Why Were the Jews Persecuted?

Tim Black seeks to understand the origins of antisemitism, looking beyond the Holocaust to the ancient Middle East and medieval Europe.

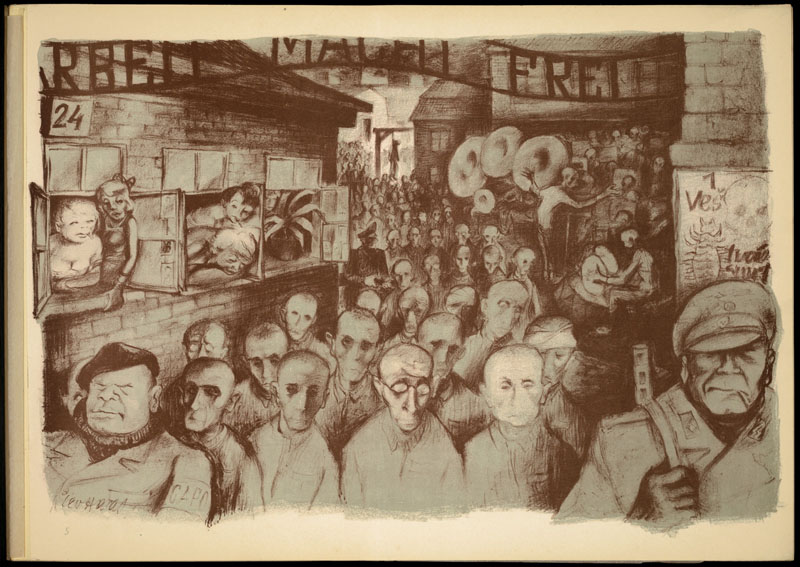

Throughout the history of mankind, no group has been more victimised than the Jewish people. Today they are remembered for being mass-murdered in Hitler's death camps, yet their persecution goes back thousands of years. Why? In order to understand how Hitler was to use the Jews as scapegoats, we must first understand the latent hatred that Hitler was able to tap into against the Jewish people, not just in Germany but all over Europe.

Biblical Times

Much of the history of the Jewish people can be found in the Old Testament, in which we learn that the Jews are the 'chosen people'. By making a covenant with God, they would, in return for being chosen, obey his laws. After their exile in Egypt the Jewish people were led back by Moses into Israel, where, by force of arms, they were able to carve out a land of their own around 1100 BC.

In the century before the birth of Christ, the Middle East and Judea were conquered by the Romans under Pompey and became part of the Roman Empire. From the New Testament, Christians learn how the Romans governed Judea, and it is under Pilate's orders - and amid Jewish cries of 'Crucify him!' - that Jesus was executed. The Romans found the Jews with their one god to be a troublesome people. They would not allow Roman gods to be worshipped in their temples even though the Romans (although not always) respected the God of the Jews.

Unrest broke out and the Romans put down the disturbances ruthlessly. After the fall of Masada, Jewish resistance was broken and the Romans expelled the Jews from Judea in AD 135 (the Diaspora). At this point we would expect the Jews to leave history in the manner of the other ancient civilisations, such as the Babylonians and the Hittites; but no, the Jewish people survived even though they were dispersed throughout the Roman Empire and beyond. If we understand why, we also begin to understand the persecution that followed.

Read Next: The Roman Destruction of Jerusalem

Keeping the Faith

The contract with God bound the Jewish people together: if they kept his rules, then, whatever else happened, they would remain his chosen people. This belief gave a sense of faith and identity which was to hold the Jewish people together but also to alienate them from other cultures. The strict rules that had to be followed did not always match with the rules of the different societies in which the Jews now lived. They had, as far as possible, to reduce their contact with the outside society so that it would be easier to keep their own laws. Keeping themselves apart was the main way in which the Jewish people would survive, yet it was also the main factor in their persecution. As visible outsiders, they were seen to be aloof, strange, exotic - and even evil.

If the Jewish faith had been one of conversion like the Christian or Muslim religions, then it would have been a direct threat to other societies and the Jewish faith would have either triumphed or been vanquished. Yet neither occurred. Being Jewish depended on being born into the religion, and the Jews would only take converts very reluctantly into their faith.

Being outsiders was bad enough, but having power as well represented a threat to the upper levels of the societies in which they were living. Unlike the Christian faith in its early days where the word of God was given to the people by their priests, who were often the only group of people who could read, all Jewish males were required to be literate in order to read the Torah and to debate its contents. Two factors are important: one, the ability to read, which in the Dark Ages and Middle Ages was rare; second, not to accept blindly what was read but to interrupt and debate. This meant that the Jewish people were a literate society which encouraged the art of debate and the search for knowledge.

The Rewards

It was no wonder, then, that the Jewish people were to provide society's professional classes, including doctors, lawyers, advisers and bankers. In societies before the modern age, wealth was land and its ownership. Landowners did not 'work', since they ruled and also fought as soldiers. The Jews had no land and were often banned by the societies they were living in from owning land. Yet they had the skills which the landed classes wanted but were unwilling to acquire themselves: 'labourers' and 'cannon fodder' the ruling classes had in plenty, but of doctors there were few.

The Jews were paid for their services in cash but with this cash they often could not purchase land, and so they ended up with the capital required to run money-lending firms and banks. This factor, combined with the Christian ban on usury, meant that Jews were often forced to act as their adopted society's bankers.

From this we can see that the Jews were an independent people who lived all over the known world and who cut themselves off from the indigenous people of the area in which they lived; but at the same time they provided essential services for those same indigenous people. This gave the Jews power that could be abused or that could seem threatening to the local population. However, power was also a defence for the Jewish society against possible persecution.

The Jews, in addition to having money and power, also had knowledge. In a time when there was little movement of people or ideas, the Jews were unique. All over the known world there were Jewish settlements, and in all these societies the Jewish people learnt both the language of the local people and their knowledge and wisdom. This knowledge was then dispersed among the Jewish people through their travels and, of course, through books which the Jews could read. Ideas spread but stayed within the Jewish community. So a Jewish doctor might cure a patient in Scotland with knowledge gained from Syria. However, again there was a danger, for what was common sense in Syria might be perceived as 'Black Magic' in Scotland.

Read Next: Jews and the Renaissance

Persecution

The first persecutions against the Jewish people were religious. They were 'killers of Christ' and 'black magic worshippers' who did not follow or believe in Jesus. We can see that hatred was felt by the local populations; but it was the leaders of the different societies which stirred up that hate, and their reasons for doing so could be mixed. Among the ring-leaders might be a zealot Christian church leader, a knight in debt to a Jewish money-lender, a jealous doctor or a usurped advisor to a king.

In the 19th century religious persecution gave way to racial persecution. The Jews were seen as parasites. This change in attitude came from a volatile brew of Social Darwinism and rising European nationalism. The Jews were seen to be the outsiders who not only did not belong but needed to be removed as a threat to society. This is the sort of emotion Hitler experienced when living in old Imperial Vienna before 1914.

More sinister, in both cases, religious and racial persecution are a facade for the real reason that the Jews were seen as threatening, namely the fear and threat from an outside group who through history had a position of power that created jealously which turned to violence in troubled times.

In the 20th century another factor for persecution can be added, and this is the Jewish connection to Communism. In 1897 in Basel, the first Zionist conference was held. Theodore Herzl, the father of Zionism, talked of sending Jews to Palestine to build a homeland. The Zionist thinkers talked of a society which was less class-driven - Socialism. In 1917 the Russian revolution took place and, among its leaders, Trotsky was Jewish. Trotsky believed in a world revolution, and his call was first answered in Germany, where many of the leaders in the 'Munich Soviet' of 1918-19 were Jewish. Thus the greatest radical idea of the 20th century was to be linked to Jewish thinkers. In Nazi Germany, Social Darwinism, Communism, Socialism and war-profiteering were to be mixed and brewed to become the hatred that Hitler stirred up from the 1920s to the 1940s.

Conclusion

Anti-Semitism was not a creation of Hitler. It has been part of European society for over 2000 years. The Jewish religion and the attempt to maintain it, when the Jews were expelled from their homeland by the Romans, was the key factor in their survival as a group; but by being a recognisable group who had power they seemed to threaten many of their adopted societies.

The fate of the Jews is the fate of all minorities the world over. They are accepted when they are not a danger to their adopted society, but turned on whenever they might appear threatening. The murder of the Jews in the Holocaust remains a 'beacon of remembrance' of what society can do when it turns on a group of its citizens.

Hitler tapped into the tendency that lies in all individuals to blame those who-are 'not like us' in times of troubles. Though there may be elements of truth behind our blame and hatred, the issues are far more complex than the 'black-and-white' world Hitler and his like want people to believe in. We do not hate an individual for his racial affiliation or belief, but we are made to hate a stereotype which we often have never met.

Further Reading:

- N. Cantor and R. Waddington, The Sacred Chain - A History of the Jews: The Expulsion of the Jews - 1492 and after (HarperCollins, 1995)

- A. Farmer, Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust (Hodder & Stoughton, 1998)

- N Faulkner, 'Apocalypse: The Great Jewish Revolt against Rome,

66-73CE', History Today, October 2002. - R. Ovendale, The Origins of The Arab-Israeli Wars (Longman, 1999)