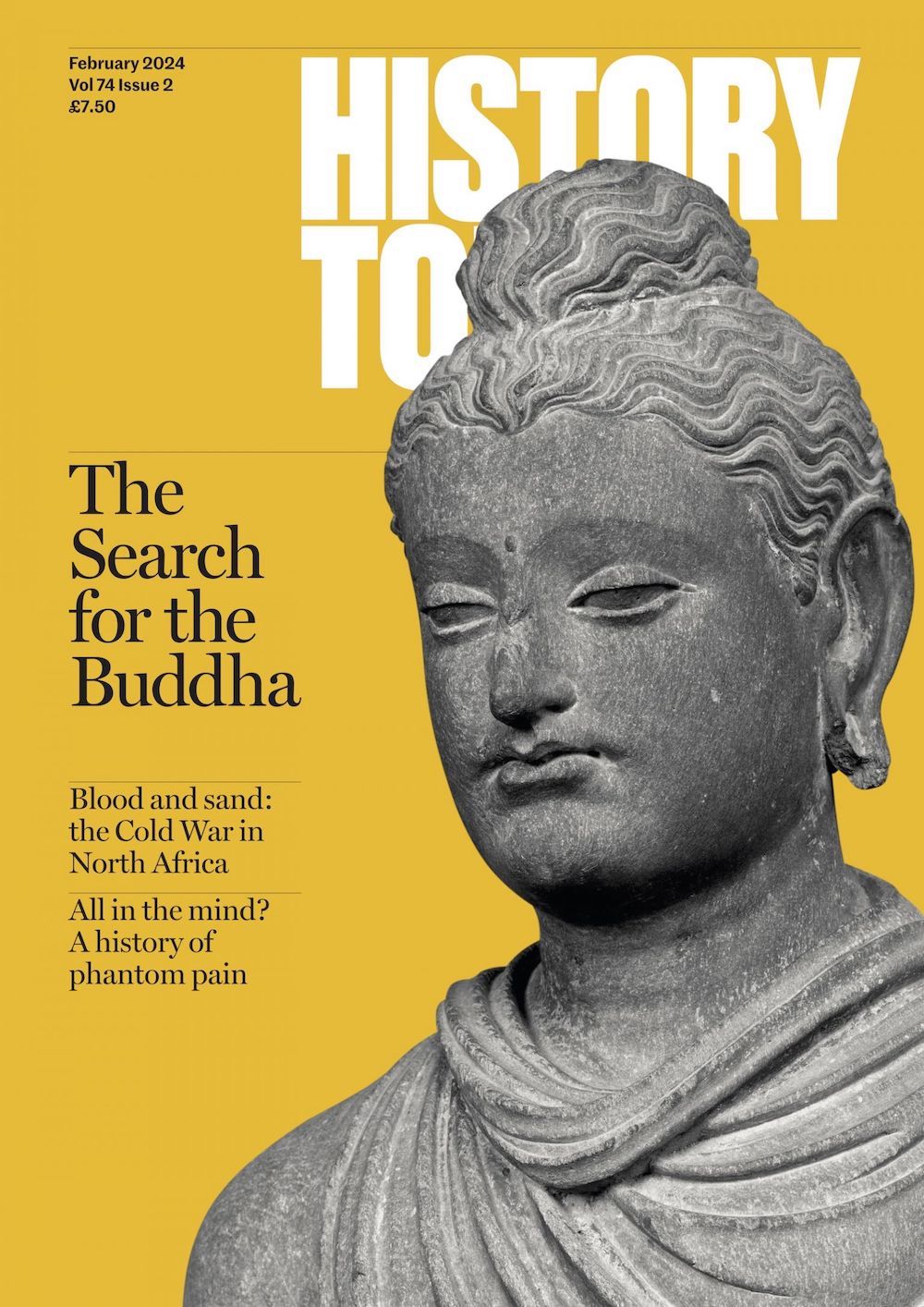

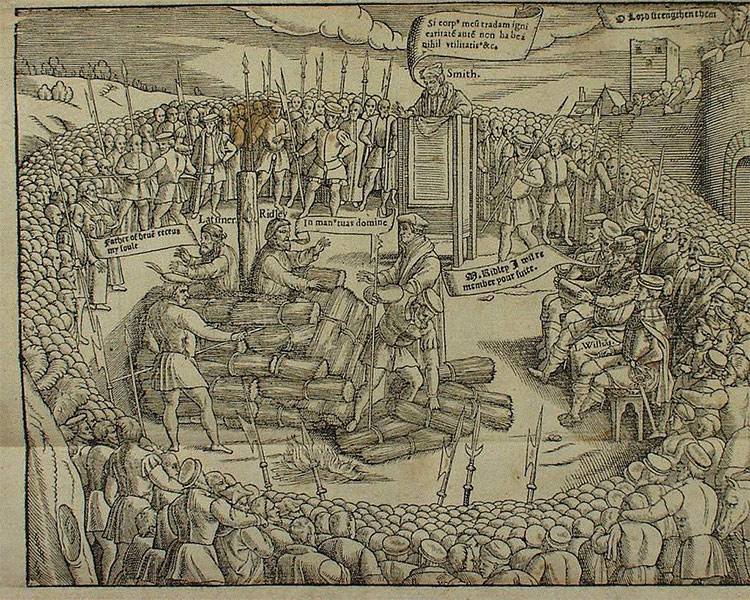

Latimer and Ridley Burned at the Stake

The Oxford Martyrs were killed on 16 October 1555.

Latimer Ridley Foxe burningA cross in the road in Oxford’s Broad St marks the site of the execution. Workmen had discovered part of a stake and some bits of charred bone there, in what had once been part of the town ditch. Whether, as the flames were kindled, Latimer really said, ‘Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man; we shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England as shall never be put out’ is uncertain. The remark, if Latimer made it, came ultimately from the account of the martyrdom of Polycarp in the second century given by the historian Eusebius, an author he knew well. It was in the 1583 edition of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, but not in the earlier edition of 1563. John Foxe was unusual among intellectuals at the time in thinking that burning people to death for their opinions was not an altogether commendable idea.

Latimer Ridley Foxe burningA cross in the road in Oxford’s Broad St marks the site of the execution. Workmen had discovered part of a stake and some bits of charred bone there, in what had once been part of the town ditch. Whether, as the flames were kindled, Latimer really said, ‘Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man; we shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England as shall never be put out’ is uncertain. The remark, if Latimer made it, came ultimately from the account of the martyrdom of Polycarp in the second century given by the historian Eusebius, an author he knew well. It was in the 1583 edition of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, but not in the earlier edition of 1563. John Foxe was unusual among intellectuals at the time in thinking that burning people to death for their opinions was not an altogether commendable idea.

Hugh Latimer was about seventy when he went to the stake. A former Bishop of Worcester, he was later an influential preacher and chaplain in London and at Edward VI’s court. Nicholas Ridley, in his early fifties, had been Bishop of London and an outspoken supporter of the attempt to make Lady Jane Grey queen instead of ‘Bloody’ Mary. After Mary’s accession he was arrested for treason. Latimer was warned that his arrest was imminent, and the new regime might have preferred him to flee abroad, but he stood his ground. From early in 1554 he and Ridley shared a cell in the Tower of London with Archbishop Cranmer and the well-known preacher John Bradford.

In March Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley were moved to the town prison in Oxford, where they were to debate in public with Roman Catholic theologians. Ridley defended his beliefs with particular brilliance and Latimer dismissed his opponents as ‘mass-mongers’. Back in the town gaol, with his faithful servant Augustine Bernher in attendance, Latimer read the New Testament over and over again. No other books were allowed him. Cast down by the mounting defections from Protestant ranks, the prisoners watched anxiously as the heresy trials began in January 1555 and greeted the first burning, of John Rogers at Smithfield in February, as a triumph. Ridley wrote, ‘And yet again I bless God in our dear brother and of this time proto-martyr Rogers.’

The arch-conservative Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and Lord Chancellor, presided over the trial for heresy at the end of September, when Latimer took the opportunity to deliver a blistering attack on the see of Rome as the enemy and persecutor of Christ’s true flock. There was never any doubt about the verdict.

Ridley went to the pyre in a smart black gown, but the grey-haired Latimer, who had a gift for publicity, wore a shabby old garment, which he took off to reveal a shroud. Ridley kissed the stake and both men knelt and prayed. After a fifteen-minute sermon urging them to repent, they were chained to the stake and a bag of gunpowder was hung round each man’s neck. The pyre was made of gorse branches and faggots of wood. As the fire took hold, Latimer was stifled by the smoke and died without pain, but poor Ridley was not so lucky. The wood was piled up above his head, but he writhed in agony and repeatedly cried out, ‘Lord, have mercy upon me’ and ‘I cannot burn’. Cranmer, who was made to watch, would go to his own death the following year.