‘With Her Own Hair’: A Victorian Prisoner’s Art

Arrested over 400 times, Annie Parker found redemption in intricate cross-stitch and crochet using her own hair.

A Deptford woman named Annie Parker sat in a dank, cold cell in Kent’s Maidstone Gaol in 1879. Jailed for drunkenness, this was not her first time behind prison bars; of the past 365 days she had spent 350 in prison and, by the time of her death six years later, had been arrested for drunkenness and other associated crimes more than 400 times. Sitting in her cell, she cross-stitched on bleached linen. It was not thread she stitched with, but her own hair.

Born around 1847 in an unknown location and to unknown parents (though in a 27 January 1872 edition of the Woolwich Gazette she said she had no father and a ‘bad’ mother), Annie Parker spent years of her life in Maidstone or Bedford Gaol for drunkenness. It seems that she first began getting arrested frequently around 1871; by January 1872, she had been in custody 20 times in 12 months. Despite being married, by 1877 she had no fixed home. She is listed in a Greenwich workhouse record that year as having no occupation, no home, and no friends, though contemporary newspaper articles claim she would leave prison and be met with acquaintances offering her alcohol. Some of her behaviour was violent, breaking windows and committing robbery, while other crimes included attempting suicide, which saw her sentenced to two years’ hard labour. Though released four months early on the condition that she would emigrate to America, Parker stayed for just one week before returning to England.

In life and death, Annie Parker was famed for her hairwork embroidery. On 23 June 1882 The Kentish Mercury recalled that: ‘As an instance of the cleverness of some of the prisoners that came under his notice Mr. Horsley [the Reverend Horsley, chaplain of the Clerkenwell House of Detention] showed some crochet work made with hair by Annie Parker (well known in Deptford)’. The Illustrated Police News published the following in their 29 August 1885 memorial, following Parker’s death at 38:

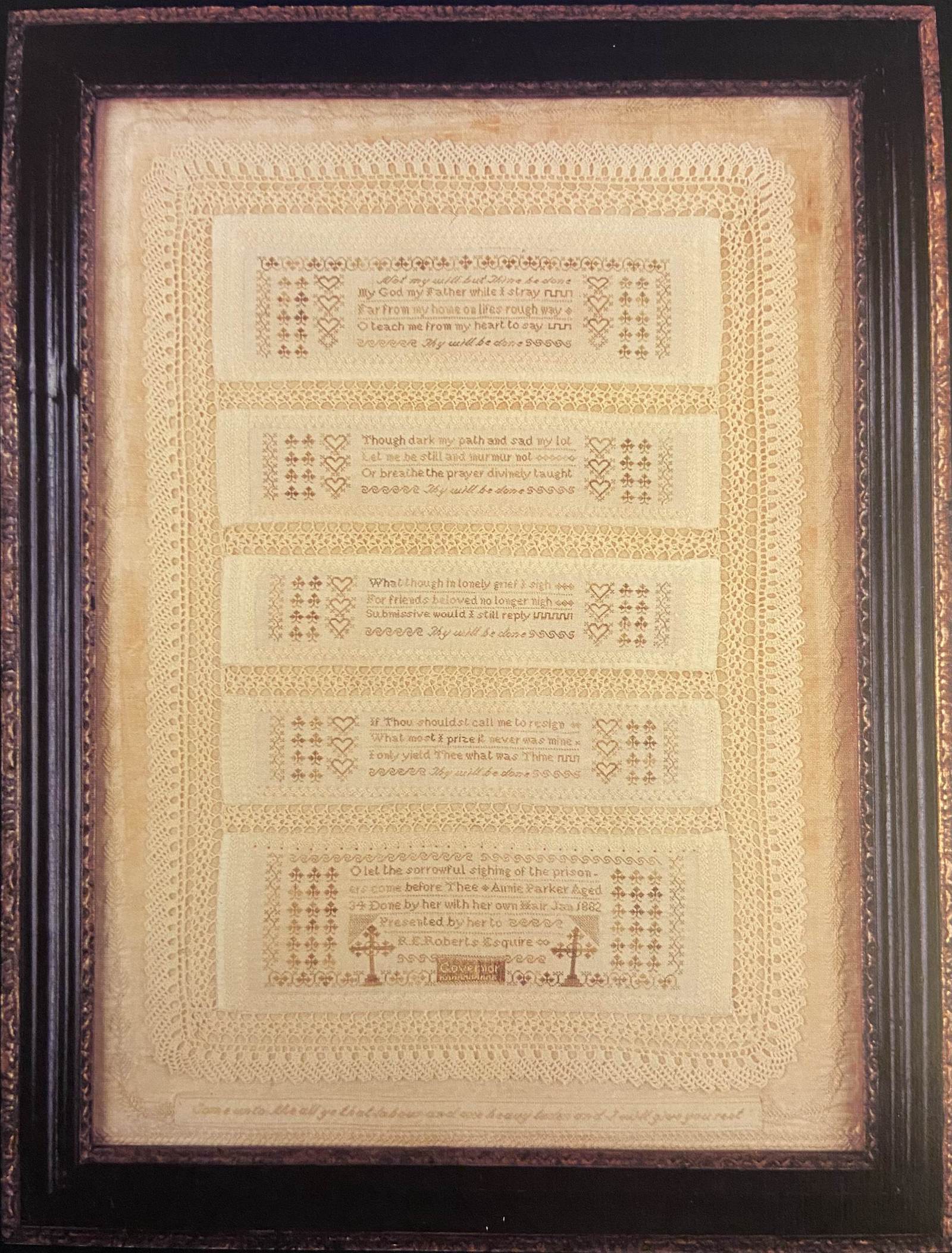

‘She had a luxuriant head of hair, and on the morning of her death presented to Dr Dixon, the assistant medical officer of the infirmary, a lace-bordered sampler … Another beautiful specimen of her hair work is in the possession of the Rev JW Horsley … and a third is framed in the parlour of Mr James.’

Parker embroidered on linen using cross stitches made of her brown hair with the occasional stitch worked in red, light green, or brown thread – though there is no indication of how exactly she obtained her linen, needles, crochet hooks or thread. The earliest known examples of her hairwork dates to 1879 and the latest to 1882. They are held by the City of London Police Museum, National Justice Museum and several private collections. Half were formerly or are currently in the collection of Witney Antiques in Oxfordshire.

At least six of Parker’s hairwork pieces survive, five of them samplers and one a pin cushion. The samplers’ linen is longer than it is wide, rectangles approximately a foot and a half in length. Often, she crocheted all four edges and the space in between the verses. Parker stitched religious verses and was evidently especially fond of the hymns of Charlotte Elliott (1789-1871), embroidering Elliott’s hymn ‘My God, My Father, While I Stray’ several times, stitching verses such as ‘Though dark my path and sad my lot/Let me be still and murmur not/Or breathe the prayer divinely taught/Thy will be done’ and ‘What though in lonely grief I sigh/For friends beloved no longer nigh/Submissive would I still reply/Thy will be done’. Parker’s choice of verse suggests she used embroidery to atone, grieve and seek absolution through the slow, painful work of plucking out her hair and transforming it into tiny stitches. She often concluded her embroidered verse looking heavenward, finishing off the rhyming hymns with sentiments such as ‘Thy home is in Heaven’ or ‘Thy reward is in heaven’. The piety present in her embroidery is also exhibited in her appearances in the historical record, where she speaks of her faith and God’s goodness with quotes like: ‘The Almighty is good to me, if other people ain’t’, which she was recorded as saying in the 22 December 1883 issue of the Sydenham and Penge Gazette. Religion offered her solace in the jail cell, in the workhouse, and on the streets where she spent the last years of her life.

Parker’s earliest piece of hairwork may be one that concludes, ‘Come unto me all ye that labour and/are heavy laden and I will give you rest/Annie Parker/Done by her in/fond memory of Thomas Parker/Who died Jan 6 79’. Research suggests that Thomas Parker, who was buried in the churchyard of St Paul’s Deptford on 13 January 1879, was Annie Parker’s husband. He does not appear in the written record as often as his wife, and when he does he is listed as having any number of jobs. When he died aged 41, he was a stationer. Thomas was described in the 24 August 1872 issue of the Kentish Mercury as ‘a ruffianly-looking fellow’ who was ‘charged with assaulting his wife, Annie Parker’, who was left ‘bleeding from the mouth’, two of her teeth loosened.

Another article from the Kentish Mercury, this one from 20 April 1878, reveals that Annie and Thomas had at least four children, all of whom had been born in Maidstone prison and all of whom had died: ‘Annie Parker, who has been several hundred times in custody for drunkenness … said [to a police constable] she had only come out of Maidstone gaol a week since, and was confined with a child there a week before she was liberated, being her fourth child born in that prison, the whole of whom were dead’. While Annie Parker’s embroidery illustrates that she was pious and repentant, it seems that abuse and loss may have contributed to her addiction. Evidently, the death of her husband was so distressing she took to self-mortification to craft objects that spoke of despair, loneliness and a desperate hope that her afterlife would be better than her time on earth.

Between her hairwork embroideries and her presence in workhouse records and newspapers from Kent, London and further afield, we know significantly more about Annie Parker than we do about many other late 19th-century women. It is clear that Parker had become an object of widespread fascination. But even with this surplus of information, we are left trying to find the ‘real’ Annie Parker, the one not sensationalised in newspapers as a ‘notorious woman’ described as having ‘“a screw loose somewhere,” and it seems […] to have been just where the alcohol goes to’. In print she is mythologised and sensationalised, her agency lost. In stitch we have not only her own words, but also a glimpse into how she expressed her emotions, passed the time, and perhaps found some peace behind prison bars.

When Annie Parker died of consumption in the Greenwich workhouse infirmary in 1885 she was posthumously commemorated for her exceptional conduct in prison and her excellent education, suggesting she may have once had a different life from the one she had on the streets of Deptford and Lewisham. The newspapers that chronicled her many arrests painted her as an infamous drunk; in reality, she was a grieving mother, an abused wife and a victim of a society without the tools or inclination to help her. Annie Parker’s embroidery presents us with a woman repenting and trying to right her wrongs in the most desperate of circumstances – and using her own body to do so.

Isabella Rosner is an art historian specialising in material culture and is the curator of the Royal School of Needlework and research associate at Witney Antiques.