How to Leave the House of Lords

Members of the House of Lords are traditionally prohibited from giving up their seats. What if a move to the Commons becomes a political necessity?

Appointments to the House of Lords have long been a sore on the British body politic. In 1922 David Lloyd George was exposed for egregiously selling peerages in exchange for donations to the Liberal Party. The Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act followed in 1925, but the banning of such overtly corrupt practices didn’t restore complete confidence in appointments. A century later, Boris Johnson’s resignation honours list and the peers it created (or, in several cases, did not create) sparked another bout of introspection about who is worthy of a place on the red benches.

For a brief period 60 years ago, this perennial controversy was almost completely turned on its head as politicians obsessed less about who was joining the House of Lords than who was trying to get out of it. The trigger for these events was the resignation of Harold Macmillan as prime minister in October 1963. News of his resignation fired the starting gun on the most dramatic internal battle for the premiership in modern history. Over the course of ten days, Conservative MPs, peers and activists jostled to get their preferred man into Number 10. It soon became clear that there were four principal candidates: deputy prime minister Rab Butler, lord president of the council Viscount Hailsham (Quintin Hogg), chancellor of the exchequer Reginald Maudling and foreign secretary the Earl of Home (Alec Douglas-Home).

Peer pressure

Two of the candidates were not like the others: Hogg and Douglas-Home were both hereditary peers. The availability of peers to become prime minister was unusual as it was no longer deemed possible for a member of the House of Lords to be prime minister. As peers could not also sit in the Commons – and as their titles could not be surrendered – it had appeared that the path to the zenith of British political power for a member of the House of Lords was closed.

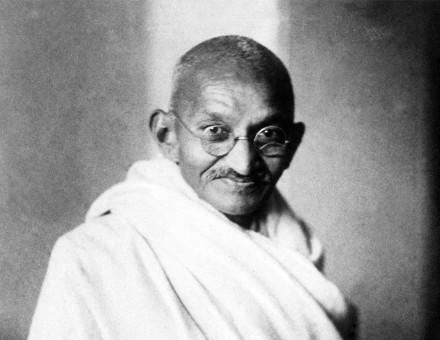

But Hogg and Douglas-Home were able to run, and they had the socialist firebrand and Labour MP Tony Benn to thank for their inclusion among the runners and riders. When his father, the first Viscount Stansgate, died in 1960, Benn declined to resign from the Commons to take his hereditary seat among the peers. Instead, ejected from his place in the Commons, he spent several years campaigning for the right not to be a peer. Benn’s arguments were judged irresistible and on 31 July 1963 the Peerage Act became law. The Act enabled would-be peers in Benn’s position to renounce their peerages prior to taking their seats in the House of Lords. It also established a 12-month window for existing hereditary peers to disclaim their titles. Thanks to this provision, Hogg and Douglas-Home were both in contention to become prime minister.

Hogg moves first

In 1963, the Conservative Party had no formal rules for the election of its leader. Instead, the leader would be whoever the queen appointed as prime minister following advice. Rather than winning the votes of MPs or members, the aim of the would-be premiers was to be seen as having sufficient support to command the confidence of the party, both in the Commons and in the country.

Quintin Hogg was the first to show his hand. He was one of the party’s stars, beloved of the grassroots membership who fondly remembered his time as party chairman (1957-59) and admired the passion and zeal with which he made the Conservative case. The Conservative Party conference, meeting in Blackpool as Macmillan’s resignation was announced, was the ideal moment for the ambitious peer to stake his claim to the premiership. He decided to use the conference to announce he would be leaving the Lords and seeking election to the Commons. He did not explicitly say he was in the running to be prime minister, but the audience knew what he meant and their response was euphoric: members were ‘standing, cheering and waving’. But Hogg was appealing to the wrong crowd. Further up the party hierarchy, where the next prime minister would be chosen, his behaviour was met with a mixture of horror and embarrassment.

Over the following week it became clear that Hogg lacked the support to move into Number 10. But what to do about the peerage? He had made a public pledge to surrender it, but with the premiership out of the question a seat in the Commons no longer came with any great advantage. Switching to the green benches would mean surrendering his father’s title for nothing. In a draft letter to Elizabeth II, Hogg described his father’s viscountcy as ‘the honourable memorial of a good man’s service’. He could not give it up without ‘acute pain’, he wrote, yet he feared that reversing his pledge would confirm, as was surely in fact the case, that he ‘had only announced [his] intention of disclaimer out of [self-] interested motives’. He resolved to stick to his word.

If Hogg could not keep his father’s title, he could at least stand in his former constituency. Douglas Hogg, the first Viscount Hailsham, had been MP for St Marylebone from 1922-28. Four decades later the path was cleared for his son to represent the same seat when Wavell Wakefield, the constituency’s MP since 1945, was elevated to the Lords and a by-election called. Hogg secured the Conservative candidacy and took his place in a contest he later recalled as ‘squalid and painful’. Its nadir came when Hogg’s Liberal opponent accused him of assault, a charge subsequently withdrawn before voters went to the polls.

Seating Douglas-Home

Throughout the battle for the Conservative leadership Alec Douglas-Home played a much wilier game. The popular and affable foreign secretary never overtly bid for the leadership, instead playing the part of the reluctant peer to perfection. He won Macmillan’s confidence and, upon the outgoing prime minister’s recommendation, was invited by the queen to take up residence in Number 10. As he walked through the famous black door for the first time as prime minister, he was still the Earl of Home. A Commons seat would need to be found.

Douglas-Home had his eyes on the constituency of Kinross and West Perthshire. The seat had become vacant in August when Gilmour Leburn, MP since 1955, died. It seemed a perfect fit for Douglas-Home: Scottish, vacant and in the hands of the Conservative & Unionist Party since 1923. There was only one problem: the party had already selected George Younger as its candidate. Sir John George, chairman of the party in Scotland, took Younger to one side and told him: ‘George, you’ll do your duty for your country and your party.’ The ambitious candidate agreed to stand down. (He would later be selected for Ayr and would represent the seat from 1964 to 1992.)

On 23 October, at the height of the by-election campaign, Douglas-Home disclaimed his seat in the House of Lords. So old and prestigious was his family’s claim to a place in the upper house that he in fact had to disclaim six seemingly similar, but distinct, peerages: the Earldom of Home and the Lordships of Dunglass, Home and Hume, all in the peerage of Scotland; the Barony of Hume in the peerage of England; and the barony of Douglas in the peerage of the United Kingdom. For the next fortnight, the prime minister would be a member of neither house, but he was now eligible for election to the Commons.

Life after Lords

Kinross and West Perthshire was, on paper, a safe seat for Douglas-Home and so it proved. After several weeks in which the constituency was turned into an ‘unprecedented circus’ by journalists, no doubt hoping for a surprise upset, the voters showed any Tory worries were misplaced. Douglas-Home won with a comfortable majority of 9,328.

Hogg’s by-election followed a month later and, despite a significant swing against the government, two of Britain’s newest commoners – Mr Hogg and Sir Alec – took their places in the Commons. Douglas-Home served as prime minister until the Conservative defeat in the 1964 election, with Hogg in his cabinet. After relatively short stints in the Commons, both men returned to the Lords as life peers. Hogg did so at the 1970 election to become Lord Hailsham of St Marylebone; in October 1974, Douglas-Home followed as Lord Home of the Hirsel. For Douglas-Home, his return to the Lords marked his effective retirement from frontline politics while Hogg would go on to serve as lord chancellor in the first two Thatcher administrations.

No going back?

The House of Lords has changed dramatically since the 1960s. Most notably, the House of Lords Act of 1999 ended the right of all but 92 hereditary peers to sit on the red benches. Life peers, who now dominate the chamber, have traditionally been prohibited from resigning from the House. And so it appeared all but certain that nobody would repeat the journey made by Hogg and Douglas-Home 60 years ago from active peer to member of the Commons. However, in 2014 the rules were changed again. The House of Lords Reform Act enables life peers to resign and in May 2023 the Daily Telegraph reported that Lord Frost, the former Brexit minister, was considering exercising this right if he is selected as a parliamentary candidate for the next election. Should he do so it will likely cause some controversy – but as the careers of Hogg and Douglas-Home show, it would not be the first time.

Lee David Evans is the John Ramsden Fellow at the Mile End Institute, Queen Mary, University of London.