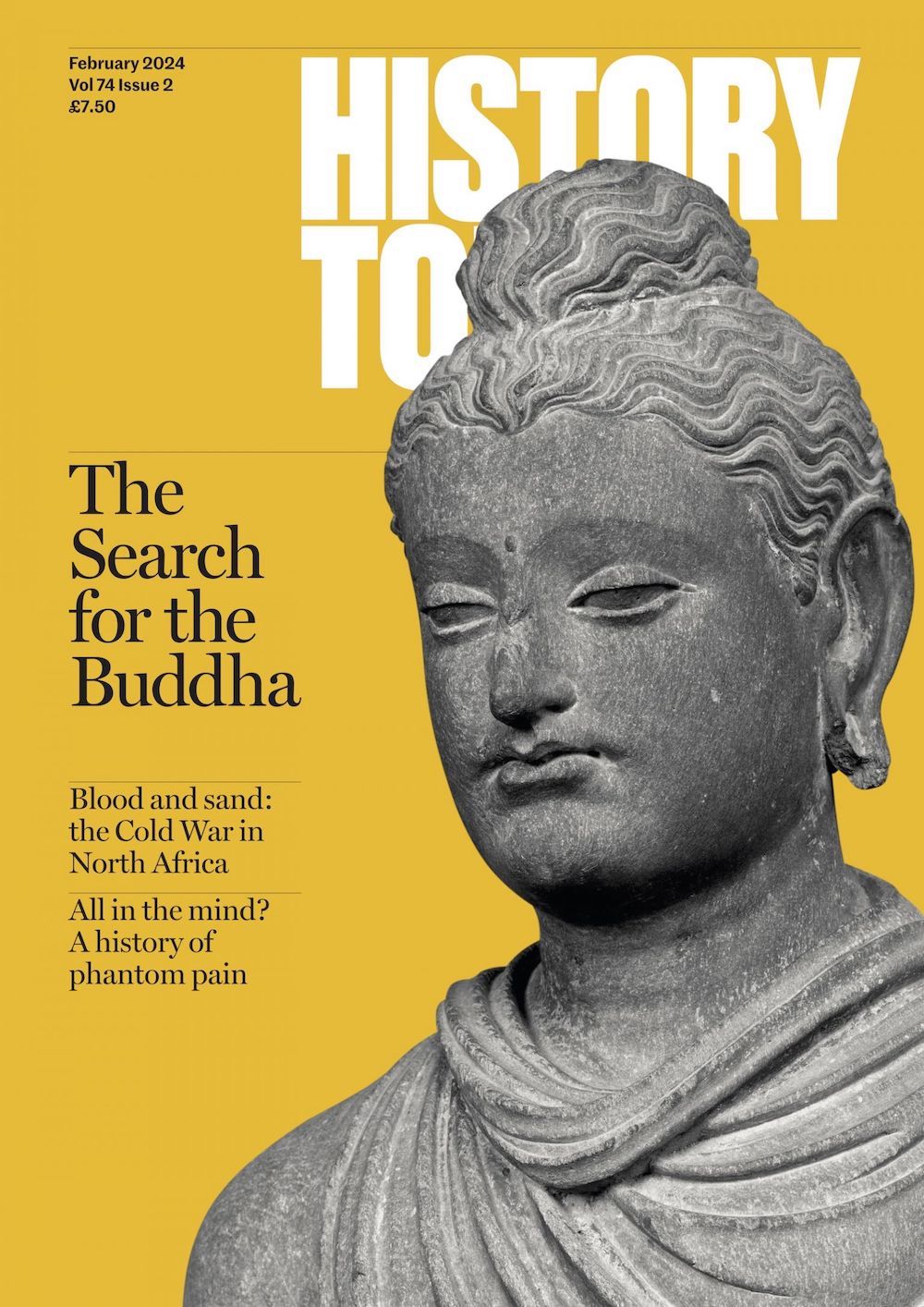

Southeast Asia is a sprawling region spread out between the Indian Ocean to the west and the Pacific to the east, China to the north and Australia to the south. It is home to 675 million people and to the world’s busiest shipping lane. Nearly 100,000 vessels pass yearly through the Malacca Strait, a narrow stretch of water between Malaysia and Indonesia that links Europe, India and the Middle East to two of the world’s largest economies, China and Japan. In the current contest between China and the US, Southeast Asia has become a battleground once more, reprising the role it played during the Cold War, when China, Soviet Russia and the US fought for control in proxy wars across the region, in the process laying waste to Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

Fifty years ago the region was alive with anti-colonial, nationalist and communist movements, with an underground of revolutionaries and their foot soldiers stirring discontent. The political vacuum left by the Japanese and Western colonial forces was quickly filled by local actors and their international sponsors. In this new world, political promiscuity was a means of survival. Vietnam’s Communist Party courted both China and Russia before it had to choose. Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge regime, a creation of communist Vietnam, later betrayed it for China. The grassfire of communist insurgency burned on the mainland as well as the islands. Race and political riots broke out in Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, where it is estimated that around 600,000 supposed communists were murdered under President Suharto in 1965-66. In this turbulent milieu the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, was born.

Peace and war

On 8 August 1967 the leaders of Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines and Indonesia met in Bangkok and launched the association as we know it today. ASEAN was created with the intention of promoting peace between members: Indonesia and Malaysia had only recently concluded their ‘Konfrontasi’; Malaysia and the Philippines their conflict over Sabah in northeast Borneo. ASEAN was also envisioned as a club to foster economic growth and foil foreign intervention.

In the 1990s ASEAN membership expanded to complete the whole grouping of Southeast Asian countries, offering four previously isolated mainland states a route to political membership of the international community: Vietnam (1995), Myanmar (1997), Laos (1997) and Cambodia (1999).

Integrating four authoritarian and (post-) communist states into a consensus-based association was always likely to cause problems. A glance at the situation in 2024 shows what they are. Almost 60 years after it was founded, what is ASEAN good for? Maintaining peace? Look at the situation in Myanmar. Political stability? Look at Thailand and Malaysia. Vietnam resembles a Stalinist country, while authoritarian Cambodia is practically a feudal system. Singapore is a one-party state. ASEAN has been a disaster for the mainland countries, supporting both the American War in Vietnam and, then, Pol Pot’s genocidal Khmer Rouge in Cambodia (as did, it should be remembered, the UN).

It is the ongoing situation in Myanmar that lays bare ASEAN’s failings most starkly. On 1 February 2021 the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military, launched a coup, imprisoning elected members of parliament and forming the State Administration Council (SAC). The coup was universally rejected by Myanmar’s populace. Hundreds of thousands took to the streets in protest; the army responded by mowing them down. Urban youth mobilised in the cities; others fled to ethnic minority areas in the north for military training. The past three years have seen desperate cycles of junta airstrikes, resistance attacks, economic decline and human suffering.

International response to the Myanmar crisis has simultaneously acknowledged ASEAN centrality – that ASEAN should lead the response – while pouring scorn on the organisation’s credibility. In 2021 ASEAN agreed a Five-Point Consensus, meant to facilitate the return of stability in Myanmar. The SAC ignored it. Despite being seen as the natural regional actor to bridge the diplomatic gulf between the military junta and the outside world, ASEAN has had little success over the last three years, or even the past three decades. Its ‘constructive engagement’ approach has seen scant change in Myanmar, where the military has grown more and more egregious.

The Way

In the face of this, ASEAN leaders continue to champion the ‘ASEAN Way’, shorthand for the association’s much-mythologised principles of non-interference, quiet diplomacy, non-use of force, and decision-making through consensus. Even when ‘the Way’ has been found wanting, as in Myanmar, it has never been up for serious appraisal or reform. For more than half a century the Way has preserved the status quo, even when failures stare it in the face.

Three explanations are often cited for ASEAN’s failure on Myanmar. One, its members have divided interests: the mainland states privilege stability, order and non-interference, while the maritime states push for dialogue, reconciliation and political reform. Two, ASEAN has no leverage over the military junta. There are no geostrategic, economic or military carrots and sticks to be brandished. Three, the consensus-based ASEAN Way inhibits decision-making, particularly when a minority of members are partial to Myanmar’s SAC.

These explanations, however, let ASEAN off too easily. They might explain the lack of progress, but they don’t explain the paucity of effort or urgency. They ring defeatist, emphasising structural impediments and absolving ASEAN of the responsibility to meaningfully try. Myanmar could represent an opportunity to reform the Way through precedent, adapting ASEAN’s charter by practice. But an absence of imagination in statecraft, plus a reluctance to tackle difficult issues, reduces the organisation to nothing more than a ‘talkfest’.

Fear of change

Aside from Myanmar, there is also the issue of simmering tensions between some ASEAN nations and China over the South China Sea. Since the non-binding Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in 2002, two decades of negotiations between ASEAN and China have yielded no agreements and little prospect of reducing the potential for conflict. How did stasis come to define the ASEAN Way?

One answer might be that ASEAN itself is fearful of change. Bilahari Kausikan, a Singaporean diplomat and one of the organisation’s more forceful defenders, argues that because the nations of Southeast Asia are ruled by the ‘permanent conditions’ of race and religion, the ASEAN Way of managing these conditions, as established at its founding, must not be abandoned or tinkered with. The problem here is that the world has changed, and so has Southeast Asia. The values and norms that held countries together 50 years ago are different today. The appropriate solutions for Southeast Asians back then might not be right today.

A case in point is the environment. In the 1960s and 1970s, awareness of the existential threat posed by the burning of fossil fuels was much lower than it is now. At the recent UN climate change conference in Dubai, fossil fuels were cited – for the first time – as the root cause of the crisis. The call to action to reduce carbon emissions and limit global heating is international because the effects of climate change transcend borders and states. How does this square with the ASEAN Way?

The short answer is: it doesn’t. Problems such as the expansion of coal power stations and the choking haze of burning forests in Indonesia, deforestation in Cambodia, construction of massive dams in Laos and uncontrolled use of plastic across the region transcend boundaries as well as race and religion. As temperatures and sea levels rise, the effects are felt from the Mekong Delta to the Malacca Strait. Theoretically speaking, the climate crisis can’t be effectively tackled in the ASEAN Way, since asking any one country to do something could mean interfering in its internal affairs. For this reason ASEAN has no meaningful programme to address the single biggest threat to life in Southeast Asia. The organisation’s blueprints for climate action are full of tired and empty slogans about promoting public awareness.

Business as usual?

As Laos, the least developed and outspoken of the ASEAN countries, assumes the ASEAN Chairmanship in 2024, one could be forgiven for expecting business as usual. This year Indonesia, a pivotal country not only because of its size but also because of its founding role, goes to the polls. If, as Kausikan reminds us, ‘Where Indonesia goes, ASEAN must ultimately follow’, then the region is heading for more stasis. Prabowo Subianto, the defence minister and former army general, is now streets ahead of his nearest rivals and is predicted to succeed Joko Widodo. Given his profile and record, Prabowo seems unlikely to push ASEAN reform.

But ASEAN shouldn’t just be about its political leaders. More than 600 million people make up the region. Peoples’ movements in Thailand, Myanmar and Malaysia in recent times have shown Southeast Asians to be committed in their efforts for change. Regional integration and community building from the grassroots rather than the state level may bypass the risk of perceived interference. With climate action and political change increasingly necessary, there must be another way.

Andrew Ong is the author of Stalemate: Autonomy and Insurgency on the China-Myanmar Border (Cornell University Press, 2023). Minh Bui Jones is publisher at Bui Jones Books.