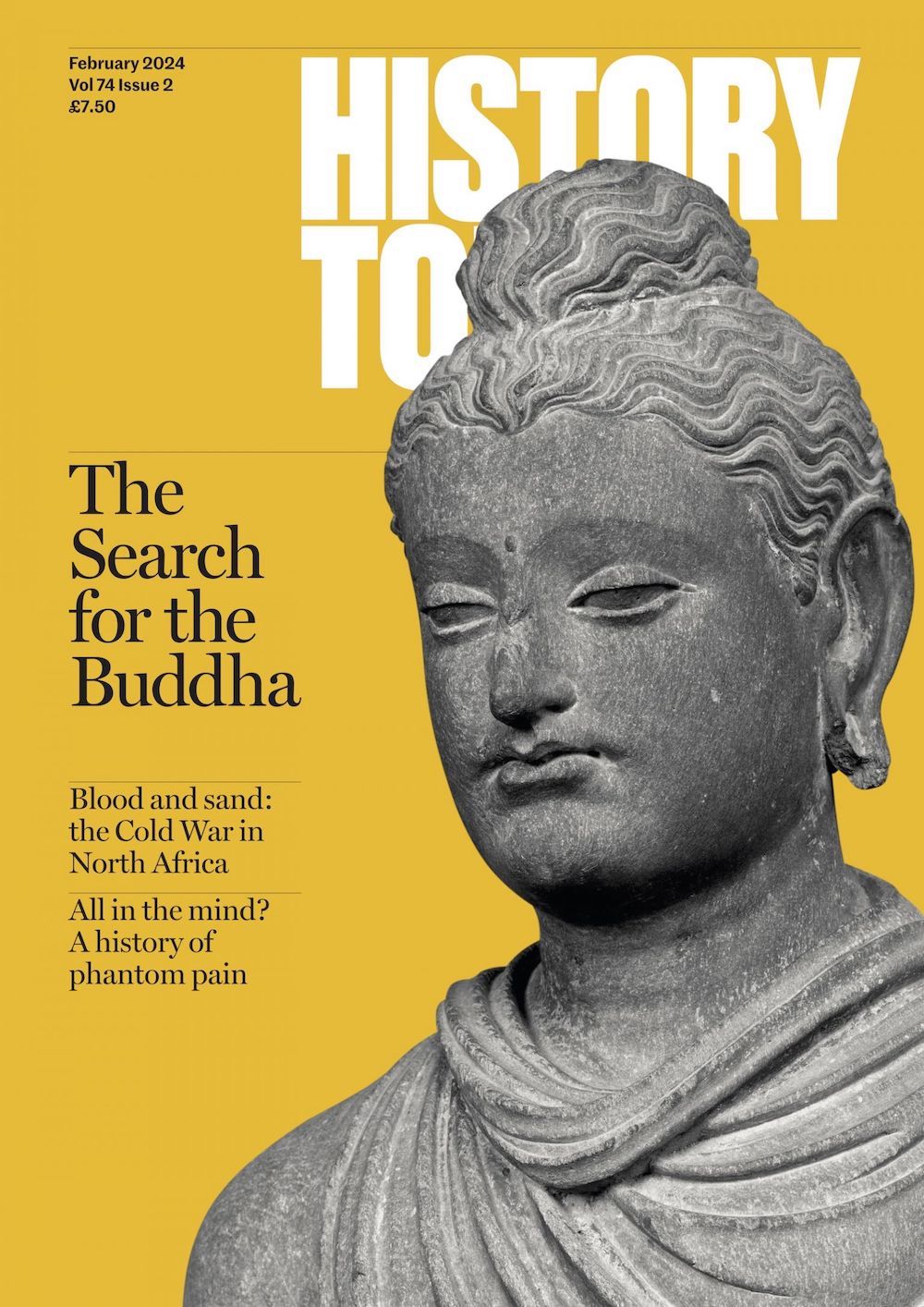

‘Love in a Time of Hate’ by Florian Illies review

An account of the sex lives of European intellectuals is full of gossip – and as shallow as the society pages.

Florian Illies’ new book is full of gossip. Did you know that Simone de Beauvoir stood Jean-Paul Sartre up on their first date, instructing her sister to go to the café and deliver her apologies to someone who was short, bespectacled, and ‘very ugly’? Or that Lion and Marta Feuchtwanger had a very open marriage? Or that F. Scott Fitzgerald showed his penis to Ernest Hemingway in a Paris bar because Zelda had said it was too small? These are the kinds of tidbits that readers are treated to in Love in a Time of Hate. A long-time columnist and editor in Germany, Illies is best known to anglophone readers for 1913: The Year Before the Storm, which interwove snapshots of life from various members of (Western) Europe’s intellectual scene in that final prewar year.

With Love in a Time of Hate, Illies applies that work’s fragmentary style – and the same bemused, quippy columnist’s tone – to a much longer timespan (1929-39) and a clearer thematic focus: sex and romance. Opening with Jean-Paul Sartre waiting, in vain, for Simone de Beauvoir to show up to their first date, the book presents a cleverly arranged series of prose miniatures, each of which is narrated in an immersive, novelistic style and occasionally accompanied by editorial commentary. Some of the book’s nearly 50 characters show up frequently – the Mann family, Anaïs Nin, Pablo Picasso – while others make a few appearances. In running through the private (and not so private) love lives of these figures, Illies quotes freely from diaries, letters and memoirs. He is otherwise light on citation, preferring instead to conjure scenes and anecdotes heavily laden with intrigue, pathos, or both. Some of these fragments succeed on literary grounds, as when Picasso paints his wife, who is furious at him for his infidelity:

And so, on 5 May 1929, Picasso agrees to paint Olga again. Whereas posing for a portrait was once a game between the two of them, a wrestling match, an erotic trial of strength, now it is a cold war. Neither of them says a word. Picasso stares at her and paints. In her nakedness she no longer feels admired but exposed. She sits on her chair, freezing.

As Illies moves through time, a wide array of different narrative threads are picked up, discarded and interwoven. We see Ludwig Wittgenstein’s two failed attempts to overcome his repressedness and initiate a love affair; we meet the ‘New Woman’ of 1920s Berlin via the sexual and social escapades of that generation’s it-girl, Ruth Landshoff. We learn about gay, straight and bisexual romances and we see celebrated authors like Kurt Tucholsky through the eyes of their mistreated former lovers.

The book has three sections: ‘Before’, ‘1933’ and ‘After’. With the Nazis’ ascent to power in 1933, the tone of the book darkens, as the onset of fascism increasingly forces its various protagonists – and their various amorous constellations – to make difficult decisions about conformity, resistance and emigration. Yet the ‘love’ and the ‘time of hate’ in Illies’ title do not meaningfully interact anywhere in the book beyond a general atmosphere of oncoming doom and a few sly revelations about Leni Riefenstahl’s predilection for young beaux working on her film sets. Revealingly, the Nazi takeover and the outbreak of the Second World War is often described in terms of the weather: at one stage the ‘clouds of fascism gather and begin to obscure the sky’. The book’s inability to connect its individual anecdotes of celebrity romance to the broader social and political picture becomes overwhelmingly clear in one of the book’s oddest moments, on Joseph Stalin: ‘The humiliation he feels after his wife’s suicide destroys the last vestiges of humanity inside him. From 9 November 1932 onwards he sees everyone as a plotter to be eradicated.’ Which is one way of accounting for the Great Terror, but not one that holds much analytical water.

Love in a Time of Hate is generally short on both rigour and insight. Illies’ highly novelistic approach has its narrative advantages, but it also blurs the boundary between what is being imagined with artistic licence – a character’s inner monologue or the weather on a certain day – and what is known. Sometimes speculation is presented with the confidence of fact: the Reichstag Fire being a ‘false-flag’ operation, for example, or the homosexuality of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. The book appears to have fallen in the cracks between the genres of pop history, ‘fact novel’ (à la Benjamín Labatut) and historical fiction. Illies, for all his prying, seems to have discovered little about his subjects that is novel or surprising. The juiciest scoops appear to be that Bertolt Brecht and Pablo Picasso were bad husbands; that Jean-Paul Sartre was jealous and vain; that Thomas Mann was an icy, unsympathetic father; and that sometimes great thinkers don’t always live up to their ideas in real life. Well then!

Illies’ quippy narration relies, throughout, on heavily clichéd psychological interpretations of both individual figures – that Thomas Mann was cruel to his son, Klaus, because he envied Klaus being openly gay – and of the era as a whole: ‘No one in 1929 has yet invested any hope in the future, and no one wishes to be reminded of the past’, he writes at the beginning of one section. ‘This is why everyone is so recklessly absorbed in the present.’ It also, like most gossip, holds its subjects in contempt: one of Illies’ favourite constructions is to note that a particular person ‘does not yet know’ that the oncoming war will have this or that consequence – an invitation for readers to ironise his disoriented literati while luxuriating in the easy condescension of the present.

Ultimately, the book’s inability to transcend gossip represents a missed opportunity. The love lives of interwar Western Europe’s intellectual elites need not be a superficial topic – not least because many of these figures were themselves dedicated to exploring romance, sexuality, affection and the thorny relationship between commitment and freedom. Yet in Illies’ account, the actual substance of these figures’ art and thought is almost entirely absent. This is particularly galling in the case of Simone de Beauvoir, who appears in this book more as a suffering girlfriend than as one of the century’s most influential philosophers of sexuality and love. Illies’ German subtitle, Chronik eines Gefühls (‘Chronicle of a Feeling’), is therefore both misleading and frustrating. Neither a history-of-emotions in the manner of Barbara Rosenwein, nor a contribution to what the Germans call Begriffsgeschichte – the history of concepts – the book gives readers no sense of what these figures mean when they say or feel ‘love’. The book offers no insight into what should be its central question: why – intellectually or socially – did this generation of cultural elites find themselves so drawn both to marriage and to sexual liberty? In the absence of such analysis, readers are left with a movie-montage of superficial anecdotes about one specific – and, of course, spectacularly un-generalisable – set of people.

Illies’ wisecracking wunderkammer does not take seriously either 20th-century creativity or the rise of fascism. Both, instead, serve only to add glamour and gravitas to an essentially gossiping enterprise. The result is enjoyable enough to read, and rather skilfully composed. But then so are the society pages. Still, this book also has the virtue of gossip, in that its saucy anecdotes might provoke curiosity and inspire anglophone readers to look further into the life and work of figures such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Mascha Kaléko or Erich Kästner.

Love in a Time of Hate: Art and Passion in the Shadow of War, 1929-39

Florian Illies, translated by Simon Pare

Profile, 336pp, £20

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Alexander Wells is a writer based in Berlin.